Bianca Rodriguez, a Philadelphia school reading specialist, was 22 years old when the seizures started. A year later, after she developed more mysterious symptoms, including swollen joints and an outbreak of hives, Rodriguez finally received a diagnosis: adult-onset Still's disease, an autoimmune disorder that can cause high fevers, joint pain and severe fatigue.

Beset by unpredictable flare-ups, Rodriguez was forced to stop working. "Some days I might be able to carry 50 pounds, but the next day if I have an onset, I won't be able to pick up anything or even move at all," she says; at one point, she was paralyzed from the waist down for two months. To make ends meet, she spent down her savings, and applied for food stamps and other public aid programs. For two years, she was able to get $200 a month in General Assistance — Pennsylvania's state welfare program for childless adults — but lost that in 2011 when the state announced that it would soon eliminate the program entirely.

Meanwhile, Rodriguez had also applied for Supplemental Security Income (SSI), the government program for poor adults and children with disabilities, but was turned down time and again over the course of three years. "I just looked at one of the papers and cried," she says.

Like many of the nearly 50 million Americans currently living below the poverty line, Rodriguez makes ends meet by cobbling together food stamps, government utility discounts and any other money from odd jobs that she can take on, like doing hair on the days that she feels physically able. But as someone who’s not working full-time, she could soon find a new obstacle in her path.

This week, House Majority Leader Eric Cantor is expected to introduce a food stamp bill that would require that many applicants seeking food stamps (through the newly renamed Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program, or SNAP) prove that they're either working 20 hours a week or are unable to work — or else be denied aid. It's a measure that could endanger benefits for as many as four million of the 48 million Americans currently receiving food stamps.

Cantor's bill is the first step in a push by House Republicans and conservative think tanks to complete the unfinished business of Newt Gingrich's 1994 Contract With America, the 10-point plan for conservative reform that envisioned "promoting individual responsibility" by attaching expanded work requirements, time limits and other restrictions not only to welfare — which Gingrich and others succeeded in passing in 1996 — but to food stamps, SSI and other government benefit programs.

"The work requirements piece is a constant drumbeat," says Rebecca Vallas, a longtime legal advocate for the poor in Philadelphia. "It's not that different from the mid-'90s. We're really seeing a reemergence of the same strategies, of the same kind of messaging, even from the same players."

Architects of Welfare Reform

Vallas notes that the top staffer on public benefits at the House Ways and Means Committee Human Resources Subcommittee, which has oversight on public benefits programs, is Matt Weidinger, who began his career 20 years ago as an aide to Florida Rep. Clay Shaw, a welfare-reform champion who once warned that "the inscription at the base of the Statue of Liberty was written before welfare." The subcommittee has spearheaded efforts to restrict public benefits, most recently holding a hearing on poverty in late July that focused mostly on ways to move the poor into "self-sufficiency."

At the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), home to The Bell Curve author and welfare-reform godfather Charles Murray, resident scholar Richard Burkhauser has cited rising SSI rolls as an indicator of a "disability epidemic," and called for new laws to "prioritize" work over cash benefits for people with disabilities. Longstanding think tanks such as AEI have been joined by the newly formed Secretary's Innovation Group (SIG), a network of state welfare officials headed by Jason Turner, the '90s-era welfare administrator in Wisconsin and New York City who blamed poverty on "enforced idleness." He once landed in hot water after telling an interviewer, "It's work that sets you free" — apparently unmindful that he was quoting the phrase posted over the gates of Auschwitz.

SIG, in particular, has been at the forefront of the effort to attach work rules to numerous benefit programs. When two House committees held hearings on poverty on the same day in July, both invited SIG chair (and current Wisconsin welfare chief) Eloise Anderson to testify; she called for time limits on all public benefits in order to break families' "cycle of dependency." SIG's main policy statement calls for not just attaching work requirements to food stamps, but also giving states the option to add "pro-work incentives" to disability programs as well.

Work requirements sound innocuous enough — if poor people can work, why shouldn't they be asked to do so before collecting government aid? But in practice, the work rules put in place by the 1996 welfare law that converted the Roosevelt-era Aid to Families with Dependent Children into Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) have had a troubled history. With few exceptions, states haven't actually placed people in jobs; rather, most have imposed a "work activity" process that requires applicants to spend weeks updating their résumés and going door to door looking for jobs — often before they can receive any cash benefits.

It's a system, though, that has been extremely successful as a means of diverting people from getting on the rolls on the first place.

"What really happened under TANF is that it's been much more about cutting people off for one reason or another — time limits, sanctions, anything we feel like — than it has been about increasing work," says Liz Schott of the D.C-based Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Indeed, since 1996, welfare caseloads have plunged even as poverty has rebounded from its Clinton-era lows [see graphs below], with some states now limiting cash aid to only a few thousand adults.

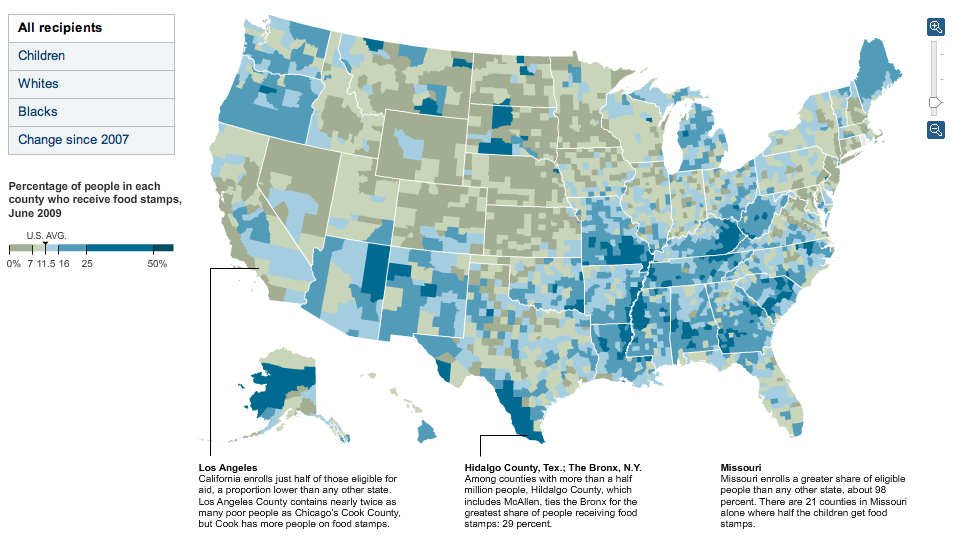

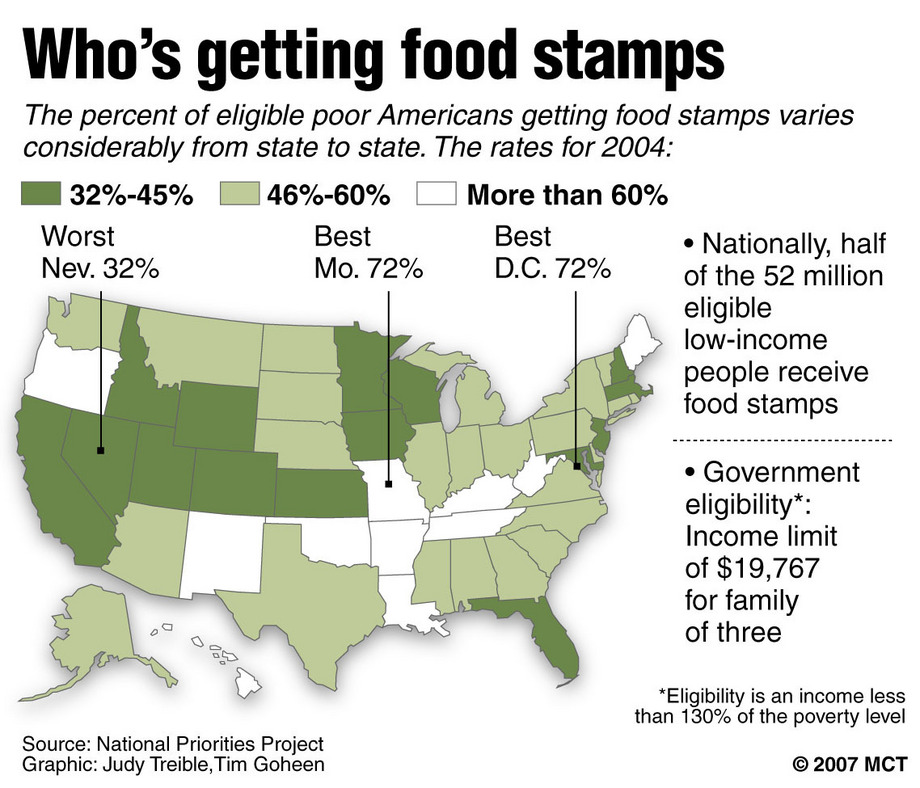

As the economy has flagged in recent years, food stamps, which were mostly unaffected by welfare reform, have soared to record highs. The 1996 law did allow states to impose 20-hour-a-week work rules and three-month time limits on food aid for so-called ABAWDs: able-bodied adults without dependents. However, states with "insufficient jobs" — which in practice has meant nearly all states — could request waivers. And since, unlike TANF, increased food stamp spending is covered by federal funds, most states have chosen to exempt their poor childless adults from work rules and time limits.

That would change under Cantor's plan, which would rescind all ABAWD waivers, forcing local governments to immediately impose work requirements and time limits on single adults. Meanwhile, Florida Rep. Steve Southerland has proposed an even more sweeping work requirement for food stamps, introducing an amendment to the farm bill in June that would have allowed states to cut off food stamps to anyone not working 20 hours a week — and keep half the resulting savings to spend on other state programs. (Southerland's amendment passed the House, with Cantor's backing, but ultimately sank the entire farm bill when Democrats opposed to the work requirements joined with Republicans opposed to any food stamp funding and voted it down.)

This, notes Schott, would create a huge incentive for states to reduce the food stamp rolls by any means necessary, especially since under Southerland's bill there would be no strings at all attached on how states could spend their savings. "It could be tax cuts for the rich," Schott says. "You don't have to pretend it has anything to do with feeding needy people."

Once Evicted, Twice Burned

Atlanta resident Lisa Jones found out firsthand the pitfalls of work requirements — even though she's mostly been employed over the course of her adult life. Her one attempt at applying for TANF, during a jobless spell four years ago, was denied when she missed her first scheduled day of job training to stay home with her sick 11-year-old daughter.

A year later, Jones was back at work as an embroidery machine operator when the temp agency abruptly stopped paying her. The company found a new temp agency to rehire her to do the same job. But when her assignment ended a few months later, she was informed by her landlord, the Atlanta Housing Authority (AHA), that her rent would be increased because she was no longer working.

This was due to a provision of yet another 1990s-era work rule called Moving To Work, which allows local housing authorities to provide "incentives" for residents of public housing to work. (Georgia has been one of the most aggressive states at imposing these rules.) The AHA had at first reduced Jones's rent because she was employed — but now the authority ruled that because she had "quit" the original job after being stiffed on paychecks, she was no longer eligible. Unable to pay her bills, she was evicted; her belongings were tossed into the street while she was at work, she says, and most of them were stolen. She and her daughter ended up sleeping on sofas for several months, once even spending a weekend in a car.

Jones, who eventually found a publicly subsidized private apartment, is once again unemployed. After surviving by visiting food pantries and "living on air," as she puts it, she was finally successful in reestablishing her food stamp case after her pay stubs had been initially denied as illegible — something she only resolved by staging a one-woman sit-in on the application line.

"Personally, I think the work requirements are ridiculous," Jones writes via email from her local public library. (She is currently without a working phone, a common difficulty for those living hand-to-mouth, and one that can make job searches especially vexing.) She is planning to go back to school to complete her college degree, while looking for a new job. "Most of the people I know are working or want to work. I could never figure out, how does one find a job when a large percent of the country is underemployed or unemployed?"

Denying benefits for those unwilling — or unable — to work is part of a long tradition of dividing low-income families into the "deserving" and "undeserving" poor. The early years of the Roosevelt-era law, AFDC, notes Columbia University poverty historian Stephen Pimpare, included "suitable home" requirements that allowed the government to deny benefits to women it decided were engaged in immoral behavior (such as allowing a man into the house).

Such appeals to the relative worthiness of the poor have "always been deeply racially coded," according to Pimpare — and help to exploit race and class divides among the less than well-off. "Are you unhappy with your life? We can explain why! It's these people who go around doing nothing — and being all black and stuff, because that's always the subtext." Looming showdown over cuts

With food stamps having been stripped from the farm bill and facing expiration at the end of the month, the House could vote on a standalone food stamp bill as early as next week. In addition to the elimination of work-rule waivers, Cantor is expected to propose slicing another 1.8 million SNAP recipients whose incomes are above the poverty line, but whose disposable incomes are below it, thanks to high housing or child care costs. (The amount of food stamps available per person — currently averaging $133 per month — is also set to be reduced by about 10 percent once increases put in place by President Obama's stimulus plan expire in November.)

House Republicans have said they'll be seeking a total of $40 billion in food stamp cuts over the next decade; if these pass, they will need to be reconciled with the bill that the Senate passed in May, which lacks the House version's cuts — but which does include one new "undeserving poor" provision, introduced by Sen. David Vitter, that would bar for life anyone who had ever committed certain classes of violent crime.

For Rodriguez, her disability would seem to exempt her from Cantor's limits on able-bodied recipients — except that as she's found, proving you’re not able-bodied can be a difficult hurdle. To her, the suggestion that public benefits are too easy to get is bizarre. "Easy to get?" she says, laughing. "That's not true for me. I don't know if it's just because I have a rare disease and they don't know much about [it]— but I don't think that should matter, because I have a medical history, and I have documents."

If public benefits programs are to be reformed, she says, it should be to require that public officials stop approaching every applicant as a potential fraudster. "If we had a chance to work, we would work," she says. "Who doesn't want to get money and become successful?"

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments