This is Part 15 in a series about Radical Municipalism looking at ways people worldwide are organizing in their cities to build power from the bottom up. Read Part 1 (Brazil), Part 2 (Rojava), Part 3 (Chiapas), Part 4 (Warsaw), Part 5 (Bologna), Part 6 (Jackson, Miss.), Part 7(Athens), Part 8 (Warsaw & New York), Part 9 (Reykjavík), Part 10 (Rosario, Argentina), Part 11 (Newham, UK), Part 12 (Valparaiso, Chile), Part 13 (Porto Alegre, Brazil), Part 14 (Montevideo, Uruguay), and Part 15 (Venezuela).

“It was an important milestone and victory for poor and working class people in the struggle for decent affordable housing,” members of a housing activist group in Cape Town, South Africa, called Reclaim the City, said following a recent municipal government announcement to build hundreds of social housing apartments in the Waterfront area of the city center.

This news this fall was testament to the pressure mounted by the housing movement that continues to make ground in a city still strongly divided by racial inequality. Founded two years ago, Reclaim the City employs a broad range of tactics that include occupying government land and leading a popular participative movement of tenants and workers. Their movement works outside the city's institutions to pressure action, demonstrating an effective pathway and model for radical municipalism.

The long walk to equality

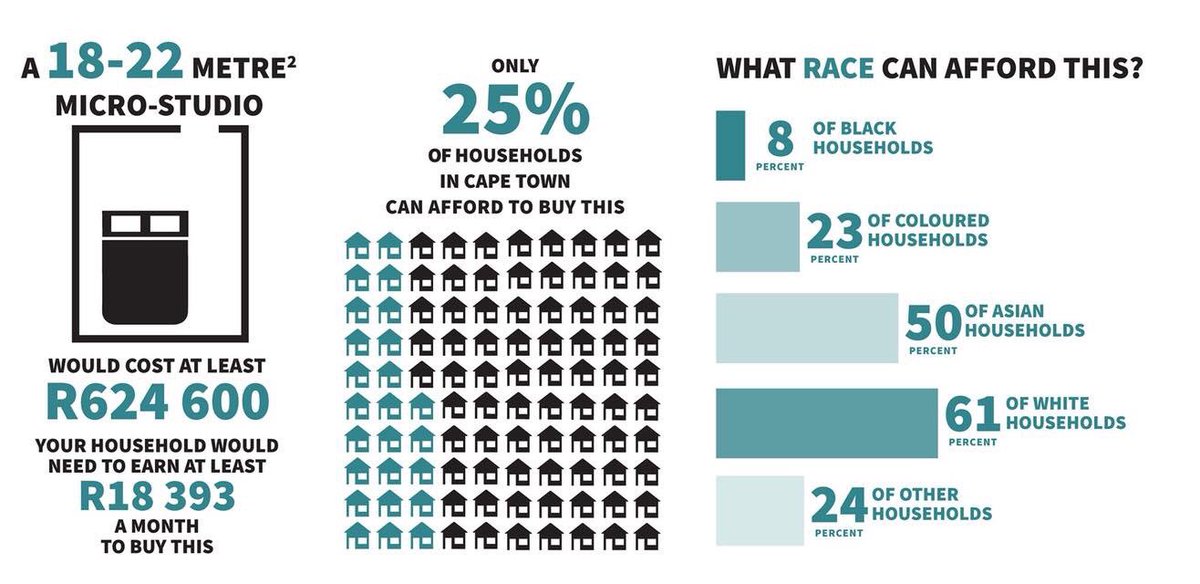

Social movements that succeed pushing cities to build social housing in central, desirable locations is an achievement anywhere. In Cape Town, it is more remarkable and desperately needed. The city is built on structural racism, which was set into law during South Africa's apartheid period of 1948 to 1994.

Now, a quarter of a century after the fall of apartheid, the city still faces a long journey toward economic equality. The legacy of apartheid remains especially visible in the realm of housing, which makes Cape Town's decision even more notable a milestone.

South Africa is hardly alone. Housing reveals racial inequality in many global cities. Groups excluded by race and class often either live in cramped conditions in city centers where they face the threat of eviction from gentrification – a process many see as a form of social cleansing. Elsewhere, the poorest live on cities' outskirts in shanty towns, favelas, slums and projects.

South Africa's excluded live in townships. Under apartheid and following the 1950 Group Areas Act, South Africans were divided by racial groups. The most prestigious homes were reserved for whites only. People of mixed descent were allocated in less desirable housing. Black people native to South Africa were forced into townships with the worst living conditions. Even today, the towns lack running water and sanitation, and homes are often of poor quality, made from corrugated iron and other waste materials.

Inequality is particularly stark in Cape Town. Billionaires moor their super-yachts in the same Waterfront area where the new social houses are to be built. It is truly a tale of two cities: the whites with money shop and relax in the Waterfront area, while the predominantly poorer black population travels for hours to reach work in the same Waterfront area. This type of inequality has only been compounded by Cape Town's recent drought.

Occupying 'public land' to make it public

Reclaim the City was born in early 2016, founded by Ndifuna Ukwazi, a clinic of lawyers who advocate on behalf of social justice issues and provide information for community activism and human rights. Conceived of as a tenant and workers movement, its first aim was to pressure the government to turn publicly held land into social housing rather than sell it off to developers.

In autumn 2016, the local government was far from interested in listening to Reclaim the City. Members of the organization visited municipality offices to discuss turning the former site of a school into social housing. But the city refused to even come down from their offices for the meeting. So Reclaim the City occupied the building's lobby.

Reclaim the City has not only held sit-ins in government offices. They have also occupied empty publicly owned properties. One example is the abandoned Helen Bowden Nurse's Home, a Waterfront property occupation that Cape Town's premier wants to end.

In March 2017, people who lacked affordable housing occupied the buildings that formerly housed nurses. The site had been deemed suitable for social housing as early as 2012, but the Western Cape government had ignored the proposal.

Along with the occupation, Reclaim the City is also pushing through official channels. For instance, it wrote to the city's deputy mayor about converting a plot of public land in the Green Point area into public housing.

Ndifuna Ukwazi, which translates as "dare to know," carries out strategic litigation including cases aimed at pushing for the right to housing, and often takes claims from residents to challenge specific housing sales or evictions. Recently the group uncovered how the local government drastically undersold a large plot of Cape Town to a developer.

The occupied former nurses' home has become a focal point in the Cape Town housing struggle. Controversies surround the occupation; one being the unanswered questions around a dubiously expensive security contract taken out by the municipality. One of the security contractors is accused of murdering a Reclaim the City activist, Zamuxolo Dolophini.

In another matter of unanswered questions, researcher Crispian Olver is publicly asking whether Western Cape officials have something to hide, after he successfully got information about housing policies in cities across South Africa – but was denied his requests by the Western Cape administration.

Progress towards reclaiming Cape Town

Taking small steps, one at a time, Reclaim the City and its allies are gradually forcing Cape Town to move away from its ongoing housing apartheid. The September victory in the Waterfront area follows an announcement last summer that Cape Town would build social housing in 10 other inner city locations.

Brett Herron, who sits on the mayoral committee responsible for managing housing and transport, called the city's decision to address housing inequality a u-turn in Western Cape policy. Meanwhile, Helen Zille, the Premier of Western Cape, responded to Reclaim the City's occupation of the former nurses' home with a comment revealing just how out of touch many in power still remain touch: "The illegal occupation of Helen Bowden Nurses Home... remains a real threat to our ability to proceed with affordable housing.”

Read: Part 1 (Brazil), Part 2 (Rojava), Part 3 (Chiapas), Part 4 (Warsaw), Part 5 (Bologna), Part 6 (Jackson, Miss.), Part 7(Athens), Part 8 (Warsaw & New York), Part 9 (Reykjavík), Part 10 (Rosario, Argentina), Part 11 (Newham, UK), Part 12 (Valparaiso, Chile), Part 13 (Porto Alegre, Brazil), Part 14 (Montevideo, Uruguay), and Part 15 (Venezuela)