This is the second part of a WashPo investigative series on aggressive police. The first part appeared here.

During the rush to improve homeland security a decade ago, an invitation went out from Congress to a newly retired California highway patrolman named Joe David. A lawmaker asked him to brief the Senate on how highway police could keep “our communities safe from terrorists and drug dealers.”

David had developed an uncanny talent for finding cocaine and cash in cars and trucks, beginning along the remote highways of the Mojave Desert. His reputation had spread among police officers after he started a training firm in 1989 to teach his homegrown stop-and-seizure techniques. He called it Desert Snow.

The demonstration he gave on Capitol Hill in November 2003 startled onlookers with the many ways smugglers and terrorists can hide contraband, cash and even weapons of mass destruction in vehicles. It also made David’s name in Washington and launched his firm into the fast-expanding marketplace for homeland security, where it would thrive in an atmosphere of fear and help shape law enforcement on highways in every corner of the country.

Over the next decade, David’s tiny family firm would brand itself as a counterterrorism specialist and work with the departments of Homeland Security and Justice. It would receive millions from federal contracts and grants as the leader of a cottage industry of firms teaching aggressive methods for highway interdiction. Along the way, working in near obscurity, the firm would press the limits of the law and raise new questions about police power, domestic intelligence and the rights of American citizens.

In 2004, David started a private intelligence network for police known as the Black Asphalt Electronic Networking & Notification System. It enabled officers and federal authorities to share reports and chat online. In recent years, the network had more than 25,000 individual members, David said.

“Throughout history law enforcement investigations have been stymied because of law enforcement’s inability to move information and because enforcement entities refuse to work together,” David wrote in a 2012 letter to Black Asphalt members that was obtained by The Post. “This website allows all of us to do that.”

Operating in collaboration with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, Immigration and Customs Enforcement and other federal entities, Black Asphalt members exchanged tens of thousands of reports about American motorists, many of whom had not been charged with any crimes, according to a company official and hundreds of internal documents obtained by The Post.

For years, it received no oversight by government, even though its reports contained law enforcement sensitive information about traffic stops and seizures, along with hunches and personal data about drivers, including Social Security numbers and identifying tattoos.

Black Asphalt also has served as a social hub for a new brand of highway interdictors, a group that one Desert Snow official has called “a brotherhood.” Among other things, the site hosts an annual competition to honor police who seize the most contraband and cash on the highways.

As part of the contest, Desert Snow encouraged state and local patrol officers to post seizure data along with photos of themselves with stacks of currency and drugs. Some of the photos appear in a rousing hard-rock video that the Guthrie, Okla.-based Desert Snow uses to promote its training courses.

Annual winners receive Desert Snow’s top honorific: Royal Knight. The next Royal Knight will be named at a national conference hosted in Virginia Beach next year in collaboration with Virginia State Police.

In just one five-year stretch, Desert Snow-trained officers reported taking $427 million during highway encounters, according to company officials. A Post analysis found the training has helped fuel a rise in cash seizures in the Justice Department’s main asset forfeiture program.

In January last year, David hired himself and his top trainers out as a roving private interdiction unit for the district attorney’s office in rural Caddo County, Okla. Working with local police, Desert Snow contract employees took in more than $1 million over six months from drivers on the state’s highways, including Interstate 40 west of Oklahoma City. Under its contract, the firm was allowed to keep 25 percent of the cash.

When Caddo County District Court Judge David A. Stephens learned that Desert Snow employees were not sworn law enforcement officers in Oklahoma, he denounced the arrangement as “shocking,” and he threatened to put David in jail if it continued.

The state’s American Civil Liberties Union chapter called for an investigation of the district attorney and criminal charges against Desert Snow employees for impersonating law enforcement officers.

“Desert Snow. It sounds like a covert military operation or a street name for designer cocaine. Truth be told, it’s something much more sinister in my modest opinion,” Oklahoma defense attorney Adam Banner wrote in a legal blog, adding that it “seems to amount to little more than a free-for-all cash grab.”

District Attorney Jason Hicks set aside more than a dozen convictions relating to the seizures and promised a review. He said he was just trying to offset the loss of federal funding for a drug task force.

“I fully believe we are in compliance with state law and, at the time the program was formed, my intent was to see that my investigators received top-notch training and to ensure that we could continue the operation of the drug and violent crime task force,” Hicks said.

David A. Harris, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh Law School, said highway interdiction now “works just like all the drug interdiction efforts” in the 1990s. “But the focus is on money,” he said. “That makes it all the more insidious.”

Desert Snow officials in interviews disclaimed the practice of targeting drivers for money, sometimes known as “policing for profit.” They said that seizing cash is a proven tool for hurting drug and crime organizations.

But privately, they promote a book that extols the quest for cash. Ron Hain, a marketing official with Desert Snow and a full-time deputy sheriff in Kane County, Ill., has urged police to use cash seizures to bolster municipal coffers.

“In Roads: A Working Solution to America’s War on Drugs,” a book Hain self-published under the pen name Charles Haines in 2011, states that departments can “pull in expendable cash hand over fist.”

The firm defends its training as first-rate, and David once likened the firm’s students to special forces operators. “Like the SEAL team, Army Rangers or any other top notch outfit it requires commitment and perseverance to be part of ‘the team,’ ” David wrote in a sales pitch posted on Black Asphalt.

Desert Snow officials have taken pains to ensure that Black Asphalt complies with all laws and that its site is securely encrypted, David wrote in his 2012 letter to the membership. He said the system does not store any sensitive information about drivers but only passes it along to law enforcement. Only “certified peace officers” can access the system.

After questions arose several years ago about the system’s private ownership, David transferred authority to the sheriff’s office in Logan County, just north of Oklahoma City.

David said that more than 16,000 “major incidents” had been reported through the system, leading to hundreds of follow-up investigations, arrests and seized assets.

“Over the years I have also received phone calls and letters of gratitude from all levels,” David wrote in 2012. “I have even met with federal people in both Washington D.C. and elsewhere regarding the website and have even received financial contributions for the Black Asphalt from District Attorneys, agencies and federal entities.”

DHS spokeswoman Marsha Catron downplayed the department’s involvement, saying in a statement that it has awarded “Desert Snow less than 20 contracts since 2008 for specialized law enforcement training and educational services.” That includes three contracts this year worth more than $268,000 with Customs and Border Protection, one of them in August.

Catron defended the use of Black Asphalt. “The network simply allows law enforcement officers to alert fellow agencies about seizures that have been made,” her statement said. “Participation in this network by state, local or federal agencies is voluntary. This kind of networking allows law enforcement agencies to develop leads, corroborate investigative information and aids in the pursuit of criminal enterprises.”

She said that Black Asphalt reports no longer contain any personally identifiable information about drivers.

DEA spokesman Rusty Payne said that computers at the agency’s El Paso Intelligence Center (EPIC) once housed Black Asphalt. In a subsequent e-mail, Payne said that agents only used it as a source of information. “We would go in there to grab information,” he said.

Payne also told The Post that the DEA had recently stopped using Black Asphalt reports because of concerns that they “would never hold up in court.”

Payne said officials at Justice and DEA are now reviewing their use of the system. However, as recently as May, internal Black Asphalt records continued to list officials at the agency, along with officials at DHS, CBP and ICE, as members.

The Start of Desert Snow

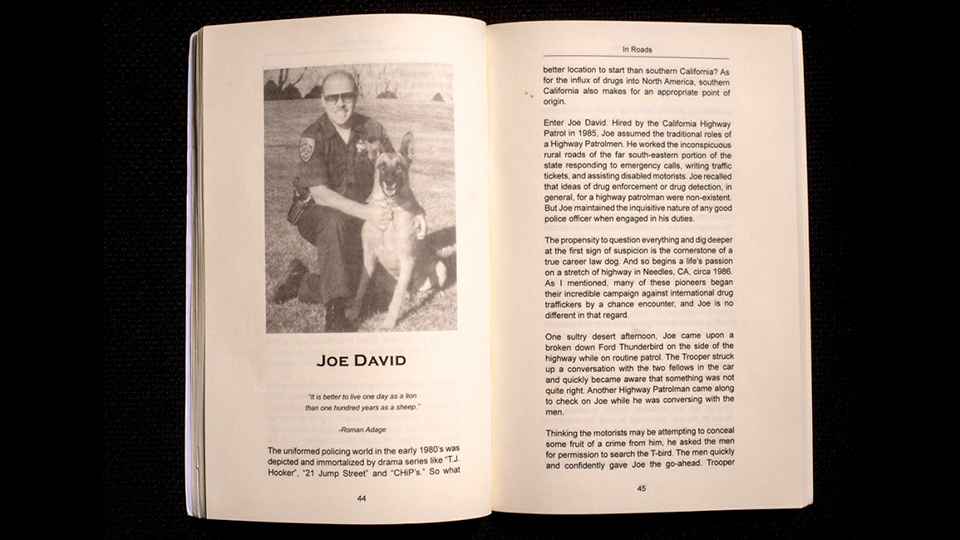

Joe David, 61, did not respond to multiple requests for an interview. This account is based on interviews with two Desert Snow officials and more than a dozen current and former members of the Black Asphalt network, along with hundreds of internal documents, legal records and the account given by Hain in “In Roads.”

David married as a teenager, started a family and worked his way up from the road patrol. He was smart and gregarious, with a close-cropped haircut and a special way with the drivers he encountered.

His career began on the hard-baked desert highways of southeast California, where he was assigned soon after joining the California Highway Patrol in 1985. From the start, he was intrigued by the cat-and-mouse game with smugglers. One day, he was driving through Needles, Calif., not far from the Arizona border, when he saw a Ford Thunderbird on the side of the road. The driver and passenger struck David as suspicious. Though he had no evidence of a crime, he asked whether he could search the car.

The driver agreed but David’s search was turning up blank — until an old school acquaintance drove up and stopped to watch. The classmate happened to be an automobile upholsterer. David asked him to look at the car and see if anything was amiss in the interior. The classmate spotted an irregularity in the sewing on the seats. Hidden underneath was 44 pounds of cocaine.

David was hooked on interdiction. Year after year, he made big seizures. He once found 2,500 pounds of cocaine in a box truck, worth more than $22 million. “Trooper David became a one-man wrecking ball, and terrorized members of drug cartels for years to come,” Hain wrote.

David earned the nickname “Canine,” and he claimed that he could smell cocaine concealed among other odors, like detergent, court records show.

He began moonlighting as a personal instructor for police who found the prospect of highway interdiction exciting and useful. He started in the late 1980s with informal tutorials over backyard barbecues and later moved the sessions into the family garage.

Today, Desert Snow is still a family business that employs his wife and children.

From the beginning, David lectured about the damage drugs do to communities and portrayed his students as soldiers on the front lines of a war.

“These pioneers realized there is one vital course of action for the local police officer to begin conquering our nation’s continuing battle: knowledge, training in profiles, and the relentless pursuit of narcotics smugglers,” Hain wrote.

Facing Scrutiny

In the early 1990s, as he took on teaching assignments during breaks from his day job, David’s reputation grew. Soon, he was teaching local police for the DEA’s El Paso Intelligence Center, a clearinghouse for information about drug smugglers and their associates. He also taught for the Drug Interdiction Assistance Program at the Department of Transportation, which focuses on commercial vehicle safety.

But his methods came under scrutiny in court. In July 1993, David stopped a man driving a half-ton pickup with tinted windows on Interstate 40 near the California-Arizona border. He asked the driver, a Hispanic man, to roll down the window and hand over his license and registration.

David said he thought the driver was suspiciously nervous and he thought he smelled cocaine though the open window, according to court records. David was by now a canine officer, but he didn’t have his dog with him that day.

He told the driver to stand on the side of the road and began conversing with him.

David eventually told the driver that he was convinced there was a large of amount of cocaine in the truck and asked for permission to search. The driver was reluctant, but he eventually signed a bilingual form giving consent. David found more than 40 pounds of the drug.

At a court hearing, the driver’s attorney unsuccessfully argued that the evidence should be suppressed because it was obtained through intimidation. David responded that he behaved appropriately. Prosecutors said he spoke “without coercion in a low-key conversational tone.”

But a three-member federal appeals court ordered a new trial for the driver, saying David overstepped his authority to obtain approval for a warrantless search.

“Officer David persisted in his ‘low key’ questioning until he got the answer he sought,” the court’s ruling said. “Such persistent questioning is characteristic of a stationhouse interrogation.”

The court ruled that David had improperly detained the driver without arresting him. The court did not specify how long he kept the driver on the roadside, but it said David should have given the driver a Miranda warning that he had a right to remain silent after David concluded he was going to arrest him.

“It takes 30 seconds to give Miranda warnings,” the court said. “Officer David delayed giving Miranda warnings in order to subject [the driver] to psychological pressure to make incriminating statements. That was a blatant Miranda violation.”

“Miranda warnings are intended to deter precisely the sort of conduct engaged in by Officer David: isolation, psychological pressure, and relentless pursuit of a confession,” the court said.

Desert Snow would adopt “Relentless Pursuit” as the firm’s motto.

By the late 1990s, David also participated as an instructor in Operation Pipeline, a highway interdiction program run by the DEA that trained nearly 27,000 police in 48 states over more than a decade. The program encouraged the same sorts of techniques that David had long employed on his own: high volumes of stops for minor traffic infractions and conversations with drivers to look for inconsistencies and obtain permission for warrantless searches.

David received acclaim for a Pipeline stop of a truck-trailer in 1998. Pulling the vehicle over on a minor infraction — straddling two lanes — David and his partner found 720 pounds of marijuana.

About the same time, Democrats in the California statehouse formed a task force to investigate claims that Operation Pipeline was profiling Hispanic drivers.

“Pipeline teams are able to pull over a great many cars to find drivers who fit established ‘profiles,’” the task force report said. “If a motorist ‘fits’ the profile, then the officer’s goal becomes to conduct a warrantless search of the car and its occupants, in the hope of finding drugs, cash and/or guns.”

The ACLU found that the majority of those stopped nationwide by interdiction programs such as Operation Pipeline were minorities, according to a 1999 report titled “Driving While Black.”

“All the evidence to date suggests that using traffic laws for non-traffic purposes has been a disaster for people of color,” said the report, written by Harris, the University of Pittsburgh law scholar. “Law enforcement decisions based on hunches rather than evidence are going to suffer from racial stereotyping, whether conscious or unconscious.”

The ACLU filed a class-action lawsuit over such stops, and in 2003 the California Highway Patrol settled, paying $875,000 and agreeing to provide additional training for officers but admitting to no wrongdoing.

That year, David retired and began ramping up Desert Snow. The new Department of Homeland Security was forming and a new market was opening up in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

The invitation from Sen. Charles E. Grassley (R-Iowa) in the fall of 2003 paved the way for David and Desert Snow. David took a tractor-trailer to Capitol Hill, where he surprised lawmakers and Capitol Police by revealing myriad cubbyholes for hiding contraband. Once he would have focused on drugs and money. Now he emphasized that the hiding places could be used by terrorists.

Funding for Desert Snow soon came from DHS, which provided a grant to help the firm tailor its instruction to counterterrorism. Over the years, the firm has received scores of contracts from DHS, Justice and other federal agencies worth more than $2.5 million. States and localities also have used homeland security grants and seized cash to pay for classes from Desert Snow and its competitors.

In 2004, one of the main thrusts of the homeland security efforts was to connect the dots of potential threats through information-sharing. Officials at ICE also began working with the DEA on an initiative to fight cash smuggling through better intelligence and collaboration with local and state police. The effort was framed as a fight against terror financing.

“To address this increasing threat, the DEA, IRS [Criminal Investigation] and ICE are working together to initiate a bulk currency program to coordinate all U.S. highway interdiction money seizures,” DEA Administrator Karen Tandy told a Senate panel.

That year, David launched Black Asphalt.

Run as a private adjunct to the for-profit Desert Snow, Black Asphalt’s goal was to enable highway patrolmen in different states to informally share information about drivers as quickly as possible. David has said he saw the need for such a system when he was a Pipeline instructor and noticed that only a quarter of the highway stops were being reported to anyone. Such information could be valuable to the DEA’s El Paso Intelligence Center and the 28 federally supported High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas (HIDTA) task forces across the nation.

“The Black Asphalt was designed to support EPIC, HIDTA and other government programs,” David wrote in his 2012 letter to the membership.

Black Asphalt soon attracted thousands of members from across the country. One lauded feature of the site is an extensive “concealment database” of hiding places in vehicles. By 2011, it had more than 30,000 members, according to Hain. Any sworn officer can join after filling out a membership application online for a $19.95 processing fee. State and federal officials who assist in interdiction, such as intelligence analysts, can also be members.

“It was built by cops for cops,” David Frye, Desert Snow’s chief trainer and former director of operations at Black Asphalt, told The Post. “It’s a specialized culture.”

Using a template developed by Desert Snow, police filed thousands of automated reports through the secure Web site, whether or not the drivers had been charged, documents show. Details included the location of the stop, the vehicle identification number, the names, addresses, Social Security numbers and descriptions of the drivers.

Documents and interviews obtained by The Post show that reports were funneled to the DEA, ICE, CBP and other federal agencies. In 2009, the DEA paid $6,700 to Black Asphalt for an improved user interface with the system.. In its law enforcement-only newsletter, the National Bulk Cash Smuggling Center, a part of ICE, describes Black Asphalt as one of “its valuable law enforcement partnerships.”

In another part of Black Asphalt, users posted “be on the lookout” reports, also known as BOLOs, to single out certain drivers for police attention in other jurisdictions. The private BOLO reports generally rely on police intuition rather than hard evidence or probable cause.

In April, a California Highway Patrol officer stopped a woman driving in a Kentucky car that was littered with food wrappers and energy drinks. He did not believe her statement that she was driving to a funeral and asked her why she didn’t fly. She did not have good answer, he said. So he posted her driver’s license number and urged other police to be on the lookout. “She will be loaded coming back for sure,” he wrote.

To meet the growing demand for training, Desert Snow each year has cultivated up to 75 of the most successful and aggressive interdiction police officers from around the country. A part-time job at the firm’s seminars was considered prestigious. Among the trainers are Royal Knights, the stars of the interdiction world.

Desert Snow charges as little as $590 for an individual for its three- and four-day workshop of lectures and hands-on training in such subjects as “roadside conversational skills” and “when and how to seize currency.” The firm often sets up its training in hotel conference rooms. The firm’s three-day “Advanced Commercial Vehicle, Criminal & Terrorist Identification & Apprehension Workshop” cost 88 students a total of $145,000, according to a price list posted by the state of New Jersey.

Police are taught the techniques that David had refined over the years, including how to assess the driver for signs of nervousness. “As a general rule, the innocent motoring public doesn’t lie to you,” Frye, Desert Snow’s chief trainer and a part-time deputy in Nebraska, said in an interview.

If asked in court if it is normal for drivers to be nervous after being stopped by police, they are instructed to say: “While it is true that most people are nervous when stopped by law enforcement, my training and experience has shown that once persons who are not engaged in serious criminal activities learn what type of enforcement action is being taken, their nervousness subsides.”

Frye said the firm does not teach racial profiling. “We never have and we never will!” BlackAsphalt.org proclaims on its Web site. “We teach officers to conduct legal traffic stops and how to identify major criminal activity by taking into account the totality of the circumstances on each and every traffic stop.”

Frye, who was also a former Nebraska state trooper, said Desert Snow instructors look for “indicators” of criminal activity. Indicators cited in Desert Snow training materials obtained by The Post include air fresheners hanging from rearview mirrors, trash on the floor and the driver’s demeanor, such as being too talkative or too quiet.

“Indicators are seemingly innocent things heard, smelled and/or observed during an enforcement encounter, including the contents of the vehicle, what was said, and the manner in which it was said, which when taken in their totality and compared with the innocent motoring public and traffic patterns of that geographic area, along with the officer’s training and experience, show reasonable suspicion or probable cause that criminal activity was, is, or will be taking place,” the material states.

A cornerstone of Desert Snow’s instruction rests upon two 1996 U.S. Supreme Court decisions that bolstered aggressive highway patrolling. One decision affirmed the police practice of using minor traffic infractions as pretexts to stop drivers. The other permits officers to seek consent for searches without alerting the drivers that they can refuse and leave at any time.

“Police Officers Are Not Required To Inform A Motorist At The End Of A Traffic Stop That He Or She Is ‘Free To Go’ Before Seeking Permission to Search The Motorist’s Car,” the training material says.

Desert Snow urges police to work toward what are known as a “consensual encounters” — beginning with asking drivers whether they mind chatting after a warning ticket has been issued. The consensual chat gives police more time to look for indicators and mitigates later questions in court about unreasonably long traffic stops.

They’re also instructed in how to make their stops and seizures more defensible to judges. “One Of The Most Critical Areas Scrutinized By The Courts Is The Reason For And The Length Of Any Detention,” the material says.

As business boomed, David bought a yacht and a condo in Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, and invited associates down for fishing trips, interviews and documents show. Starting in 2010, the firm began spending tens of thousands each quarter on the lobbying firm Brandon Associates to stoke interest in interdiction training in Washington — almost $200,000 in all through last year. Brandon Associates has arranged meetings with senior officials at DHS, documents show.

Success has not shielded the company from criticism. Some of it has come from current and former Black Asphalt users who felt the site tolerated unprofessional behavior in its secure chat rooms. “We have to start policing ourselves and remembering that we are professionals,” wrote DEA Agent Donald Bailey, now retired, in a chat room. “I have seen some postings and language on here that have made me cringe and can’t believe that it was ever posted.”

Computer-generated animations made by a Desert Snow marketing official featuring a cartoon cop called Larry the Interdictor have drawn especially ribald commentary. One is set in a courtroom where Larry insinuates that the defense lawyer questioning him is gay. He testifies that he disdains “Rastafarian douchebags who do nothing all day but smoke weed, live with their mom, and beat off to kiddie porn.”

The video prompted hoots from Black Asphalt users online.

“omg i’m still rolling!!!! this has got to be the funniest stuff ive ever heard!” one user wrote.

“DUUUUUUUUUUUUUDE! That crap is HILARIOUS!” said another.

“Thanks for the video laughs,” Joe David wrote. “It was great.”

Larry the Interdictor was created by Hain, the Kane County deputy and author of “In Roads.”

Hain told The Post said he made some of the videos as a hobby, on his own time. Others were part of a monthly marketing initiative at Desert Snow “to deliver information and statistics in an entertaining format,” he said. He said he did not write all the scripts but declined to detail who did.

The Black Asphalt report narratives sometimes went on for 400 words or more, and included an officer’s intent and attitude toward defendants. Some of them were meant to be humorous and earthy. This one, about a $2.5 million cash seizure, went out to 18 DEA agents:

“The driver starred [sic] blankly to the ditch, more than likely with visions of himself running through it,” one Black Asphalt report said. “But as he was fantasizing about freedom, it gave me another good look at his carotid and he was thumping. Crazy thing, but my mouth went dry. I could see that this guy was truly scared, and all I could think was ‘oh boy this is going be good.’ ”

Law enforcement authorities in several states began cautioning that Black Asphalt might run afoul of laws requiring prosecutors to disclose any relevant case information to criminal defendants. In several interviews with The Post, Black Asphalt members said they did not share the reports with their superiors or prosecutors because they did not think they had to.

In 2012, Kurt F. Schmid, executive director of the federal HIDTA task force in Chicago, wrote in a letter to the International Association of Chiefs of Police that such reports are “outside the bounds of [law enforcement] information flow” and so would not be made available to defendants.

“Courts around the country are extremely vigilant at ensuring appropriate disclosures are made to defense counsels at criminal trials,” said the letter, a copy of which was obtained by The Post.

Frye has recently said in a posting on Black Asphalt that officers can address any disclosure issues by sharing Black Asphalt reports with their prosecutors. “The whole discovery argument is BS and ultimately comes down to the officer working with their prosecutors to determine what they need for each case,” he wrote.

Iowa and Kansas prohibited police from filing reports into the system. Kevin Frampton, director of investigative operations at the Iowa Department of Public Safety, wrote on March 1, 2012, that the state attorney general determined that state police “sharing intelligence or investigative information with a private company creates an increased risk for civil and criminal liability for officers and the department.”

On June 11, 2012, Assistant U.S. Attorney Deborah Gilg in Nebraska warned in a letter to state law enforcement there that such reports “may, in fact, violate state criminal law(s) and citizens’ civil rights and liberties” because they contained law-enforcement sensitive information and personal data on citizens.

Hoping to maintain confidence in the system and provide an official imprimatur, David and Frye in 2012 asked the Logan County Sheriff’s Department in Guthrie, Okla., to take control of the Black Asphalt system.

“Since taking control of Black Asphalt Law Enforcement Network in August of 2012 the entire website has been overhauled, updated, and improved,” Logan County Sheriff Jim Bauman wrote in an open letter to police.

In an interview, Frye acknowledged that he and other Desert Snow trainers were on loan to Logan to help run the system. A search of the term Black Asphalt on Google takes computer users to the Desert Snow site.

David and Frye also have sought guidance from the Bureau of Justice Assistance at the Justice Department. David P. Lewis, a senior policy adviser at Justice, said it was “a positive step” that the network had gone under the authority of Logan County, according to a December 2012 letter obtained by The Post. Lewis said the network was then being used by 12,000 officers who accessed the system 1,000 times a day, an apparent decline from previous years.

“We recognize the unique and innovative nature of the Black Asphalt Web site and its efficacy for law enforcement,” Lewis wrote. “However, it is not a criminal intelligence system” subject to federal law.

Lewis pointed out it did not meet federal standards for police intelligence systems, which require police to evaluate the information for relevance and a “reasonably suspected” link to criminal activity. It made 11 recommendations for improving the site, including requiring that BOLOs “be limited to situations of ‘significant investigative interest’ ” and “be based on ‘credible and reliable’ information.”

In June, the Logan County Sheriff’s Office announced that it was handing over control of Black Asphalt to the sheriff’s office in Kane County. The point of contact is Deputy Ron Hain, the author of “In Roads” and the creator of Larry the Interdictor.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments