One of the highest-paid Chief Executive Officer's (CEO) in the United States runs a company most people have never heard of, and which has never turned a profit.

But those facts haven’t stopped Cheniere Energy’s board from awarding Charif Souki more and more money year after year.

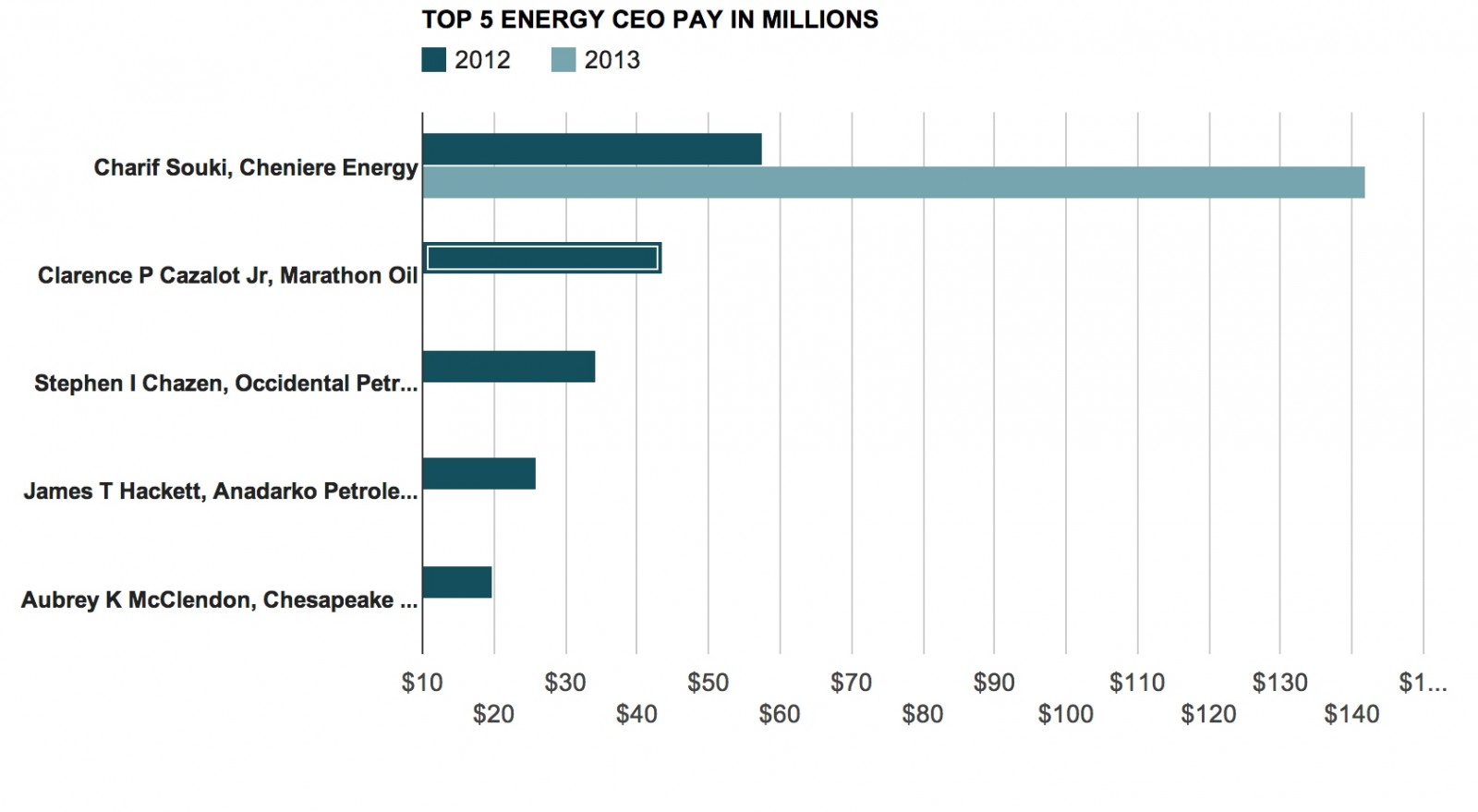

According to regulatory documents filed to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission this week, Cheniere more than doubled Souki’s take-home pay in 2013 to $142 million, dwarfing the compensation of other energy companies, even ones 50 times the size of Cheniere like ExxonMobil and Chevron.

While 2013's CEO compensation numbers for many companies aren't yet available, if they are similar to 2012's numbers, Souki could rank as the top-paid CEO in the U.S. (The higest paid CEO in 2012 was heath care giant McKesson's John H. Hammergren, at $131 million.)

Energy analysts say Souki’s compensation is uniquely puzzling, but may provide insight into how high a value Wall Street and politicians have placed on the hydraulic fracturing boom, and the possibility of exporting U.S.-produced gas to growing economies like China and India.

Cheniere’s main business for the past six years has been converting a natural gas import facility in Sabine Pass, Louisiana into a liquid natural gas (LNG) export facility. While the transition isn’t near completion, the Sabine facility is expected to be one of the first large-scale LNG operations capable of taking gas from new hydraulic fracturing boomtowns in places like Pennsylvania and Ohio, liquefying it, and shipping it across the world.

Many politicians and pundits have bet big on the idea that demand for natural gas in the developing world could create economic opportunity in the U.S. Some have even predicted that the current crisis in Ukraine would allow U.S. energy companies to undermine Russian gas giant Gazprom, and take control of the gas market in Ukraine and possibly much of Europe.

That idea could be part of the reason that Cheniere’s stock has doubled in the past year alone. And the astronomical rise of Cheniere’s stock accounts for most of Souki’s pay.

But analysts say that unfettered rise ignores several realities about the rocky past of Cheniere, and the potentially rocky future of liquid natural gas export.

“We’re still several years away from being an effective exporter of LNG, so to see him being rewarded for an industry that’s still on training wheels...it’s shocking,” said John Licata, the Chief Energy Strategist at commodities research firm Blue Phoenix. “It represents a success factor that has yet to materialize.”

Cheniere’s success comes as hydraulic fracturing, also known as fracking, has caused natural gas production across the U.S. to expand from about 19 million cubic feet in 2005 to about 25.5 million cubic feet in 2013, according to the Energy Information Administration.

The continued rise of fracking has led some to predict that the U.S. will eventually be able to export more gas than it imports. And Cheniere’s $12 billion Sabine Pass plant could be one of the largest facilities able to export that gas, starting as early as next year.

But Licata and other analysts say that might be putting the cart before the horse.

For one, the U.S. still doesn’t have free trade agreements with China, India, or many other countries where companies like Cheniere are hoping to export to. There’s no guarantee agreements will be set up before the proposed opening date of Sabine Pass.

Other technologies, like floating LNG facilities that can move around the world, might undercut the need for LNG facilities like Sabine, Licata said.

And even if newer technology doesn’t disrupt the potential dominance of Sabine Pass, some energy analysts, like independent oil and gas researcher Arthur Berman, think the natural gas boom in the U.S. has been greatly overstated.

Berman says you don’t need to look any further than Cheniere’s own history to see that predictions about natural gas are often wildly off-base.

Cheniere spent years and billions of dollars building Sabine Pass as a natural gas import facility. But then the U.S. gas boom began, and in order to save its business Cheniere began converting Sabine Pass into an export facility. Berman says if Cheniere and U.S. analysts were wrong about the need for an import facility prior to 2008, what’s to say they’re not just as wrong about the need for an export facility now?

“We’ve just completely gotten LNG wrong for the last several decades,” Berman said. “(Cheniere) is a company that has lost vast amounts of money betting wrong on LNG imports... so I was shocked to find out that the CEO of a company that’s never made any money makes more than anyone else in the industry.”

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments