A startup founded by a young and outspoken supporter of President Donald Trump is among the latest tech companies to quietly win a contract with the Pentagon as part of Project Maven, the secretive initiative to rapidly leverage artificial intelligence technology from the private sector for military purposes.

Anduril Industries is the latest venture of Palmer Luckey, the 26-year-old entrepreneur best known for having founded the virtual reality firm Oculus Rift. Luckey began work on Project Maven last year, along with efforts to support the Defense Department’s newly formed Joint Artificial Intelligence Center, according to documents viewed by The Intercept.

The previously unreported Project Maven contract could be a boon for Anduril’s bottom line. Founded in 2017, the company has said it seeks to remake the defense contracting industry by incorporating the latest innovations of Silicon Valley into warfighting technology.

Last year, Google’s involvement with Project Maven stirred a controversy inside the tech giant. The company had signed a contract with the Defense Department to develop artificial intelligence that could interpret video images in order to improve drone targeting. But after the contract’s disclosure sparked an internal rebellion among employees, Google allowed its contract to expire. The Google flap and the wider military drive to adopt commercial artificial intelligence technology unleashed a fierce debate among tech companies about their role in society and ethics around advanced computing.

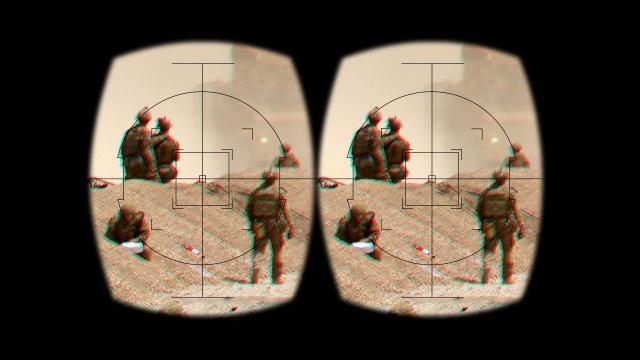

Anduril Industries is developing virtual reality technology using Lattice, a product the firm offers that uses ground- and autonomous helicopter drone-based sensors to provide a three-dimensional view of terrain. The technology is designed to provide a virtual view of the front lines to soldiers, including the ability to identify potential targets and direct unmanned military vehicles into combat. The first phase of the research has been completed, according to the documents reviewed by The Intercept, with initial plans to deploy virtual reality battlefield-management systems for the war in Afghanistan. (Anduril and the Pentagon did not respond to requests for comment.)

Luckey dropped hints about Anduril’s involvement in the project last November in Lisbon, Portugal, at the Web Summit, a technology conference. “We’re deployed at several military bases. We’re deployed in multiple spots along the U.S. border,” Luckey said, cryptically adding: “We’re deployed around some other infrastructure I can’t talk about.” He also discussed how he hoped the military would apply Anduril’s technology.

“What we’re working on is taking data from lots of different sensors, putting it into an AI-powered sensor fusion platform so that you can build a perfect 3D model of everything that’s going on in a large area,” Luckey said. “Then we take that data and run predictive analytics on it, and tag everything with metadata, find what’s relevant, then push it to people who are out in the field.”

“Practically speaking, in the future, I think soldiers are going to be superheroes who have the power of perfect omniscience over their area of operations, where they know where every enemy is, every friend is, every asset is,” he said. Luckey said he thinks it is “unlikely” that soldiers of the future will directly carry weapons in the field; instead, they would remotely operate machines and weapons from far away.

Anduril previously garnered attention for its efforts to help U.S. Customs and Border Protection create a “virtual wall” at the U.S.-Mexico border. The initial 10-week demonstration used Anduril’s Lattice technology to monitor a stretch of land along the Rio Grande Valley. The system reportedly helped the government identify and apprehend 55 unauthorized individuals crossing the border.

The company has also publicly acknowledged work to develop perimeter defense monitoring around two U.S. Marine bases.

Anduril’s pitch deck, the presentation it provided to solicit investors, imagines a future of warfighting by means that might look like science fiction to the average observer. The company is pushing battlefield management technology capable of utilizing long-range bombers and swarms of military attack drones. The firm has reportedly rented a warehouse in Oakland, California, to develop at least one remote-control tank, designed for fighting California wildfires.

A defense contractor in flip flops

Palmer Luckey stands out among other defense industry executives. In contrast to the buttoned-down image of executives at Lockheed Martin or Northrop Grumman, he typically appears in public wearing flip-flops and a partially unbuttoned Hawaiian shirt. And he stands out in other ways: Unlike other tech industry leaders, Luckey is unabashedly partisan. Being an avowed supporter of the Republican Party has made him a lightning rod in Silicon Valley.

The son of car salesman, Luckey was homeschooled by his mother in Long Beach, California. He got his start by parlaying his passion for tinkering with video game-optimized home computers into a virtual reality business. Using funds raised on Kickstarter, Luckey developed a new model for virtual reality headsets at age 17. Four years later, he sold Oculus Rift to Facebook for over $2 billion, earning him an estimated fortune of around $700 million.

During the 2016 election, Luckey posted on pro-Trump forums on Reddit, encouraging community members to develop memes critical of Hillary Clinton. He donated $10,000 to a group called Nimble America, which paid for a billboard stating that Clinton was “Too Big to Jail.”

Amid the ensuing controversy, Palmer lost his job at Facebook, which has adamantly denied that he was let go over his political views. According to the Wall Street Journal, however, Palmer retained an employment lawyer and negotiated a $100 million payout corresponding to bonuses and stock options that he would have had if he had stayed on at Facebook.

In a detailed profile of Anduril, Wired magazine reported that Luckey was first inspired to develop a military technology company through an event hosted by billionaire investor Peter Thiel, another Silicon Valley conservative. At a 2016 retreat in Canada, Luckey met Trae Stephens, a former intelligence official who works at Thiel’s venture capital firm, Founders Fund.

The pair bonded over an interest in reshaping defense contracting using the incentives and structures of the tech startup scene. Stephens had previously worked at Palantir, the secretive data-crunching company backed by Thiel, which is known for its work on behalf of spy agencies and the military. (Both Palantir and Anduril are references to the classic fantasy trilogy “Lord of the Rings”; Anduril is the unbreakable sword used by one of the series’s protagonists.)

Thiel’s high-profile support for Trump during the 2016 election gave him influence with the new administration. Stephens, the Thiel deputy, was appointed to the group on Trump’s transition team that dealt with the new administration’s move into the Defense Department. By March 2017, Luckey had left Facebook and was ready to work with Stephens on launching a new company focused on weapons systems.

The military-tech complex

Anduril needed talent, political connections, and an injection of capital. Enter the Founders Fund, Thiel’s venture capital firm. Several Palantir alumni quickly joined up. Stephens came on as Anduril’s chair and another Founders Fund partner provided seed funding. Other executives followed suit, including Brian Schimpf, the former director of engineering at Palantir, who now serves as chief executive at Anduril.

The timing of Anduril’s founding was fortuitous in many ways. Under the Obama administration, the government had begun massive efforts to swiftly incorporate commercial technology into its security efforts. In 2015, both the Department of Homeland Security and the Defense Department opened satellite offices in Silicon Valley as beachheads to coordinate partnerships with the private sector. The Defense Department opened a Defense Innovation Unit office in Mountain View, California, where Google is based. And the Homeland Security opened its Silicon Valley Innovation Program in Menlo Park, California.

In 2017, as part of an initiative that had begun the previous year, the Defense Department also unveiled the Algorithmic Warfare Cross-Functional Team, known as Project Maven, to harness the latest artificial intelligence research into battlefield technology, starting with a project to improve image recognition for drones operating in the Middle East.

This wave of outreach from the government provided a unique entry point for Anduril, which partnered with the Department of Homeland Security’s satellite office to successfully pitch its test project for the virtual wall. As Luckey recently explained to Defense and Aerospace Report, a trade publication, he also worked closely with the Pentagon’s Defense Innovation Unit, crediting its former director, Raj Shah, with making his company possible.

The Defense Innovation Unit, said Luckey, proved “that people in Silicon Valley could actually get stuff into production, actually do work with the government.” He added, “I don’t think that I would have started this company if it wasn’t for the work of people like Raj Shah doing great work and proving that you actually could get into it.”

Lobbying and political donations

Building out major government contracts is an inherently political endeavor — something that appears not to be lost on Luckey. Publicly filed lobbying disclosures show that Anduril paid $290,000 last year to Invariant, a lobbying firm founded by Heather Podesta, a Democratic fundraiser known for her extensive relationships in Washington, D.C., including with Hillary Clinton. The lobbying effort focused on shaping the border security appropriations issued by Congress, as well as on educating lawmakers on “artificial intelligence and autonomous systems and their application to military force protection,” according to the filings.

Luckey also opened his wallet to the powers that be in Congress and the White House. He donated $100,000 to Trump’s inauguration through a company he founded and gave over $670,000 to congressional Republican campaign funds over the last two years.

Rep. Will Hurd, R-Texas, a former CIA agent turned moderate border-district lawmaker, received a $2,700 donation. Hurd worked to help Anduril find a volunteer land owner to test its sensor technology along the border, according to Wired. Hurd later sponsored legislation to finance a virtual border wall likely using Anduril’s technology.

Among his political largesse, Luckey donated to political action committees supporting Trump, the senior lawmakers on the defense and appropriations committees, and a number of controversial conservative lawmakers, including Rep. Steve King, R-Iowa, who has defended white supremacy and questioned the contributions of nonwhite people to society.

In previous interviews, Luckey has sharply criticized traditional defense contracting, noting that the iPhone and other commercial technology innovations were developed with massive incentives, rather than the “cost-plus” model preferred by the Pentagon. That approach has seen the Defense Department negotiate with contractors to provide a fixed price for expenses and profits, one that, in Luckey’s telling, has limited the military’s ability to encourage the kind of breakthrough technologies needed for the future of war.

In a white paper filed with the Defense Department’s National AI Strategic Plan last year, Anduril urged officials to consider the ambitious approach by the government in China with regard to AI technology. China, an Anduril employee wrote in the paper, has provided a “multibillion-dollar national investment initiative to support ‘moonshot’ projects, start-ups and academic research in A.I.”

Even as it seeks to shake up the model for contracts, though, Anduril is also embracing the traditional approach.

In November, the company announced its first major revolving-door hire. Anduril brought on Christian Brose, a former top staffer with the Senate Armed Services Committee, which oversees defense spending, as its head of strategy. Brose formerly worked under the late Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., and served as a speechwriter to then-Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. Two months later, Anduril formally joined the National Armaments Consortium, a nonprofit that facilitates bids by traditional defense contracting firms for business with the military.

No “Digital Geneva Convention”

As the military worked to bring in leading Silicon Valley firms as contractors, the resulting relationships have sparked massive resistance from workers, many of whom have argued that they became engineers to make the world a better place, not a more violent one.

After the The Intercept and other media outlets revealed that Google had been quietly tapped to work on Project Maven, applying its AI technology to help analysts identify drone targets on the battlefield, thousands of workers protested the contract.

The uprising led Google to announce that it would not renew its contract with the military on the initiative. Microsoft, too, faced internal opposition as the company prepared work on a $480 million contract with the Army to develop augmented reality headsets for soldiers.

The ethical debates that have rocked large technology companies — Amazon, Salesforce, and others have similarly faced worker protests over contracts on immigration enforcement — have presented Anduril with an opportunity.

Despite the various protests around Silicon Valley, Anduril’s brash attitude has not prevented it from recruiting top engineering talent. In its white paper filed with the Defense Department’s National AI Strategic Plan last year, Anduril boasted that it has recruited engineers from top tech firms like General Atomics, SpaceX, Tesla, and Google.

In an opinion column for the Washington Post, Luckey and Stephens sharply criticized Google for abandoning the U.S. government by rejecting Project Maven. “We understand that tech workers want to build things used to help, not harm,” the pair wrote. “We feel the same way. But ostracizing the U.S. military could have the opposite effect of what these protesters intend: If tech companies want to promote peace, they should stand with, not against, the United States’ defense community.”

What was left out of the column, however, was that, as the piece went to print, Anduril was beginning its own work on Project Maven.

In interviews and public appearances, Luckey slammed engineers for protesting government work, arguing that those claiming conscious opposition to military work are among a “vocal minority” that empowers American adversaries abroad. Moreover, he said that the Defense Department has failed to connect with top tech talent because many engineers are “stuck in Silicon Valley at companies that don’t want to work on national security.”

In Anduril, Luckey is presenting a company that is unapologetic about its work capturing immigrants or killing people on the battlefield. The U.S., Luckey argued in a previous interviews, “has a really strong record of protecting human rights” and should be trusted to use AI without any ethical constraints.

“The biggest threats are not going to be Western democracies abusing these technologies,” he told the audience at the Web Summit in Lisbon. The real enemies are China and Russia, both of which have invested in AI military technology.

China is not only investing in AI, but has unfair advantages to develop the technology using its entire population as a data training set through use of mass surveillance to run experiments. In contrast, Luckey told Defense and Aerospace Report, the U.S. can train its AI software “in industry, in enterprise, in national security.” The U.S., Luckey went on, could test AI “using our current military advantage to train future AI developments and we need to start using our current military advantage.” He called for employing these technologies in ongoing “large-scale conflicts” around the world.

Asked in Lisbon about a digital Geneva Convention or another ethical rulebook to govern the use of AI weaponry, Luckey was forthright in his rejection of the idea.

“That’s not really going to solve the problem,” he said. “I have no hopes that a digital Geneva Convention, whatever it will be, will prevent China from using surveillance tools to watch every citizen in their country. I have very little confidence that it will prevent Russia from building autonomous systems that can acquire and fire on targets without any kind of human intervention whatsoever.”

Ethics experts have criticized the development of AI-based weapons, noting that the lethal autonomous weapons could be hijacked by hackers, kill without clear explanation, or lead to catastrophic accidental conflict if weapons are used as escalation in response to an incident that appears to be an act of war. Moreover, as humans are removed from face-to-face combat, the dehumanization of lethal decisions could lead to more killing.

Luckey hasn’t proffered any direct answers to the questions being raised over the use of artificial intelligence in warfighting. Anduril, however, has stated that it will not sell to Russia or China, but would be willing to sell its products to U.S. allies. A request for comment about whether the company would sell to Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, or other undemocratic U.S. allies was not returned.

Among the many Palantir alumni who joined Anduril, one name sticks out to those concerned with abuse of civil liberties and human rights. In May of last year, the firm hired former Palantir executive Matthew Steckman.

Steckman took a lead role in the HBGary Federal scandal in 2011. In the scandal, a cache of hacked emails showed that Palantir and two other defense contractors had cooked up a plot to spy on journalists, trade unions, and activists on behalf of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the largest pro-business lobby in America. The plot included hacking target computers and using social media analysis to monitor the behaviors of a large set of left-leaning figures and journalists viewed as sympathetic to Wikileaks, including The Intercept’s Glenn Greenwald. In negotiations with the Chamber’s law firm, Steckman wrote at the time that he and another Palantir executive were “spearheading this from the Palantir side.”

After the plan was revealed, Palantir briefly placed Steckman on leave. He is now at work as head of corporate and government affairs at Anduril.

One thing is clear: Luckey wants to win — in every way imaginable. The U.S.’s goal, Luckey said at the Web Summit, should be dominance and beating other foreign adversaries to control the best artificial intelligence technology. “You have to be the leader,” he said. “Technological superiority is a prerequisite for ethical superiority.”

Originally published by The Intercept