President Trump, before speaking on tax reform in St. Louis, Missouri. KEVIN LAMARQUE / REUTERS

One year ago, when Donald Trump signed into law the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, he boasted, “Everything in here... is really tremendous things for businesses, for people, for the middle class, for workers. And I consider this very much a bill for the middle class and a bill for jobs.”

But on the 1-year anniversary of the law, while reports indicate jobs and wage growth have increased across the board, that growth has been uneven as the majority of gains have gone to millionaires, billionaires and multi-billion dollar corporations.

The law reduced income tax rates for most, but the biggest gains went to the wealthiest. The cuts increased the after-tax income of those in the top 5 percent of income earners more so than the rest of income earners. At the same time, the tax cuts for most individual income earners will expire in 2025 while the corporate tax cut extends to 2027.

Proponents of the tax cuts pronounced its benefits, especially the extra money it would provide in paychecks. House Speaker Paul Ryan made a well publicized gaffe when he sent out a now-deleted tweet about a teacher in Pennsylvania getting $1.50 in extra take home pay.

But independent analyses like this June 2018 report from the Tax Policy Center paint a different picture. “The new law will reduce federal revenues by significant amounts, even after allowing for the modest impact on economic growth. It will make the distribution of after-tax income more unequal... raise federal debt, and impose burdens on future generations," the report said.

"If it is financed with spending cuts or other tax increases, TCJA will, under the most plausible scenarios, end up making most households worse off than if it had not been enacted."

The most recent Bureau of Labor Statistics report shows wage growth around 3 percent. For a hypothetical Pennsylvania teacher whose salary is $55,000, that teacher’s pre-tax and pre-deduction income has increased over the last year by just $31 a week.

Wage growth rate has held steady since the 2008 recession, but has not significantly increased since the tax cut legislation in 2017. Gains haven’t been equally distributed across industries.

A Bureau of Labor Statistics report in August showed higher wage growth in some industries such as bank tellers and retail. But as "Marketplace” reported, those increases were in part due to increased demand but also increases in the minimum wage. Eighteen states increased their minimum wage in 2018. Higher paying jobs such as web designers or physical therapists have actually seen a decrease in wage growth.

Two other discouraging signs from the last year include an increase in the under-employment figure for November, and the number of individuals who haven’t see a raise this year. BLS data shows the under-employment rate – the figure of those who are working part-time but seeking full-time work, or workers who stop actively looking for work – has grown this year. This helps explain why most workers have not gotten a raise.

A recent “Bankrate” survey found a majority of American workers did not receive a pay raise this year. Sixty-two percent of workers neither saw a raise in their own jobs nor as a result of transferring to a new job – an increase from the year before.

One result of the tax cuts legislation has been an increase in the nation’s deficit. The deficit, an obtuse and abstract problem for many, is when the national treasury pays more than it receives, adding to the nation’s debt. The amount of debt that is healthy for a nation is a contentious debate, but a higher debt burden can cripple an economy; the burden of paying it can fall on future generations who weren't responsible for accumulating it in the first place.

As the Baby Boomer generation ages in the coming years, less money will be paid into the treasury and more will have to be spent to care for an ageing population, including in healthcare costs. The nation’s infrastructure, which remains neglected, must be addressed and the failure to do so will lead to even greater costs down the road.

Meanwhile, in the last year, CEO pay has risen 17 percent after two years of relative modest growth, according to the non-partisan Economic Policy Institute. CEO-worker pay disparity was 20 to 1 in 1965, an era of a prosperous American middle class. In 2017, the ration was 300 to 1, the highest since before the 2008 recession.

“Skyrocketing CEO pay is not a reflection of the market for executive talent,” EPI analyst Jessica Schieder said. Instead, CEOs are able to take advantage of generous stock options that make up their compensation.

The EPI report concludes that if CEOs were taxed higher or earned less, there would be no reduction in productivity or employment.

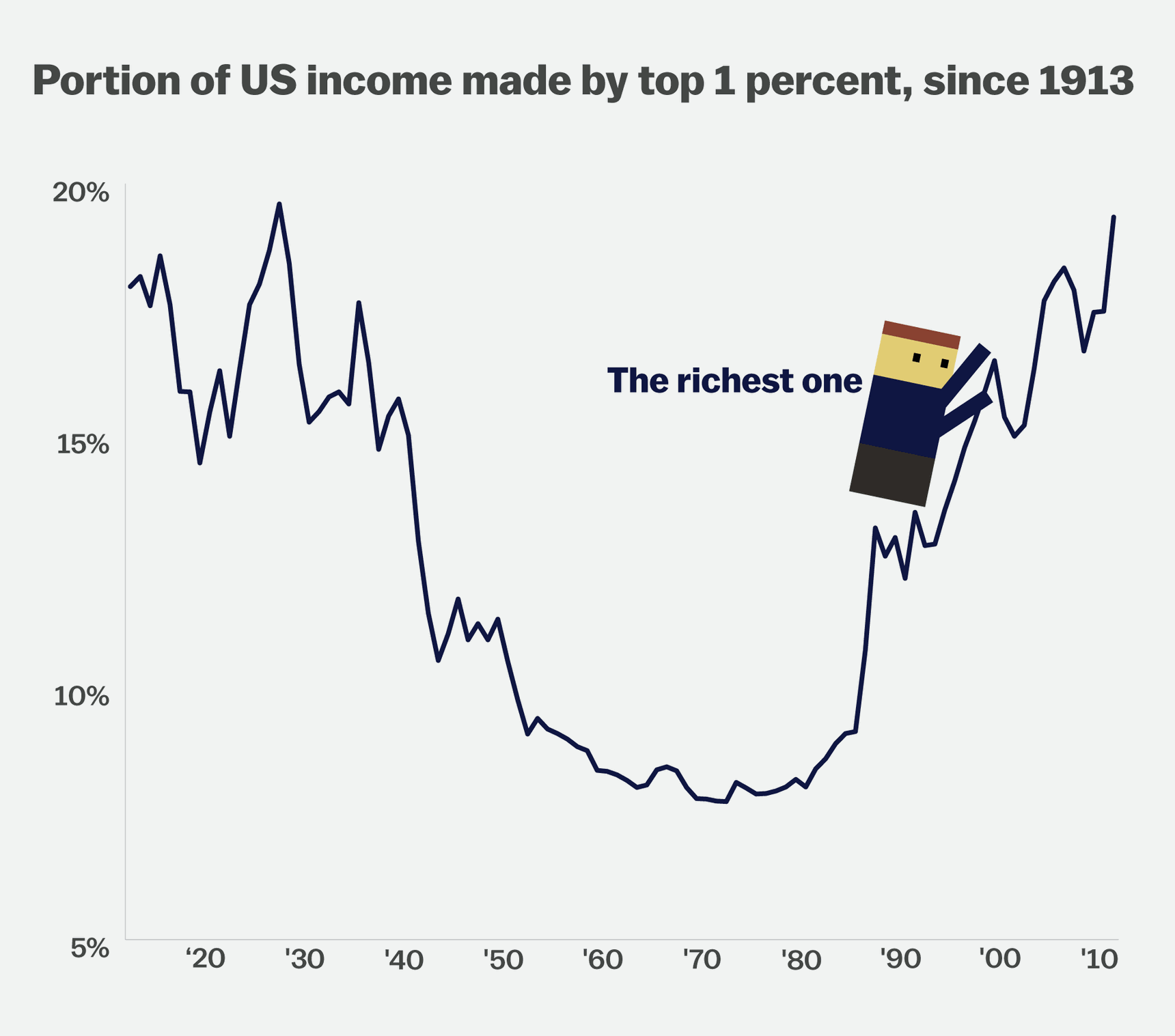

The House of Representatives will switch party control in January, but the Senate and the presidency remain in Republican control, making any revision of the tax legislation unlikely. Most of the provisions of the legislation continue through 2025, but just one year after the legislation there are signs of growing wealth inequality, even increasing to the level just prior to the Great Recession.