Labor union leaders and supporters are reaching out to working-class voters using a revised model for organizing after decades of legislative and legal defeats. It's an approach that union leaders believe can work to help return districts in many battleground states to Democratic control, which had previously voted for Trump. Core principles its favored candidates are highlighting include workplace regulation, expansion of healthcare, and reforming the nation’s tax code.

Working America, which is an AFL-CIO affiliate but not a labor union, works to connect with non-labor union members primarily through door-door contact, and has been canvassing heavily in up-for-grab areas like Ohio’s 12th congressional district, which includes parts of Columbus.

On Aug. 24, Republican Troy Balderson won a special election to fill the district's vacant House seat, but election officials took almost two weeks to declare him the winner since the final count was so close. The next election for the seat will be this November – and once again, likely too close to call until all the votes are tallied.

“You will be able to govern more (places) if you win in Ohio’s 12th,” Working America's director, Matt Morrison, told Occupy.com. Providing an overview of the group’s strategy, he said his organization targets winnable seats like this one by reaching out to working class voters. The goal is to turn these districts Democratic, or at least elect representatives who are receptive to traditional working class people's political demands.

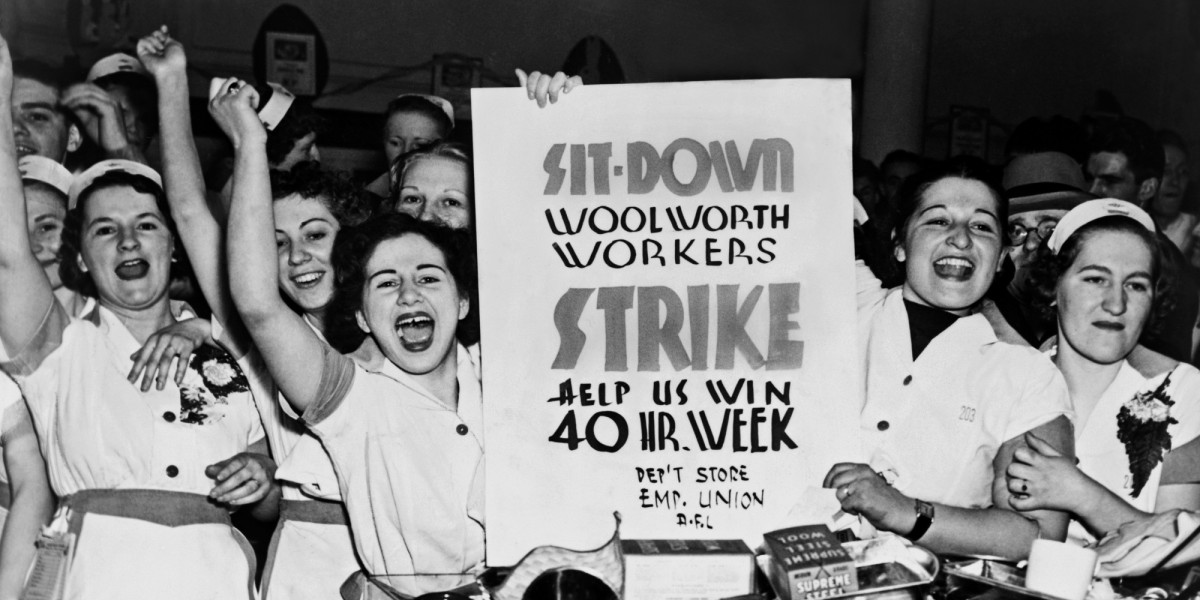

A half century ago, labor unions were a major force in American politics. Since 1983, the earliest year the Bureau of Labor Statistics has comparable data about union membership numbers, union members in the U.S. have declined by almost half. In Michigan, a bedrock of union membership, rates dropped from 20 percent of the population in 2005, to 15 percent just a decade later.

Even though union membership of public sector employees has increased since 1983, according to the bureau, unions – and in particular public sector unions – suffered a major defeat last June when the Supreme Court ruled that workers couldn't be compelled to pay union dues even if they benefitted from collective bargaining contracts.

“The larger context (of the labor union movement) is colored by the Supreme Court ruling, which has the labor movement reeling and in disarray," Susan J. Schurman, a professor of labor studies at Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations, told Occupy.com. (In 2012, Schurman mediated the merger between Hollywood’s two major actor unions, the Screen Actors Guild and the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists.)

Since the 2008 financial crisis and recession, right-to-work laws have expanded into West Virginia, Indiana and even into the birthplace of many aspects of the organized labor movement, Wisconsin. Missouri passed right-to-work legislation, but after a union-organized campaign brought the issue up for direct voter approval, voters rejected the law this summer.

Long-standing labor unions such as United Auto Workers and American Federation of Teachers have information on their websites to assist their members. Much of it focuses issues facing union members and steps members can take to make their voice heard, but it doesn’t outline how to attract more members or reach out to non-union labor.

In some cases, traditional labor unions like these have supported Republican congressional candidates in uncontested districts where they are supportive of at least some union positions. Repeated requests for interviews at both UAW and AFT went answered.

“There is a crisis inside organized labor…..the largest in my lifetime,” Schurman said regarding the unorthodox approach.

In Wisconsin, for example, labor’s political clout has been severely weakened by legislation since 2010 following a Republican resurgence that took control of the governorship and state legislature. The state has several elected offices up for vote this mid-term – including Governor Scott Walker – which could likewise impact unions' outlook.

Wisconsin remains a major battleground state for both parties. It is the state where the Populism movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries flourished and expanded onto the national scene. It is also the home state of infamous Senator Joseph McCarthy. Today, the state is about equally divided between Republicans and Democrats. Labor could play a major role in deciding the current election.

“Their (labor union) numbers are down but intensity is there,” Dr. David Canon, a professor of political science at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, told Occupy.com. “You see state legislature seats that flipped to Democratic in special elections that went for Trump.”

Wisconsin's controversial 2015 voter ID law could be a major factor this election. A study by another University of Wisconsin political scientist, Ken Mayer, found the law had already deterred 11 percent of voters – as many as 23,000 people – and disproportionately affected those with incomes of less than $25,000.

Groups like Working Americans are seeking to offset these changes by connecting with working-class individuals and reaching across racial lines. The organization has reached out to minority communities to energize them to vote in the mid-terms – seizing on an election cycle year when traditionally Democratic voters have turned out in lower numbers than Republicans. They are implementing a strategy different from the one used by the Clinton campaign in 2016.

“We wanted to go into areas where no (other progressives) and no one else was, then focus on issues,” Morrrison said. “They want to hear practical solutions on issues they care about, like healthcare. When we tell them something they didn’t know, they open up.”

Bringing union power back to its zenith of the 1950s and 60s is unlikely to happen anytime soon. But if the labor movement adapts to the changing economic and political realities that got Trump elected two years ago, it could play an outsized role helping to reshape the body politic as economic insecurity for the majority increases.

“Working people don’t have a choice,” Schurman said.