New York City police have tracked citizens’ cellphones over 1,000 times since 2008 without using warrants, according to public records obtained by the New York Civil Liberties Union.

The organization announced Thursday that the NYPD has typically used “stingrays” after obtaining lower-level court orders, but not warrants, before using the devices. The department also does not have a policy guiding how police can use the controversial devices. This is the first time that the scope of stingray use by the nation’s largest police agency has been confirmed.

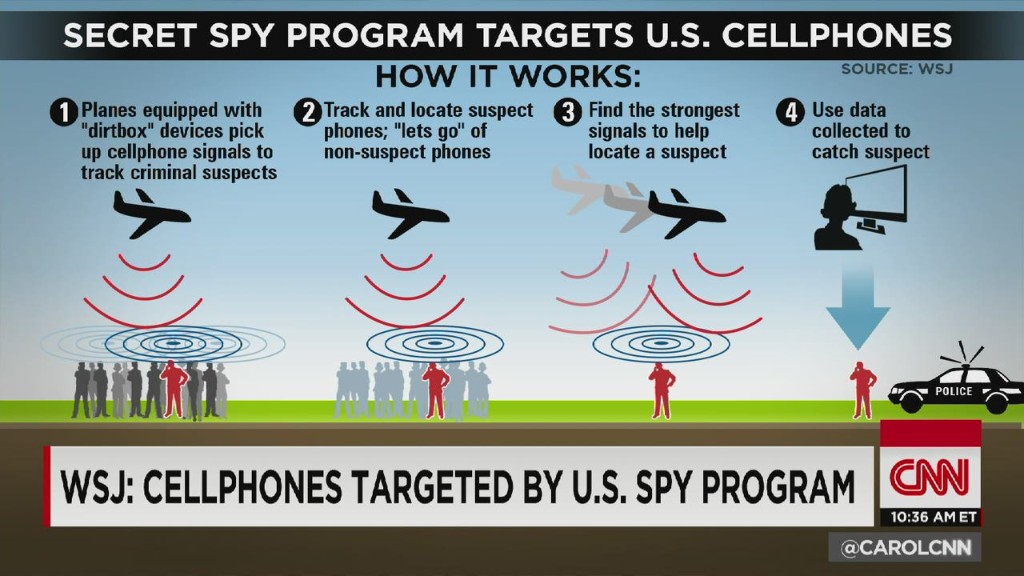

The devices, generically known as stingrays, work by mimicking cell towers and tracking a cellphone’s location at a specific time. Law enforcement agencies can use the technology to track people’s movements through their cellphone use.

Stingrays can also detect the phone numbers that a person has been communicating with, according to the NYCLU. The devices allow law enforcement to bypass cellphone carriers, who have provided information to police in the past, and can track data about bystanders in close proximity to the intended target.

Mariko Hirose, the NYCLU attorney who filed the records request, said the records reveal knowledge about NYPD’s stingray use that should have been divulged before police decided to start using them.

“When local police agencies acquire powerful surveillance technologies like stingrays the communities should get basic information about what kind of power those technologies give to local law enforcement,” Hirose said.

The records show that the devices were used in a range of crimes, including rape, murder and missing persons cases. They detail which NYPD squads used Stingrays, the target’s cellphone carrier, and whether the investigation resulted in an arrest.

Information about the exact date that stingrays were used, the target’s phone number and any subsequent arrest locations were redacted. The NYPD did not release information about which types of stingrays the department uses or contracts related to the purchase of the devices. Hirose said the NYCLU has not decided if it will pursue the remainder of the request in court.

The devices are used across the country by federal and local law enforcement agencies, which go to significant lengths to hide stingray use. Last year, the Department of Justice released new policies about how federal agents could use the technology, requiring them to obtain a warrant except in exceptional circumstances.

The NYPD did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

*

MEANWHILE, Eva Galperin and Danny O'Brien report for Electronic Frontier Foundation that the U.K.'s Investigatory Powers Bill contains loopholes within loopholes that will lead to unbridled surveillance across the Atlantic:

The U.K. House of Commons Science and Tech Committee has recently published its report on the draft Investigatory Powers Bill, influenced by comments submitted by 50 individuals, companies, and organizations, including Electronic Frontier Foundation. The report is the first of three investigations by different Parliamentary committees. While it was intended to concentrate on the technological and business ramifications of the bill, their conclusions reflect the key concern of lawmakers, companies, and human rights groups about the bill’s dangerously vague wording.

The Investigatory Powers Bill, as written, is so vague as to permit a vast range of surveillance actions, with profoundly insufficient oversight or insight into what Britain’s intelligence, military and police intend to do with their powers. It is, in effect, a carefully-crafted loophole wide enough to drive all of existing mass surveillance practice through. Or, in the words of Richard Clayton, director of the Cambridge Cloud Cybercrime Centre at the University of Cambridge, in his submissions to the committee: “the present bill forbids almost nothing... and hides radical new capabilities behind pages of obscuring detail.”

The bill is 192 pages long, excluding over 60 pages of explanatory notes. Our comments to the committee focused on just one aspect of the bill, what they call “equipment interference.” Despite our emphasis on just one small part of the bill, our analysis revealed multiple ambiguities and broad new powers that would allow the security and intelligence agencies, law enforcement and the armed forces, to target electronic equipment such as computers and smartphones in order to obtain data, including communications content.

The bill also provides for the U.K. government to compel companies and individuals to comply with its surveillance demands, including those located outside Britain, and to bar companies from revealing that they were the subject of such demands. As the committee says in its conclusions, “We believe the industry case regarding public fear about ‘equipment interference’ is well founded.”

The bill also includes a new mandate for data retention whose breadth is similarly ambiguous. Terms like “internet connection records,” “telecommunications service,” “relevant communications data,” “communications content,” “technical feasibility,” and “reasonable practicable” were all criticized in the report for their vague and overbroad use. The government’s excuse is that it wants to create a “future-proof” bill, but loose language is bad for businesses trying to understand what obligations they are under. And it’s certainly bad for civil liberties when governments exploit those ambiguities to obtain or hold onto new powers.

The details of these definitions and safeguards surrounding them should not be punted into secondary legislation. As the committee notes, a disturbing degree of detail about the Investigatory Powers Bill is deferred to future “Codes of Practice.” We’ve been down this road before in the U.K. IPB’s predecessor, the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (2000) also placed its devilish details into future statutory instruments, which were often slipped past Parliamentarians with little warning or debate. The result was years of expansion of RIPA powers, to the point where powers originally intended for the intelligence services were delegated to over four hundred public bodies. Even the head of MI5, Lady Manningham-Buller, who lobbied for the RIPA powers, was shocked by the eventual overreach:

I can remember being astonished to read that organizations such as the Milk Marketing Board, and whatever the equivalent is for eggs, would have access to some of the techniques. On the principle governing the use of intrusive techniques which invade people's privacy, there should be clarity in the law as to what is permitted and they should be used only in cases where the threat justified them and their use was proportionate.

This is why, as the committee says, “it is essential that this timetable does not slip and that the Codes of Practice are indeed published alongside the Bill so they can be fully scrutinized and debated.”

We would go further: EFF believes that a productive discussion around the Investigatory Powers Bill can only begin once all the cards are on the table. The U.K. government needs to answer all the questions raised by the committee, including those currently postponed to Codes of Practice, and embed those answers in a revised bill, which can then be more seriously considered, or it's destined for a future of abuse followed by dismantlement in the courts.

The series of successful challenges in the U.K. and E.U. against previous surveillance law and practice shows that vague and unbounded language cannot survive a serious challenge in the courts. If the U.K. government wants its surveillance rules to stand the test of time, it needs to build them on a firm foundation of clarity, necessity, and proportionality.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments

Comments

Larry replied on

Stingray Surveillance

The use of this technology without first obtaining a warrant is absolutely unconstitutional as a form of "mass" warrantless searches as provided under the holding and rationale of the recent unanimous U.S. Supreme Court decision: Riley v. California, 134 S. Ct. 2473 (2014), slip opinion available at, http://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/13pdf/13-132_8l9c.pdf.

Stingray technology not only picks-up phone conversations and GPS-location data, but the newer versions can also suck-up into the police databases your contacts, internet searches and sites visited, as well as text messages.

To get a greater sense of the magnitude of what we're facing, take a look at the recent ground-breaking documentary "Killswitch" at the site: www.killswitchthefilm.com. The site is designed to enable the viewer to "Do Something" about the problem.