When news of David Miranda’s nine-hour detention at Heathrow broke on Aug. 19 and turned him into a household name overnight, cable news pundits and thousands of tweets percolated with speculation and far-flung theories about how willing a player Miranda was in the Glenn Greenwald–Edward Snowden surveillance scandal that had been making headlines for months.

One of those theories posited that the gaping social chasm between Miranda’s and Greenwald’s backgrounds suggested that the highly educated American lawyer turned whistle-blowing journalist with a background in the ruthless world of New York corporate law had cynically manipulated his younger, slum-raised, hunky, ostensibly ignorant boyfriend into being an unwitting human courier dispatched on a highly dangerous mission.

“I don’t mean to be unkind, but he was a mule,” Jeffrey Toobin, chief legal analyst for CNN, told Anderson Cooper in the days following Miranda’s detention. “He was given something — he didn’t know what it was — from one person to another at the other end of an airport.” Toobin said he believed the U.K. government was totally justified in detaining Miranda and that the Brazilian native “was lucky that they used the terrorism law” because he was ultimately not arrested.

After I spent several weeks with Miranda and Greenwald in and around their home in the upscale, artist-friendly Rio neighborhood of Gavea over the last month, one thing has become very clear: David Miranda knew exactly what he was doing. To believe he was played as some type of dupe or mule by Greenwald not only ignores the real nature of their relationship but also assumes that there’s some safer way to transport sensitive documents across the globe. Is there any device more fail-safe and secure than the person you love the most? Does Apple make that sort of product?

Miranda knew very well that he was traveling from Rio to Berlin to see Greenwald’s reporting partner, documentarian Laura Poitras, and that he would be returning through the U.K., all the time carrying a heavily encrypted flash drive directly related to the trove of documents that former and now notorious CIA employee Edward Snowden had vacuumed from the National Security Agency and had given to Greenwald earlier in the year.

As to the relative risk of this adventure, Greenwald and Miranda knew that others who made the same trek were, in the eyes of the authorities, much “hotter” and more conspicuous than Miranda. “Numerous Guardian employees who have worked heavily on this story flew in and out of Heathrow multiple times without incident,” Greenwald says, “including when they were carrying materials.” Three weeks before Miranda’s detention, Poitras herself — who met with Snowden in Hong Kong and wrote numerous articles about the documents — flew to London, entering the U.K., and had no problems. Why would they stop someone much more peripheral like Miranda? the couple reasoned.

“I have been involved in every aspect of Glenn’s life, why wouldn’t I be a part of this?” Miranda asserts over lunch at a fashion mall in Rio’s São Conrado neighborhood the next afternoon. “I think what Snowden did was heroic. Glenn and Laura’s reporting is so important. It caused a serious debate about privacy and internet freedom in my country and around the world. I’m so proud to be able to play any role at all in that. I’d go to jail for that.”

His already throaty voice is a little huskier from singing along to Justin Timberlake the night before. Miranda has the day off from a cramped school week that includes a major group project on branding and marketing for a local café. Miranda is in his final year at university, where he is majoring in communications. He would ideally like to become a marketing and communications specialist for a major media company, particularly one with a thriving video game department.

“Glenn and I have talked all the time about what doing these stories would do to our lives. Since we met, I’ve pushed him and supported him,” Miranda says. He starts counting on his fingers: “I’ve helped him negotiate contracts; I make sure he gets paid what he deserves — Glenn just wants to work and sometimes will do it for cheap.” Miranda’s list continues with ascending urgency. “When Glenn publishes NSA stories in foreign countries, I help reach out to press so the stories get the most exposure. For a while we considered starting our own website to publish the NSA documents; when Glenn thought The Guardian was taking too long to publish the first NSA story, I told him he had to make them know he would go somewhere else to publish if they delayed too much.”

“I was in Hong Kong,” Greenwald says, referring to his first meeting with Snowden in early June. “We were eager to have the world learn about this spying as soon as possible. And we didn’t want any fear-driven institutional constraints getting in the way.” Greenwald credits Miranda with pushing him to hold The Guardian’s feet to the fire and not delay on this bombshell publication.

“I had my chat box open on my laptop while talking to Guardian editors, and I had David on the phone in my ear, and he’s dictating what to write to them word by word. It was something like, ‘Please consider this my resignation if the article is not published by 5 p.m. today,’ and I was like, ‘Oh my god, David, I cannot say that!’” But Miranda kept pushing. Greenwald sent a more compromising, though still firm message. Before 5 p.m. that day, the first NSA story was published on The Guardian’s website.

“David is a grown, 28-year-old man,” Greenwald says, visibly bristling at the accusation that Miranda was an exploited errand boy. “He is the most insanely willful person I have ever met; it makes me crazy sometimes. He was an orphan and had to take care of himself very early on in a way few people do. So it’s absurd to think that I could manipulate him into anything he didn’t want to do. A lot of this is pure racism, classism, and ethnocentricity: Some white Americans see a nonwhite Brazilian who grew up poor and doesn’t speak perfect English, and so disgustingly assume that he’s dumb, naïve, and easily manipulated.”

Miranda’s life has been totally transformed and taken a radically different course since he laid his beach towel down next to Greenwald’s on a Rio de Janeiro beach eight years ago. “We knew we were fucking with power,” Miranda says.

But what has shocked both men is that somebody engaged in a journalistic endeavor like Miranda could be labeled a terrorist by the U.K. “I guess we should have known,” says Greenwald. “This is a country with a history of repressing press freedoms, that has no constitutional guarantee of a free press. I mean, they still have a queen. Is there anything more primitive and authoritarian than a fucking monarchy?”

Just how much bad blood simmers between these two men and the British government comes to the fore as Miranda recounts here, for the first time, the granular details of his Kafkaesque detention in Heathrow Airport. The news of this detention flashed globally on Aug. 19, but the chain of events that led to this incident began in an unkempt Hong Kong hotel room months earlier.

It was June when Snowden, Greenwald, and Poitras were working out of Snowden’s cramped, littered Hong Kong hotel room with Guardianreporter Ewan MacAskill, pushing out the most explosive stories about government overreach since the Pentagon Papers. Snowden offered Greenwald some advice before he headed back Brazil with a cache of NSA documents: Make a copy and give them to someone Greenwald trusts with his life. There needed to be contingencies, Snowden told Greenwald — a backup plan should Greenwald’s archive be damaged, confiscated, or if the exiled NSA contractor should ever be captured or disappeared.

“There’s only one person who fits that description, of course,” Greenwald says, reaching across the outdoor dinner table to Miranda. The floppy tropical fronds of the restaurant veranda hang motionless in the dank Brazilian dusk as Greenwald lightly brushes Miranda’s fingertips with his own. Miranda, sitting in front of a roiling fondue bowl, scrunches his lips sideways and nods with a cocksure smirk to Greenwald. “That’s right!” declares Miranda.

From Hong Kong, Greenwald told Miranda by Skype — they had not yet had reason to suspect their conversations would be monitored — he would be taking Snowden’s advice and in a few days would email Miranda a heavily encrypted copy of the NSA archive to be stored on a thumb drive or a cloud, in a place that nobody but Miranda would know. Miranda would not be able to access the documents — he would not have the encryption key — but there would always be an available copy should something happen to Greenwald’s.

“And that’s when it all started,” Miranda says in a once-upon-a-time tone.

It was with this Skype conversation, the couple believe, that Miranda became a target not only of government surveillance but intimidation to suppress Greenwald’s journalism. “The whole thing is disgusting,” Miranda snorts.

Miranda started making arrangements to fly to Berlin and stay with Poitras. The simplest reason, Miranda explains: “Laura doesn’t like to talk on the phone.” And there was plenty to talk about — primarily movie rights. Studios started courting Miranda, Greenwald, and Poitras for rights to their story since Poitras’ first images of an unshaven Snowden began to saturate the news cycle. (All signs point to a Sony-helmed production with Ed Norton perhaps playing Greenwald; Greenwald says he doesn’t care much which actor is chosen, but half-jokingly adds that only David Miranda could play David Miranda — “Who else could be so smoldering and broody?”) He planned to go Berlin to meet with Poitras and her editors to strategize on getting the best and “most serious” version of their story made into a movie, Miranda says.

“Plus,” Miranda adds playfully, “I needed a vacation!” Miranda originally planned to accompany Greenwald to Hong Kong in June but stayed in Rio to complete his finals. And there was some other business related to Greenwald and Poitras’ journalism that Miranda could help out with on this trip.

Originally, The Guardian was going to fly a staffer to Berlin in July to courier documents between Poitras and Greenwald for stories they were working on together. On the day scheduled for the staffer’s flight to Germany, he instead asked Poitras to just FedEx the documents to Greenwald. “The Guardian had just destroyed their hard drives under orders from the [Government Communication Headquarters], and the U.K. government was becoming increasingly threatening,” Greenwald says, a mild sympathy in his voice. “I think this employee’s supervisor was just totally freaked out.” The sympathy quickly gives way to a more incredulous agitation: “But FedEx-ing classified documents? That was obviously not something Laura or I were willing to do.” (When asked about this series of events, a spokesperson forThe Guardian said over email that the paper does not comment on its “process.”)

Poitras was also angered and disturbed by the suggestion. Guardian higher-ups eventually recanted and said they would be willing to have their employee fly to Berlin, but Poitras was unwilling to deal further with The Guardian over the issue. That left the question of how Greenwald would get the materials he needed. “David was going to Berlin to talk to Laura anyways,” Greenwald says, “and so he suggested that he just take the documents. Laura trusts David completely, so that became the new plan.”

Because Miranda was performing a service to support articles that were to be written for The Guardian, the newspaper paid for his trip and made his travel arrangements through London. Miranda flew to Berlin on Aug. 18 and did the typical club and upscale restaurant scene with Poitras and some of her friends in and around Alexanderplatz. Poitras and Miranda hashed out some details about movie rights — she was skeptical of signing anything that gives big studios access to her film archive or work.

Miranda decided toward the end of the trip to catch a later flight into London, where there was a short layover in Heathrow before continuing onto Rio. “I called the airline to change flights,” Miranda recalls, “and they wouldn’t let me. They didn’t give me any details, they just kept telling me they couldn’t do it. I knew the morning of my flight something bad was going to happen; I could feel it.”

Miranda and Greenwald now suspect the U.K. government was lying in wait to grab Miranda at Heathrow, knowing that he could be carrying documents or data from Poitras. Indeed, even the Obama White House was given an advance warning of Miranda’s detention but it isn’t clear with how much lead time. “There was a heads-up that was provided by the British government,” White House spokesman Josh Earnest said shortly after Miranda was grabbed.

“We didn’t tell anyone about my travel plans,” Miranda says. “Only me, Glenn, and Laura and a couple of people at The Guardian knew, so obviously the only way they could know what I was doing on this trip is if they were going through our emails and Skype logs.” Miranda’s suspicions that his detention was predetermined were confirmed last week at the initial hearing on his lawsuit against the British government. The government told the court it distributed a red-flag Port Circulation Sheet to its border agents in anticipation of Miranda’s arrival:

“Intelligence indicates that Miranda is likely to be involved in espionage activity which has the potential to act against the interests of U.K. national security … We assess that Miranda is knowingly carrying material the release of which would endanger people’s lives … Additionally the disclosure, or threat of disclosure, is designed to influence a government and is made for the purpose of promoting a political or ideological cause. This therefore falls within the definition of terrorism…”

When Miranda’s plane landed, he says, the flight staff announced that everyone would have to show their passports as they exited the plane and crossed onto the tarmac at Heathrow. Miranda queued up, showed his passport, and was immediately taken by two border agents to a sterile, white, windowless room several floors below the departure gates, isolated from the airport’s hustle and bustle.

“I thought I knew exactly what was happening,” Miranda says flatly. “I knew because Laura had talked about being detained before on other assignments and I just thought to myself, I will try to be as vague as possible.” Inside the neon-washed holding room furnished only with a table and four chairs, the agents confiscated Miranda’s bags, including a laptop, cell phone, and encrypted flash drive. Under Section 7 of the U.K.’s anti-terrorism law, officials have the right to examine property and search anything the detained person is carrying.

Once Miranda was seated across from the two agents, he told them he knew why they had detained him. “It’s because of the work my partner is doing,” Miranda recalls, voicing the same braggadocio and confidence he showed at the nightclub. “So what do you want from me?”

“What sort of work is your partner doing?” one agent, who identified himself as Two-Oh-Five-Oh-Six, inquired with a seemingly benign curiosity.

“Come on,” Miranda responded, agitated.

“We don’t know who your partner is,” the agent replied flatly.

Miranda asked if he could have a lawyer; the agents told him he could speak to a lawyer who would be limited to explaining the Terrorism Act to him. What was his lawyer’s name? They would ring him straight away.

“Glenn Greenwald,” Miranda snapped.

“Does he practice law in the U.K.?”

Miranda bluffed and said Greenwald did practice in the U.K., but after one of the agents consulted a registry over the phone they found that Greenwald was not, in fact, a solicitor in Her Majesty’s kingdom. The agents told Miranda he could have an attorney from their own approved list, but that they could only speak by phone and would not be present for the rest of the interrogation. Miranda refused: “I told them no, because I did not trust their chosen lawyers or their phones. I also thought when a lawyer Glenn hired or someone from The Guardian did finally come to meet me, the agents would tell me I already had a lawyer and not allow me to talk to anyone else.”

One of the agents asked Miranda for the passwords to his cell phone, laptop, and flash drive. When Miranda did not respond, agents grew sterner and told him again that under the Terrorism Act he could be sent to prison for not cooperating with their requests. Miranda relented.

“I became scared at that moment because I know that people get disappeared by the U.S. and U.K. governments if they claim you’re a terrorist,” he says. “I didn’t have the encryption keys to allow access to the documents, but I did tell them my passwords to my personal phone and laptop.”

Miranda’s laptop browser was open to his email. His cell phone contained everything one’s cell phone typically does: contacts, emails, texts, pictures — the type of pictures you take with your romantic partner. The agents also took from Miranda’s backpack a piece of paper that had one of the passwords for the outer shell of the flash drive, not to core data, say Miranda and Greenwald. That flash drive is the focus of Scotland Yard’s ongoing criminal investigation against Miranda, British officials say. In a statement given after Miranda’s release, Oliver Robbins, deputy national security adviser for the U.K.’s Cabinet Office, said the flash drive contained “approximately 58,000 highly classified U.K. intelligence documents” that were “entirely of misappropriated” materials. Robbins chastised Miranda for exercising “very poor judgment.”

Miranda and Greenwald both claim the U.K. government is lying about what that one seized password enables. “It is impossible that they could have access to the documents,” Greenwald insists. “David did have a piece of paper, and it did have a password on it, but it did not allow access to the actual documents because there were multiple encryption walls around it. All the password allows access to is a list of the documents and, in some cases, a summary of them. They are lying when they claim it allowed access to the documents themselves, trying, as usual, to scare their public into submitting to their assertions of radical authority.”

When the agents got the passwords from Miranda, all pretenses collapsed and the interrogation began in earnest. We can only rely on Miranda’s retelling of the subsequent hours spent in the Heathrow interrogation room, since U.K. officials have never released audio or visual from the detention. Indeed, Miranda says when he asked if agents were recording, they said there was no recording allowed during the initial interrogation under the Terrorism Act — though the words “terrorism,” “bomb,” “weapon,” “murder,” and “destruction” were not mentioned by the agents, nor were any of the typical nouns often associated with endangering the lives of others. “They never once asked me a single question about terrorism,” Miranda says.

A rotating tag team of seven agents asked Miranda questions ranging from his personal life with Greenwald to his family background to his own politics. Miranda’s request for a translator was brushed aside, and all nine hours were spent being interrogated in English.

“First they tried to pit me against Glenn,” Miranda recalls. The agents asked Miranda whom he went to the nightclubs with in Berlin. “Boyfriends,” Miranda replied, meaning male friends. Did Glenn know about these boyfriends? “No.” How would Glenn feel if he knew Miranda was out with the other men? “Fine.” They asked if Miranda had been in contact with Edward Snowden. “No.” Were his family members political? “No.” They asked about Miranda’s political views. Did he support the street protests in Brazil? “Yes.” Did he participate in the protests? “No.”

“They offered me water, but they didn’t pour it front of me,” Miranda says with a note of pride. “So I said no. I didn’t trust them for a second, I never had a drink of water while I was there, and I never got up to go the bathroom.”

Back in Brazil, Greenwald was asleep at home. “I get a phone call at 6:30 in the morning, which you know is bad news,” Greenwald says. A man who gave no name identified himself as a “security official at Heathrow Airport” and said Miranda was in detention under the Terrorism Act. He told Greenwald that Miranda had been held at that point for three hours and that they could hold him up to nine hours, at which point they could arrest him, release him, or ask a judge for additional time to interrogate.

“I look it up, and it’s, like, less than 3% of people are held for more than an hour under that law, and less than .3% are held for more than three hours, and if you are held for more than an hour you often end up arrested,” Greenwald adds. “I definitely thought they were going to arrest him or haul him before a judge to seek more detention time, which would not go in our favor.” The interrogation reached its fifth hour when an agent came to tell Miranda that they had contacted Greenwald.

Greenwald spent the next several hours maniacally stress-eating Doritos, emailing everyone he knew at The Guardian, and chatting with Edward Snowden and Laura Poitras online. Between 2006 and 2010, Poitras herself was detained and interrogated more than 40 times after producing an Oscar-nominated documentary called The Oath about the U.S. occupation of Iraq and while working on a film about extremists in Yemen called My Country, My Country. “Ironically,” Poitras tells me via email, “the detentions stopped following an article Glenn wrote about an incident at Newark airport where agents threatened to handcuff me for taking notes because they said my ‘pen was a weapon.’”

Poitras says that the most invasive border crossing she experienced occurred in 2010 at John F. Kennedy Airport: “They seized my laptop, phone, and camera and held them for 41 days,” Poitras recalls. “When I got my equipment back, the photos on one device had been viewed and a slide show had been created.”

After eight hours and 20 minutes, Miranda recalls, he was allowed to meet lawyers from The Guardian. After exactly nine hours, Miranda was released and told he would not be immediately charged. Miranda was told to wait in the customs inspection lounge while the agents tried to find a direct flight back for him to Rio. Miranda asked that his personal electronic devices be returned but was told they were now evidence in a pending criminal investigation and he could not have them back until the investigation was closed.

Another two hours passed with the British agents still holding his passport. The agent arranging Miranda’s travel then told him there were no more flights back to Rio that evening and that he would have to go through customs, stay the night in London, make his own arrangements with his own funds, and return to the airport to fly out the next day.

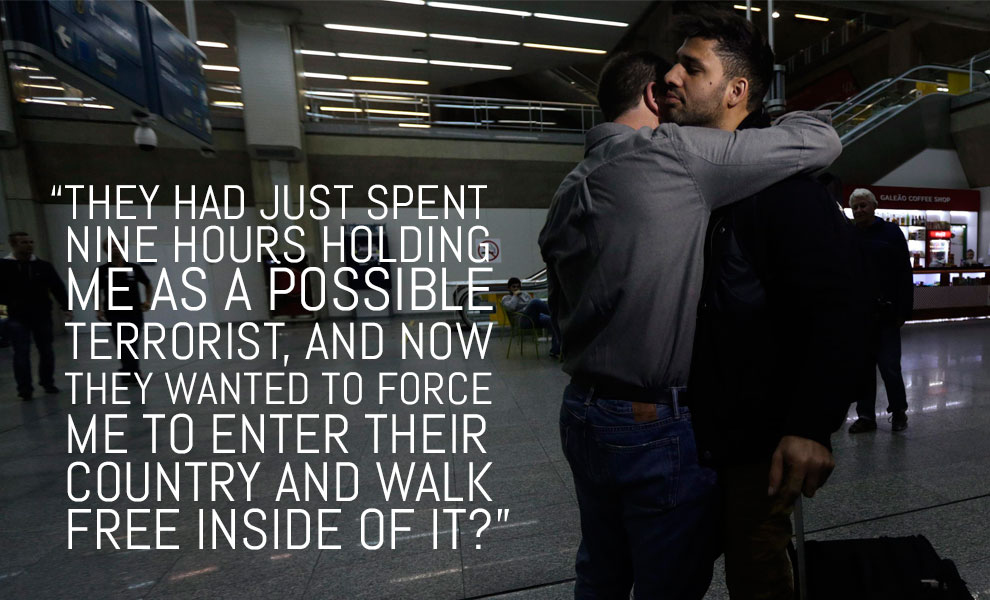

“That’s when I went crazy, because I was sure that if I walked out of the airport, they would find some reason to arrest me and disappear me in some prison,” Miranda says. “Also, they had just spent nine hours holding me as a possible terrorist, and now they wanted to force me to enter their country and walk free inside of it?”

He then did what H.L. Mencken once referred to as “hoist[ing] the black flag.” Miranda began to scream: “I am a Brazilian citizen!” The few dazed travelers coming in from their evening flights, waiting to have their passports stamped began to turn their heads. “I’m being held here against my will!” The customs agents froze. “I want to go home! They will not let me go home! They took my passport!” Within 20 minutes of Miranda’s screaming episode, the agents miraculously booked a direct flight back to Rio that night and returned his passport at the last moment as he entered the business class cabin.

“The day after I got home, Glenn yelled for me to come into the living room,” Miranda recalls. Greenwald had logged into his own Skype account. “Look,” Greenwald said, pointing to his contact list. A little green dot appeared and announced “David Miranda is online” but David Miranda was not online — he was standing next to Greenwald as he got dressed, getting ready to go to school. Miranda had not signed into his Skype account since his laptop was confiscated at Heathrow. “Those assholes in London were going through my Skype account,” Miranda says.

Now Miranda and Greenwald are fighting back, challenging the legality of Miranda’s detention, and they had their first hearing in front of a three-panel judge in London on Nov. 6. Miranda’s lawyer, Matthew Ryder, argued that he was carrying source materials for journalism, which was in the “global public interest.” For the U.K. government to invoke the Terrorism Act in order to search and seize his materials was using the law for an “improper purpose” and created a “disproportionate interference with Miranda’s right to freedom of expression.”

Ryder argued if the U.K. wanted to stop Miranda at Heathrow, they could have done so under normal law, which would have given him some protections as a journalist. The legal proceedings could drag on for months, especially as Greenwald’s latest revelations involve the British government. Greenwald’s recent departure from The Guardian has freed him from the draconian British press laws that could have hampered the U.K.-based daily from breaking this new round of stories.

“There’s a good chance that, at the lowest level, David won’t win his court case in the U.K.,” Greenwald says, plunking a skewer of raw shrimp into his fondue bowl.

“Don’t say that,” Miranda says, clicking his cheek in disapproval. “I hate it when you talk like that. It’s so negative.”

“It’s just that it’s a post-9/11 era,” Greenwald says gently. “I’ve just seen all these judges who are so subservient, who will get down on their knees in deference every time the state utters the words ‘terrorism’ or ‘national security.’” He adds, to get back in Miranda’s good favor, “They’re trying to make an act of journalism into terrorism.”

If you ask Miranda about the dynamics between him and Greenwald (and the 10 stray dogs the couple have adopted), Miranda describes himself as the alpha. “I’m the pack leader,” Miranda tells me, grinning. “A son of Apollo.” Miranda tends to dominate through his moods; he’s quick to show his disdain, annoyance, or disappointment. “I’m a very emotional person,” Miranda says, putting both tan hands to his Armani-clad chest. “Like, you will always know how I’m feeling and when I’m feeling it.” Greenwald, a former champion high school debater, city council candidate, and courtroom litigator, tries to counter Miranda’s occasional brooding or temper with point-by-point arguments to the contrary.

“We yell when we fight,” Miranda admits, “but we never break up. There’s something in the universe that says we have to be together. I never met anyone like Glenn — he’s my husband and I don’t know where either of us would be without each other.” Miranda says early on in their relationship, when he was “young and more bull-headed,” he would devolve into fits of jealousy and despair when Greenwald would have to travel to New York to wrap up his law practice.

“I have attachment and abandonment issues because of how I grew up,” Miranda says with the self-awareness and diagnostic certainty that comes with long hours in a shrink’s office.

Miranda grew up in Jacarezinho, a favela town of 60,000 inhabitants, built along the railroad tracks of northern Rio. Miranda’s mother worked in Jacarezinho as a prostitute. He has four other brothers from unknown fathers whose whereabouts he’s unfamiliar with. When he was 5 years old, his mother died of ovarian cancer derived from a sexually contracted disease, and he was sent to live with one of his mother’s friends, who also worked as a prostitute.

“She slapped me the day of my mother’s funeral because I wasn’t crying,” Miranda recalls. “I didn’t really know my mom, so I didn’t know what I was losing.” Miranda doesn’t have many memories of his mother — the few he does are of passing kindness: extra treats when she would come home in the mornings, singing songs, letting him play with a bunny rabbit while she attended to men. The woman Miranda lived with had several sons and daughters who became Miranda’s surrogate siblings.

Miranda formed the closest bond to one of his adopted teenager sisters, a moody, defiant young girl who used to bring home books about witchcraft and love spells. The two would pore over the occult, Greek myths, and listen to early ’90s rock together. When she began to pull away from the family, Miranda, at age 13, dropped out of school, and moved into a run-down apartment with some of his older cousins to claim his own independence. “I kept reading books and magazines on the bus when I’d go to work.” Miranda worked through his teenage years at a car wash, handing out sidewalk flyers for a local dentist, then working for the dentist directly. Eventually he moved into a sales position for the Brazilian lottery. “I was actually very happy at that time because I was free and totally in charge of my life.” But to this day Miranda refuses to set foot on a Rio bus, thanks to too many days spent riding in cramped buses with too little money.

The winter Miranda would turn 20, he met a Jewish-American lawyer on an Ipanema beach. Their courtship was intense and speedy, with the couple moving in together by week’s end. After two years of living together, they became common-law husbands.

Eventually Greenwald insisted that Miranda go back to school. “I just thought it was a tragic waste of intelligence for David not to continue his education,” Greenwald says. “He didn’t want to be reliant on me, and I didn’t want that either.” It took several years, but Miranda completed high school and is now in his final year of university.

At dinner, Greenwald and Miranda talk more about Heathrow and the detention; they rehash a few of Miranda’s zingers on a recent interview with Anderson Cooper. Whatever squabbles the couple has had in their eight years together — there have been some — they are still as bonded and protective over each other as ever.

“Heathrow was no big deal compared to the 12 hours I thought I was going to be murdered in my house when Glenn disappeared,” Miranda says with a flustered laugh. Greenwald begins to blush a bit.

Miranda spent a Sunday evening in early June partying until daylight: partly to celebrate Greenwald’s triumph for publishing the first NSA story, partly to avoid being alone in the house while Greenwald was in Hong Kong. This is the same weekend Greenwald told Miranda over Skype he was giving him his own copy of the NSA archives for safekeeping. Miranda went out for the evening and returned home at 6 a.m. He fed the 10 dogs, which bark, growl, and snarl at the slightest noise emitting from inside or around the couple’s large two-story house. Miranda plopped down at the kitchen table, checked his email on his laptop, and then dragged himself upstairs for a power nap. Four hours later, Miranda groggily walked downstairs and his laptop was gone.

“I looked everywhere, for over an hour, and I couldn’t find it,” Miranda says. “Then I thought, O.K., someone broke in while I was asleep.” Miranda assumed that perhaps it was someone he was friendly with. “Maybe it was someone who knew I was married to Glenn and wanted to make money by breaking into our house and getting one of our laptops.” But how did they get past his dogs? That’s when Miranda started to get scared, but he didn’t want to throw Greenwald’s focus with talk of black-op home invasions.

Miranda went to bed early that evening and awoke the next morning to banging on his front door. Two men who said they were from the electric company came to shut the power off. “They said we were late on our bill, which is impossible because we’re never late.” He showed the men bills to no avail. The power went off. When Miranda called the electric company from his cell phone, the representative said their account was up to date but had some hold on it she could not undo. Greenwald was still in the air, unreachable on his flight between Dubai and Rio. Adding to Miranda’s anxiety was Snowden’s unknown whereabouts at the time — he had gone into hiding 48 hours prior.

“I spent the next 10 hours at home, with my dogs, with no electricity, waiting for Glenn to come home,” Miranda says. “But maybe he wasn’t going to come home! I started going crazy. I thought anything could happen to me, like bad things, and it could look like an accident or whatever. I stayed up all night in the dark.”

Greenwald arrived the following morning to a frantic Miranda. “I thought they got Snowden,” Miranda said, near tears. “I thought they got you.”

Greenwald thought it was a strange series of events but nothing like the sort of paranoid nightmare Miranda imagined. He dismissed Miranda’s consternation with a hug and some soothing words.

“Looking back,” Greenwald says, tilting his wine, a bit repentant and conciliatory, “I realize that David’s assumptions were more rational than mine. I didn’t want us to become those paranoid, creepy people who attribute every inexplicable event in their lives to the CIA.” This change of perspective came after he mentioned the events to one of The Guardian’s lawyers, who told him that “he had talked to all these people in the intelligence community and he had heard that the CIA has one of the most robust presences in Rio and that the CIA station chief in Rio is ‘notoriously aggressive.’”

With Greenwald’s admission, Miranda looks pleased and vindicated and orders the check. “Ultimately, as harrowing and unjust as it was, the U.K. actually did us a favor,” Greenwald says as we head toward the car. “They revealed how abusive the U.S. and U.K. can be with power, which is a major point of the reporting I’m doing; they humanized the story, and they gave a platform for my charming and admirable husband to speak out.”

While Scotland Yard has been threatening a criminal charge to be brought against Miranda for months now, it’s unlikely any formal charges will be made, stemming in part from the fact that the British government has not been able to hack inside the encrypted flash drive. If the U.K. government was able to break into the flash drive and attempted to charge Miranda with espionage, it’s highly unlikely the Brazilian government would extradite him.

In the meantime, Miranda is not changing his plans. “I’m going to finish university next year and then I might take some post-graduate classes in journalism,” Miranda says. Then he plans to enter to enter the job market as a branding and communications specialist.

“We know we are probably under constant surveillance,” Miranda says, as we pile into the couple’s cherry red Jeep, “but we don’t give a fuck. We’re not going to be stupid.”

“But we’re not going to live our lives in fear,” he adds as the car pulls away. “Now everyone in the world is watching, bitches!”

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments