For at least the last 800 thousand years, until the early 1800s, the baseline for carbon dioxide in the air was 250 parts per million, or PPM. It's a measurement of the number of molecules of carbon dioxide after the water vapor is removed. This figure is not contested and is arrived at with the use of relatively simple technological tools.

In 2015 the PPM for carbon dioxide is about 400. The rise since 1850 has been more than steady; it's been an exponential curve, meaning that the number increases more rapidly mathematically over time. Think compound interest on money in the bank, if you have any. Its increase is an exponential curve.

Given the gap between 250 PPM in the mid-1800s and 400 PPM today, a reasonable question might be, When did Earth last have air with the larger amount of CO2 in it? There is no simple, agreed-upon answer. But research at places like the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, and direct evidence from air bubbles in ice cores drilled in Antarctica, are clear about one thing: it was long time before Homo sapiens were around.

The journal Science puts the likely date back in the Miocene epoch. That's 10 to 15 million years ago, about 40 million years after the dinosaurs got wiped out by a bolide angling through the atmosphere and hitting Earth like a bullet the size of Mt Everest. If you like it hot, the Miocene was the epoch for you. You would have seen critters you recognize, too, like cats, raccoons, camels, rhinos, and our ancestors the great apes, along with mastodons who liked chasing them down.

There were crows cawing in the trees, grass lands blowing in the breeze, especially as the epoch came to an end. Overall, though, it was hot. Climate scientist Michael Mann described the Miocene as "a time when global temperatures were substantially warmer than today, and there was very little ice around anywhere on the planet... sea level was considerably higher – around 100 feet higher – than it is today."

Today, the amount of carbon dioxide in the air is like it was then, and rising fast. But the effects of the warmth caused by greenhouse gases take years, decades and centuries to accumulate, gradually changing everything we tend to think of as fixed – like the white crown of Mt. Kilimanjaro (in the last 100 years about 85 percent of the mountain's ice and snow cap has disappeared), and the Mer de Glace, or Sea of Ice, on the slopes of Mont Blanc (the largest glacier in France, its ice has decreased in thickness about one meter per year since 1985).

The baseline change of carbon molecules in the atmosphere is the root cause of such phenomenon. And the negotiations to do something about it in Paris will only impact the future, not recapture the past.

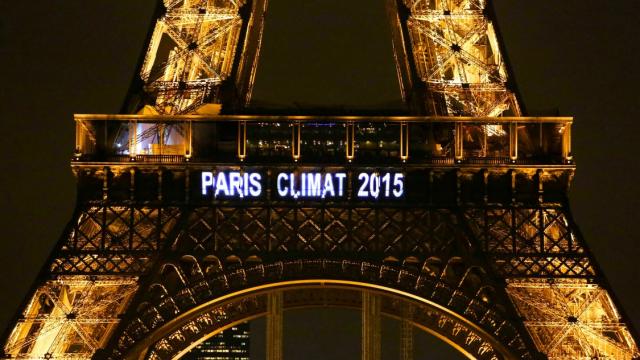

The goals of COP21 are low. They aim for politically feasible while being environmentally rather pathetic. The French philosopher and economist Maxime Combes said right before the conference opened that even the best deal possible from the negotiations "will be light years away from should be achieved."

On the third day of the conference, James Hanson, the renegade American scientist who forewarned the U.S. Congress back in 1988 about the looming threat of atmospheric warming, agreed. Hanson called the impending deal "half-assed and half-baked." His argument is that there is no way that the tentative plans to put the lid on a global temperature rise of less than 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F) is going to happen. Yet if that does not come about, the growing consensus of the science world can be summarized by one word: catastrophe.

COP21 supporters and critics of all stripe love to attack Hanson. Now a 74-year-old activist, the former head of the Goddard Institute is used to it. Critics of Hanson should recall what Michael Mann said two years ago, when the CO2 load was only approaching the 400 PPM mark: "There is the possibility that we’ve already breached the threshold of truly dangerous human influence on our climate and planet."

In the global slugfest going on now in Paris over feasible outcomes and future dangers, the relevant number to remember is 400 PPM of carbon now being in the air. Not just because it's a level that hasn't been in the sky since before humans arrived, but because of what it means for the oceans. They warm faster than air. A lot faster.

Our five oceans – the Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, Arctic and Southern – have an ability to store heat in the deep that is approximately a thousand times that of the atmosphere. You need to remember that the two combine to make our biosphere, which is symbiotic, complicated and beautiful beyond our ability to comprehend – or has been, until we screwed up the dynamics like we did.

At this chapter in the climate change story, and the COP21 negotiations, we understand minimally about how the oceans work as carbon sinks, as Earth's main thermostat, as a sustainable environment for plankton which feed countless sea creatures and make up 95 percent of all marine biomass, and as a gigantic carbon pump which basically is a god-like natural machine that rules our future. In other words, science has a lot to learn, never mind convince the earth-is-flat group to listen.

Returning to baselines and the last epoch in which the baseline was the same 400 PPM we have now, the question is, Can humans survive another Miocene? Most likely, yes. The air at that time sustained mammals with lungs like ours, biology we harbor in our flesh. There was fresh water. There was game to hunt, fruit to pick, fish to catch. The Miocene epoch might not have been so bad, actually.

But we weren't there. And it was a bit short on human comforts and civilization.

We are here. Now. Struggling in Paris with the future of the planet. And our old, long-time comfortable baseline for carbon in the air is toast. It's history. And its replacement isn't a line at all. It's an ever steeper upward slope with an exponential curve. Since the Industrial Revolution began, the curve has gotten steeper because the burning of fossil fuels, which are carbon stored in the ground, energized modern life and convinced us that we're lords over this spinning globe's domain. That attitude, though, seems shaken.

COP21 is more serious than its predecessors. All the glacial melt, specie die offs, weather disasters, and on and on have folks from Baffin Island to Cape Fear worrying. They know that the baseline for carbon dioxide in Earth's air has, as Mann said, been breached. They want politicians to do something about it.

We'll all have to stay tuned to learn what the outcome of COP21 will be in both the short frame, next week, and the long one, the next few years. Over 170 nations sent in individual plans about when they will peak their respective carbon outputs. Or try to, though not commit to. Meanwhile, the shadow of eventual extinction looms over Paris, terrorism worries smother public freedom, and protesters in the city find themselves under house arrest. It doesn't feel like the authorities want the public to visit the conference site, though that may change on the second week.

It's not the greatest atmosphere for progress. But the pressure to do something big and meaningful is intense. The proposals now on the table are not capable of halting the temperature rise at 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F) – not unless a lot of the nations, with the big carbon emitters like the U.S., China and the members of the E.U. leading the way, ratchet up their carbon-capture methods and seriously reduce their emissions.

Alas, the mood at the side events in Paris often mirrors that of the scientific consensus: that the deal is made to fail. We're all going over the falls. And no amount of back paddling will change that. The end of this century will see a temperature uptick above 2 degrees C, without a show of will and action the magnitude of which the nations of the world have as of yet failed to deliver.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments