We’ve written before about the perverse phenomenon known as “zombie title.” Servicers initiate a foreclosure and complete most of the steps, including evicting the borrowers, but then fail to take title to the house. Adding insult to injury, the banks rarely inform the former homeowner of this cynical move. Not only does often find out years later that he’s on the hook for property taxes and in some cases, fines from the local government, but the servicer has made such a mess of title that the owner can’t get rid of the property, unless he takes a quiet title action, which typically can’t commence until five years after the foreclosure was abandoned.

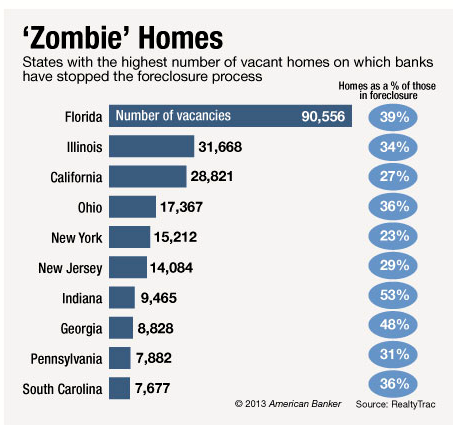

Kate Berry of American Banker provides an update. She flags that this abuse has skyrocketed since 2010, when the GAO estimated that abandoned homes ranged between 14,500 and 35,600. They are now pegged at 35% of the one million homes in foreclosure.

Homeowner advocates are up in arms because both the Fed and OCC have issued guidance requiring servicers to inform borrowers and municipalities if they intend not to complete a foreclosure. They also contend that this is a fair lending practice abuse, since, natch, the borrowers tend to live in low-income communities. And abandoned homes are a blight.

Normal local statues dealing with vacant properties hit the owner, which is the hapless homeowner, not the servicer. This problem is hitting a level where local authorities may start taking more aggressive measures. I’d love to see a “bad faith foreclosure” fine, for parties that evict a homeowner but fail to take title to a property in a stipulated period of time. The fine would need to be punitive, say $10,000, and allow for recovery of costs if the municipality has to take unusual measures to collect (say putting a lien on a local bank branch and then threatening to foreclose).

But there are bigger implications of this sorry trend. The first is that it means the “housing is on a firm footing, look how tight inventories are” story bears some scrutiny. From the article:

"Housing experts speculate that banks are purposely refusing to take title of abandoned foreclosures as a strategic move to better manage their ballooning portfolios of real-estate owned or REO properties. If more properties were put on the market, it might dampen the nascent housing recovery, the thinking goes." “I have long been convinced that the current run up in home prices is a false high,” says Ruhi Maker, a senior staff attorney at the nonprofit Empire Justice Center in Rochester, N.Y. “Once all these foreclosures are through the system we could see another decline in prices.” James Kowalski, executive director of Jacksonville Area Legal Aid, says he has clients who have tried for years to get their servicers to foreclose and take title to their homes. “There are literally thousands of borrowers who have been trying to hand the house back to the bank and they won’t take it back,” Kowalski says. “They can decide not to file, to rescind a notice of default, or to ask for continuances, and they’re doing it repeatedly in Florida. If you want any better proof that the banks are slowing down the process state-by-state, based on their own internal analysis, this is it. The banks control the pacing of the foreclosure process, not the homeowners, not the judges.”

Now given the quiet title issue, it will take some time for these properties to dribble onto the market. They’ll be in bad shape and go for rock bottom prices. But they would suit limited-debt-capacity gentrifiers. One can imagine that wrecks could be attractive to young people with student debt who can’t get a mortgage form a bank but might get a relative to provide a modest one. And said young person would need to be willing to put in a lot of sweat equity and have access to someone with construction skills.

New York had a successful homesteading program in Harlem in the bad days of the 1970s and 1980s for city-owned property that was very successful. Habitat for Humanity and similar organizations or small scale builders might also be interested in these properties as a play.

The biggest losers from this might well be private equity buyers. These rock bottom properties would compete with the plan that many of them have, to exit via sale. They would also compete with starter home products from homebuilders.

But there’s another big set of losers, namely, mortgage investors. Many mortgage backed securities from the bubble years have paid down substantially between foreclosures, refis, and normal sales. The mortgages associated with these zombie titles are still show in investor reports as having economic value (they are included in principal balances) when the servicers’ excuse for not foreclosing is that they have none (the cost of foreclosing exceeds what the bank could recoup by selling the property). These investors are going to have a rude awakening when they discover that the remaining value of the bonds is much lower than they think.

And this raises yet another troubling issue about bank conduct. When a borrower defaults, the servicer keeps advancing principal and interest to the investors as if the borrower is still paying. This process continues until the loan is non-recoverable. The concept was that the servicer would recoup the money it had advanced when the home was sold (the foreclosure costs, interest and principal advances and all fees are reimbursed before any money goes to the investor).But the pooling and servicing agreements never contemplated that many homes would wind up being worth less than the mortgage balance. That means when the servicer advances funds to the investors, he won’t be able to recover it all when the home is sold. That problem is particularly large with these zombie title homes.

So what are the servicers doing? Although we can’t prove it, is is almost certain that they are stealing cash from refinancings to reimburse themselves for these advances. This is not permitted under the pooling & servicing agreement, but since banks steal from homeowners and investors any way they can (the whistleblowers at Bank of America, PNC, and a new one at Wells Fargo all report endemic fee abuses, which ultimately come from investors), why should we expect anything different?

And that, dear reader, is why you should care about zombie title. You are paying for it. You are paying via your local government not getting property taxes it is due, and by state and local governments having pension shortfalls that lead to higher taxes and lower service levels (those pension funds were often large investors in MBS). So if measures are ever proposed to contend with some of these mortgage abuses, it’s in your interest to support them, whether or not you have a home with a mortgage on it or not. Put more simply, if you aren’t part of the bank looting operation, you can’t escape being a victim in more ways that you know.

Originally published by Naked Capitalism.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments