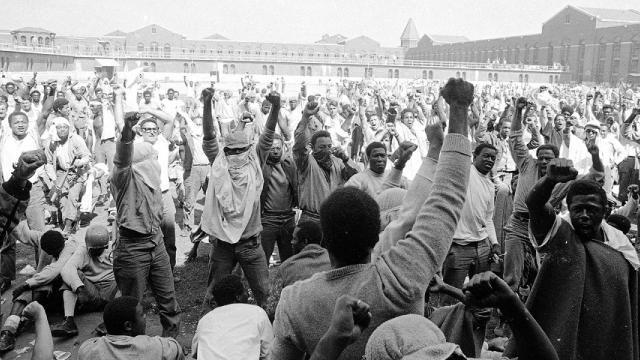

Last month, inmates across the country embarked on what organizers have called the largest prison strike in U.S. history, an ambitious mass protest against prison labor and inhumane prison conditions. The strike, which was the culmination of a series of renewed efforts at prison organizing in recent years, kicked off on September 9, in tribute to one of the bleakest moments in the country’s history of incarceration, the uprising at the Attica Correctional Facility, in upstate New York.

On September 9, 1971, prisoners at the overcrowded prison seized an opportunity to gain control of the facility and took a number of hostages, inspired by earlier prison and jail uprisings and by the momentum of the liberation movements raging outside the prisons’ walls. But prisoners at Attica were mostly driven by growing desperation over unbearable conditions inside: constant abuse by guards, medical neglect, lack of showers and toilet paper. Four people — one guard and three prisoners — were killed in the early hours of the riot. Then for the following four days a group of leaders who emerged out of the initial chaos attempted to negotiate a peaceful surrender with state officials, demanding amnesty for actions conducted during the riot, as well as access to classes, religious freedom, and fairer disciplinary practices.

Despite recommendations from all sides that he do so, New York state governor Nelson Rockefeller — who two years later shaped the future of New York’s criminal justice system when he signed his infamous drug laws — refused to visit Attica. Instead, on September 13, he ordered state troopers to “retake” the prison.

By the end of the assault, 39 people — 29 prisoners and 10 hostages — had been killed by police, who entered the prison protected by a thick fog of tear gas and armed with state-issued weapons as well as personal guns and hunting rifles. Dozens of other inmates were injured and tortured in the hours that followed. But as the state regained control of the prison, officials told reporters waiting outside that prisoners had killed the hostages, sometimes embellishing those accounts with fabricated details that shocked public opinion, like when they said an inmate castrated one of the guards and shoved his testicles into his mouth.

What followed was an enormous cover-up, as 62 prisoners and zero law enforcement officials were indicted over the massacre. The cover-up was partially exposed in the decades that followed, but the magnitude and callousness of it all is something we are just now beginning to fathom thanks to Blood in The Water, a monumental account of the uprising and its aftermath by historian Heather Ann Thompson, published earlier this year.

Thompson’s book documents the Attica violence in painful detail: the circumstances leading up to the uprising and the lengths to which the state went to hide its responsibility in the decades that followed. Thompson makes the case that the Attica massacre, and the lies that Americans were told about it, played a pivotal role in justifying the dehumanization of prisoners and in providing political support for the mass incarceration binge the country embarked in the decades that followed. While Attica continues to inspire resistance among prisoners, the uprising’s most lasting legacy has been one of exacerbated repression, as corrections officials stifled prison dissent and organizing and the general public turned its back to prisoners’ continuing demands for human rights and dignity.

“Even though the extraordinary violence that took place in 1971 was overwhelmingly perpetrated by members of law enforcement, not the prisoners, American voters ultimately did not respond to this prison uprising by demanding that states rein in police power,” Thompson writes in the book. “Instead they demanded that police be given even more support and even more punitive laws to enforce.”

Today, Attica remains a prison, rife with abuse, rather than a monument to a massacre. Prisons nationwide are significantly more crowded today than they were in 1971, and they are often more punitive and less humane. The racial inequality that defined the prison experience then, and that essentially enabled the lynching that was the retaking of Attica, remains a defining factor of prison life and abuse. And today prisoners are once again rebelling, while states go to great lengths to silence them.

As the current prison strike, barely noticed by the public or acknowledged by corrections officials, entered its third week, The Intercept spoke with Thompson about what’s changed in prisons since 1971, and what hasn’t.

One of the running threads in your book is the state’s refusal — to this day — to open the books on Attica and allow the public to know what really happened 45 years ago. But accessing prisons remains incredibly challenging for the public today. Why is it so hard, for instance, to get accurate information on the current strike?

It’s really an outrage. These are public institutions, and not only can the media not get access, but neither can the families of those inside. Neither can state senators — elected officials find it incredibly difficult to get information out of the prison system. It was not my intention to make my book so timely, but if you know anything about Attica you understand that what you don’t know is always much worse than what you might imagine. These prison strikes have been happening for days and corrections officials were denying them. Now corrections officials are reporting that there have been incidents, but we don’t know how many people are involved, we don’t know what the repression is. Frankly, the only reason we know about Attica today is that reporters and law students and lawyers didn’t give up. They just insisted, came back again and again and again, filing injunctions, beating down the doors, insisting that their state legislators come in, and that’s the only reason why we have any idea that basically 1,300 people were tortured as long as they were.

It is unconscionable that prisoners in states across this country are protesting the conditions under which they live and are forced to work and the media cannot be told who they are, how many of them there are, what their demands are, and what the repercussions of their acts have been. The fact that we cannot get any of those questions answered by public institutions is outrageous and unforgivable given the support we give them.

Some prisoners today are trying really hard to reach out to people outside, even to connect to the broader movement for justice that we have seen resurface in recent years. But even when they are able to get their story out, increasingly through social media, there seems to be limited interest in their struggle. Why?

There’s no question that by the time Attica happened we were in the midst of a pretty deep social movement, that lots of young people took time off of their day jobs to tell prisoners’ stories and to demand prisoner justice. But that took a long time — there were prisoner atrocities going on for a very long time in many of these prisons. Martin Sostre had to file a federal suit to stop the solitary confinement he was suffering in Attica long before the uprising. The southern prisons were hell holes, they had nobody paying particular attention.

I think we’re in the beginning of that movement again. I feel like that energy and that interest is starting again. But the fact that we have perhaps more access to prisoners through social media, you have to remember that that is being mitigated against by the fact that prisoners do far more time in solitary than they ever did. They are on lockdown in their cells far more than they ever were, and frankly, the punitive nature of the parole system and the sentencing rules mean that many of them get cut off. They have been away for so long that it’s only a core few who manage to keep their outside networks up.

The Attica uprising came as a movement for prison justice was beginning to take hold. What happened afterward?

The movement didn’t die out at all. However, what happened after 1971 is that the police retook Attica, they did all the killing, they did all the maiming, they did all the torture, but then the state stepped out in front of the nation and said that it was prisoners that killed the hostages. And when they did that, they gave the emotional fuel to this punitive system we have today. They had already started down that path but Attica turned people, the broader nation, against prisoners’ rights. And it made possible shutting down prisoner access to the federal court system, with the Prison Litigation Reform Act, it made possible the amount of solitary confinement that happens today. In the Martin Sostre case, in 1969, a federal judge said it was cruel and inhumane to keep someone in solitary for 365 days. We now hold people in solitary for ten years or longer. Prisons became much more punitive, but that’s not because they managed to shut down resistance, they actually managed to “shut down” the prisoners themselves.

When you write about prisoners’ rights, you invariably will get someone saying, “They’re prisoners, they deserve it.” How do you trace this attitude towards prisoners to what happened at Attica?

At the height of Attica, if you look at public opinion polls, there was quite a notable degree of support for prison reform and for better guard training and more humane conditions in prisons. After Attica, that door closes. The carceral state was a backlash to the civil rights movement, and Attica was the pinnacle of that link between the civil rights movement and the prison rights movement. Today, people are still very hostile to the idea that prisoners are people. But I feel like we’re in a changing moment right now. I don’t want to be too optimistic but I feel like it’s very significant that prisoners are resisting despite enormous odds, higher odds than they faced in 1971. They are going on strike, they are refusing to be warehoused. And I think that the broader public is beginning to understand that these are people we’re talking about.

But prisoners are once again protesting the same conditions they rebelled against in 1971. Or are they worse?

They’re much worse now. They’re much worse because what should have happened after Attica and what was undoubtedly on the way to happening was a humanizing of prison conditions. We were moving towards community corrections. We were moving away from warehousing, and after Attica we reversed that trend in horrifying ways and now the chickens are coming home to roost. And by the way, we’re not waking up because politicians all of a sudden got a conscience. We’re waking up because of Ferguson and Baltimore and Chicago and Charlotte. We’re waking up because people are saying enough and now they’re even saying enough in prisons. I think this moment is a new civil rights era.

Is the current resurgence of prison activism tied to the movement for black lives outside prisons? And how does that compare to the way the Attica uprising came on the heels of the civil rights movement?

If you look at a snapshot of 1970 it looks as if activism for civil rights in the streets and activism in the prisons are all happening simultaneously and people understand the connections. But it took a decade of enormous work and of both prison uprisings and urban rebellions before those connections were made. Today, we know intellectually that you wouldn’t have mass incarceration without excessive policing in black communities, but people erupt where they are. It’s not surprising to me that the first eruptions are going to be in the communities, because that’s exactly where they were in the 1970s. It’s in 1964 that we get rebellions in Philadelphia and Rochester and Harlem, but it’s not until the later 60s and the early 70s that prisons start rising up and that people are mobilizing both communities. I see the fact that we’re having these things just now starting up in prisons as a very interesting sign.

In the immediate aftermath of Attica, the media disastrously failed to see through officials’ lies. Today, with some notable exceptions, prison coverage continues to be limited and lacking, even as the movement for prison reform gains some ground. Why are we not covering prisons more aggressively?

The way that we need to start leaning on the broader media is to say: These are public institutions. We spend an incredible percentage of our tax dollars and give a considerable amount of our good will and faith to institutions we are literally barred from understanding. And those institutions are in charge of our nation’s most vulnerable citizens, the poorest people, the most mentally ill. From a purely investigative journalism point of view, this is a question of access to public information and I feel that it was that spirit that led reporters in the 1960s and 1970s to uncover some of the worst abuses. It wasn’t that they were leftists or radicals, it was that they were journalists and they felt that they had a right to the information. I think that spirit is crucially important and I feel that journalists today have lost much of that; they think the story is what the press office gives them. Your job is not what the press office is giving you, your job is what the press office is not telling you.

Your book was made possible, in part, by the mistake of a courthouse clerk in Buffalo who erroneously gave you access to thousands of pages of documents that the state did not mean for anyone to see — and that have since disappeared. (Officials have even denied that those documents were there in the first place.) What does the fact that it’s so hard to get government to talk about something that happened 45 years ago say about government-perpetrated injustice that continues to go on today?

For one thing it says that every time we have a police shooting the public needs to insist that the grand jury process is more transparent, and that there have to be independent prosecutors, that is to say, prosecutors who never have to rely on the police any other time. Also, Attica was 45 years ago, but there’s no statute of limitations on murder. For many decades it was the very active fear of prosecution that motivated the state’s police unions to show up and to not let the records be disclosed. But I think that everybody understands that this is not old history. These records say something fundamental about race and justice and equal justice under the law, not just in New York but in America. What’s being protected is the legitimacy of the state, the idea — or the fantasy — that politicians are above this ugliness and that state officials do the right thing. What’s being protected goes to the fundamental nature of how society works — if you don’t have legitimacy of government you don’t have anything.

I’m not sure what we can do about the past; we should still push for these records, and frankly there still needs to be a truth and reconciliation process for what happened at Attica. That’s what the survivors want, that’s what they deserve. But what I hope the book does, in addition to rescuing their history, is make all citizens much more cynical, skeptical, curious, and cautious about these days we walk in right now. Because these things are still with us. Attica is not that unusual. Attica is just emblematic of prisons everywhere; there have been uprisings at almost every prison in America. What might be happening right now at Holmes correctional facility in Florida makes me shudder. It just keeps going on and on until we shine a light on it.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments