Eradicating blank spaces on maps of the “dark continent” was an obsession of Western powers during the 19th-century scramble for Africa. Today, a new scramble is underway to eradicate a different set of blank spots. The U.S. military has, since 9/11, engaged in a largely covert effort to extend its footprint across the continent with a network of mostly small and mostly low-profile camps. Some serve as staging areas for quick-reaction forces or bare-boned outposts where special ops teams can advise local proxies; some can accommodate large cargo planes, others only small surveillance aircraft. All have one mission in common: to eradicate what the military calls the “tyranny of distance.” These facilities allow U.S. forces to surveil and operate on larger and larger swaths of the continent — and, increasingly, to strike targets with drones and manned aircraft.

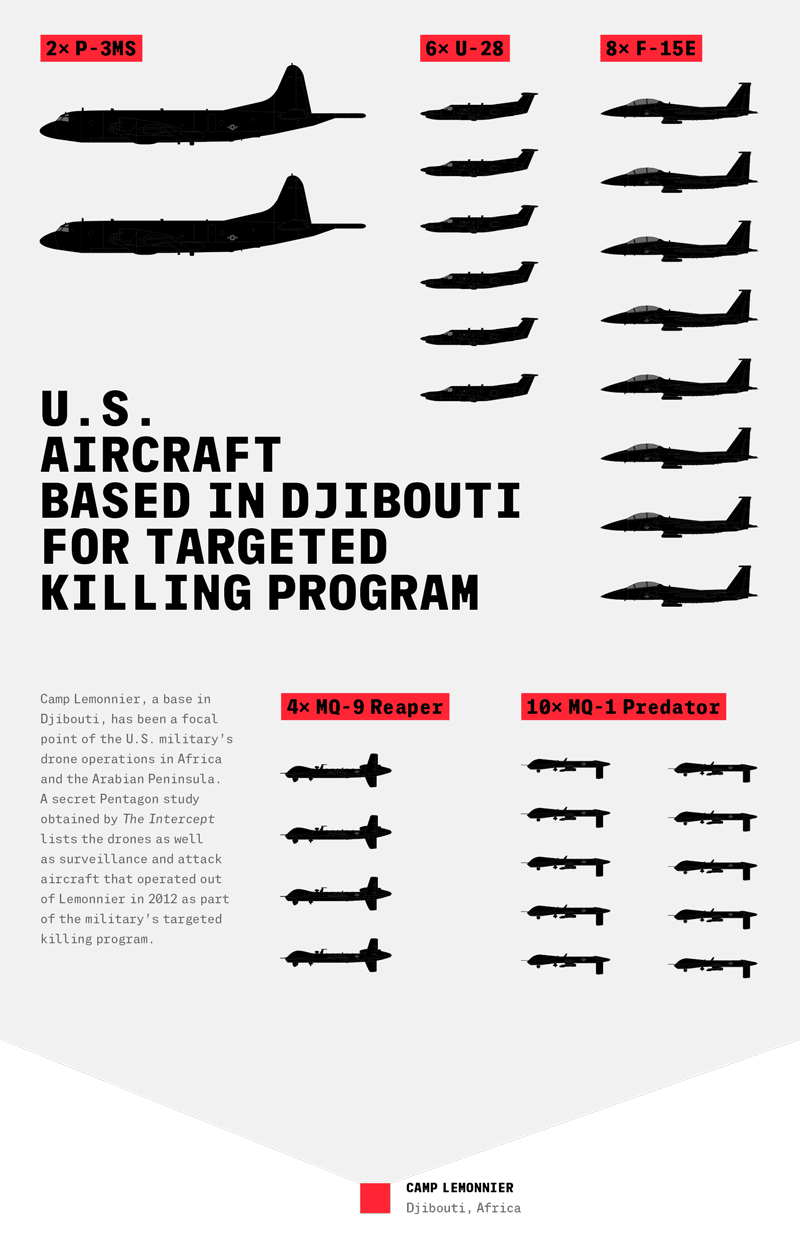

According to an internal 2013 Pentagon study obtained by The Intercept on secret drone operations in Somalia and Yemen between January 2011 and summer 2012, a secretive unit known as Task Force 48-4 carried out a shadow war in the region. The task force, with its headquarters at Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti, operated from outposts in Nairobi, Kenya, and Sanaa, Yemen. The aircraft it used — manned and remotely piloted — were based out of airfields in Djibouti, Ethiopia, and Kenya, as well as ships off the coast of East Africa.

U.S. Africa Command — the umbrella organization for U.S. military activities on the continent, known as Africom — insists that it maintains only a “small footprint” in Africa and claims that Camp Lemonnier, a former French Foreign Legion outpost, is its only full-fledged base. However, a number of new facilities have been opened in recent years, and even Defense Secretary Ashton Carter has acknowledged that Lemonnier serves as “a hub with lots of spokes out there on the continent and in the region.”

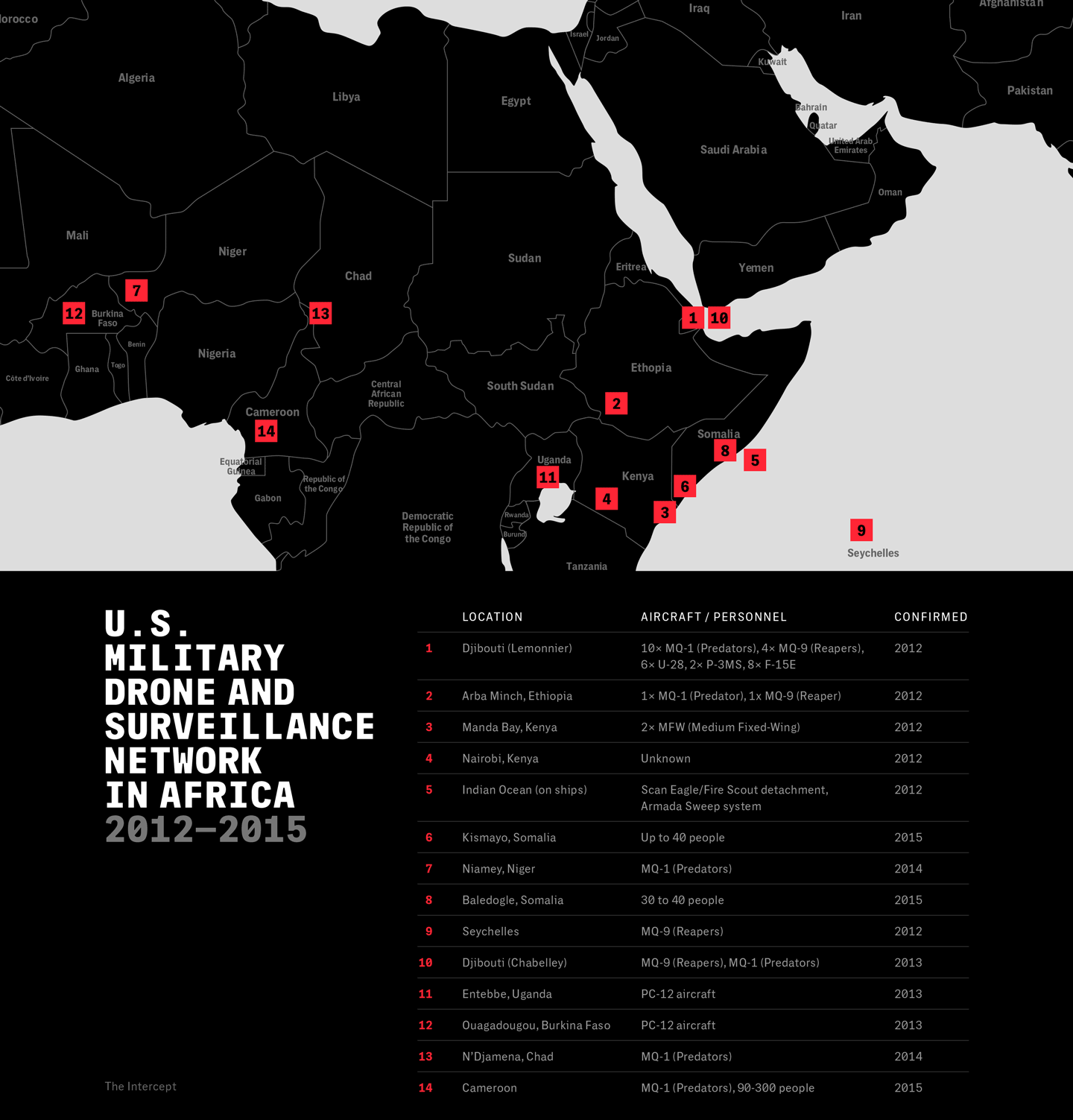

One of those spokes can be found just 10 kilometers southwest of Camp Lemonnier. After numerous mishaps and crashes, drone operations were moved from the camp to the more remote Chabelley Airfield in September 2013. Predator drones have also been based in the cities of Niamey in Niger and N’Djamena in Chad, while Reaper drones have been flown out of Seychelles International Airport. The Pentagon study, conducted by the Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance Task Force, also notes that, as of June 2012, there were two contractor-operated drones, one Predator and one Reaper, flying out of Arba Minch, Ethiopia.

Off the coast of East Africa, a detachment equipped to dispatch a Scan Eagle, a low-cost, low-tech drone used by the Navy, or an MQ-8 Fire Scout, a remotely piloted helicopter, added to the regional array of surveillance assets, as did those associated with “Armada Sweep,” a ship-based system for collecting electronic communications. Additionally, two manned fixed-wing aircraft were based in Manda Bay, Kenya. Recent reports also indicate that the military’s Joint Special Operations Command, or JSOC, is now working out of two bases in Somalia — one in Kismayo, the other in Baledogle.

While generally austere, many of these bases — including the airfields in Chabelley and Manda Bay — have expanded in recent years, with more on the way. Last year, for example, Capt. Rick Cook, who at the time was chief of Africom’s engineer division, mentioned the potential for a “base-like facility” that would be “semi-permanent” and “capable of air operations” in Niger. The National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal year 2016, introduced in April, requests $50 million for construction of an “Airfield and Base Camp at Agadez, Niger … to support operations in western Africa.”

Since 9/11, a multitude of other facilities — including staging areas, cooperative security locations and forward operating locations — have also popped up (or been beefed up) in Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Gabon, Ghana, Kenya, Mali, Senegal, South Sudan, and Uganda. A 2011 report by Lauren Ploch, an analyst in African affairs with the Congressional Research Service, also mentioned U.S. military access to locations in Botswana, Namibia, Sao Tome and Principe, Sierra Leone, Tunisia, and Zambia. According to Sam Cooks, a liaison officer with the Defense Logistics Agency, the U.S. military has struck 29 agreements to use international airports in Africa as refueling centers. These locations are only some of the nodes in a growing network of outposts facilitating an increasing number of missions by the 5,000 to 8,000 U.S. troops and civilians who annually operate on the continent.

Africom and the Pentagon jealously guard information about their outposts in Africa, making it impossible to ascertain even basic facts — like a simple count — let alone just how many are integral to JSOC operations, drone strikes, and other secret activities. “Due to operational security, I won’t be able to give you the exact size and number,” Lt. Cmdr. Anthony Falvo, an Africom spokesperson, told The Intercept by email. “What I can tell you is that our strategic posture and presence are premised on the concept of a tailored, flexible, light footprint that leverages and supports the posture and presence of partners and is supported by expeditionary infrastructure.”

If you search Africom’s website for news about Camp Lemonnier, you’ll find myriad feel-good stories about green energy initiatives, the drilling of water wells, and a visit by country music star Toby Keith. But that’s far from the whole story. The base is a lynchpin for U.S. military action in Africa.

“Camp Lemonnier is … an essential regional power projection base that enables the operations of multiple combatant commands,” said Gen. Carter Ham in 2012, then the commander of Africom, in a statement to the House Armed Services Committee. “The requirements for Camp Lemonnier as a key location for national security and power projection are enduring.”

A map in the Pentagon report indicates that there were 10 MQ-1 Predator drones and four larger, more far-ranging MQ-9 Reapers based at Camp Lemonnier in June 2012. There were also six U-28As — a single-engine aircraft that conducts surveillance for special operations forces — and two P-3 Orions, a four-engine turboprop aircraft originally developed for maritime patrols but since repurposed for use over African countries. The map also shows the presence of eight F-15E Strike Eagles, manned fighter jets that are much faster and more heavily armed than drones. By August 2012, an average of 16 drones and four fighter jets were taking off or landing there each day.

Located on the edge of Djibouti-Ambouli International Airport, Camp Lemonnier is also the headquarters for Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA), which includes soldiers, sailors, and airmen, some of them members of special operations forces. The camp — which also supports U.S. Central Command (Centcom) — has seen the number of personnel stationed there jump around 450 percent since 2002. The base has expanded from 88 acres to nearly 600 acres and has seen more than $600 million already allocated or awarded for projects such as aircraft parking aprons, taxiways, and a major special operations compound. In addition, $1.2 billion in construction and improvements has already been planned for the future.

As it grew, Camp Lemonnier became one of the most critical bases not only for America’s drone assassination campaign in Somalia and Yemen but also for U.S. military operations across the region. The camp is so crucial to long-term military plans that last year the U.S. inked a deal securing its lease until 2044, agreeing to hand over $70 million per year in rent — about double what it previously paid to the government of Djibouti.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments