If the long and painful trends are likely to continue, if they are deeply rooted in the way the underlying corporate-dominated system is designed, and if the old ways of hoping the trends might be altered are pretty much illusions—what then?

Yes, lots of folks are doing very creative things; lots of wonderful organizing, great local projects, and important experiments with self-organizing and open-source theory are under way. Some are testing out civil disobedience. Exciting green projects, in particular, are exploding around the country. All part and parcel of getting serious about real movement building. All important, all part of where we need to go.But if the box we are in is truly systemic, will this, in fact, get us where we need to go? What do we really need to do to change the largest, most powerful system in the world? How, really, do we proceed?

Moreover, except briefly, we haven’t even begun to discuss the ecological crisis, to say nothing of climate change, and the nation’s—indeed the world’s—addiction to economic “growth.”

Now the hard work begins.

Margaret Thatcher, the famous conservative British prime minister, coined the term TINA to popularize her belief that “There Is No Alternative” to one or another variety of corporate capitalism (especially one with a very thin veneer of public programs).

Truth be told, most Americans in their heart of hearts almost certainly think she was right and cannot really imagine any genuine alternative. (Or they have simply given up on “systems.” There are some pretty serious anarchists out there these days.)

But of course, if we face a systemic crisis—if the system is the problem (and if the old balancing mechanisms are rapidly disappearing)—then either an alternative to corporate capitalism (to say nothing of state socialism, or whatever name we give the other old system) must be found, or we are obviously in deep trouble.

Accordingly, and simply to begin to dig just a bit more seriously into the problem, here’s a brief review of some of the major historical systems and how they have been structured.

For the most part political-economic systems are largely defined by the way property is owned and controlled (particularly productive economic property). It tends to produce political as well as economic power.

Thus, all too briefly:

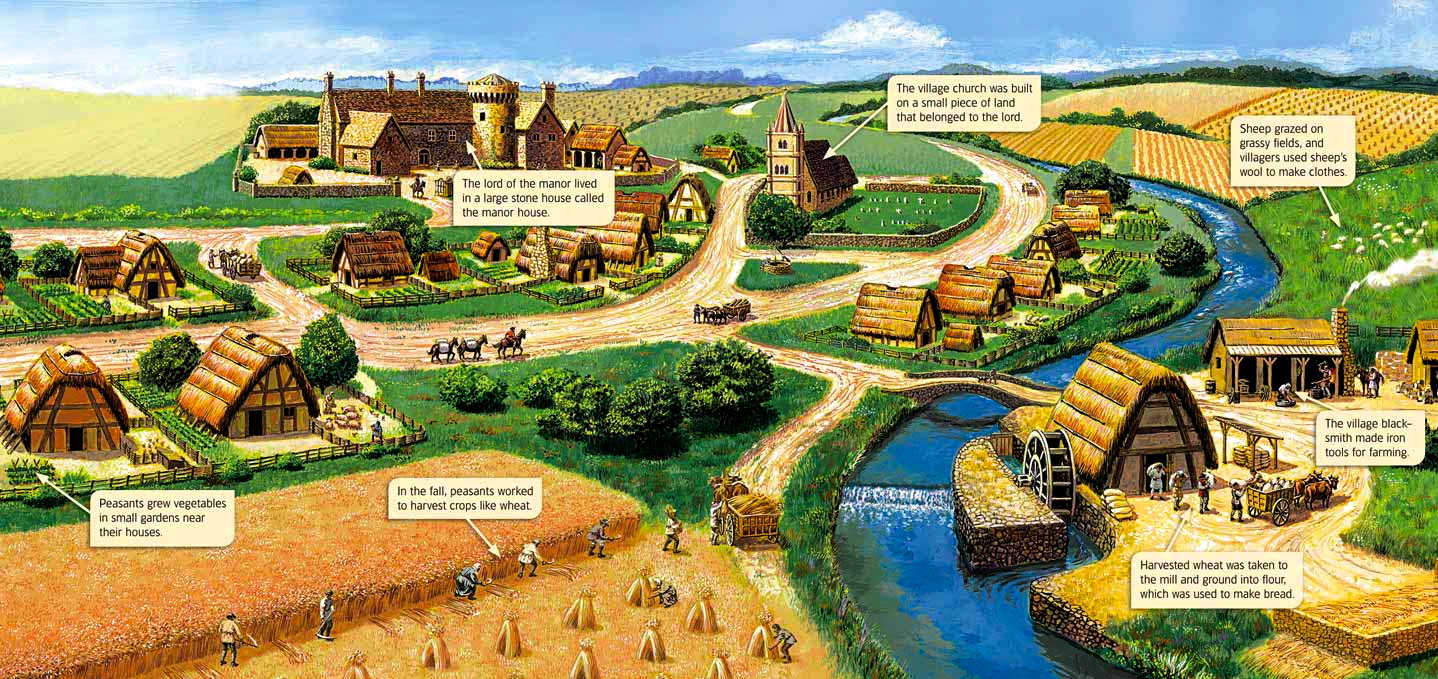

• Feudalism was a political-economic system structured above all around who controlled productive land—namely the lords, church, and king, not the peasants.

• Nineteenth-century free-enterprise capitalism was largely structured around small- and medium-scale competitive entrepreneurial capitalist ownership.

• State socialism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe was structured around state ownership of productive wealth.

• Corporate capitalism has so far come in three broad flavors:

-

Fairly pure corporate domination of the kind that emerged in the late nineteenth century in this country—and to which the trends may now be pointing again unless a different path forward is developed (the end point of which could be a corporate state).

-

“Managed corporate capitalism” balanced by labor of the kind common in many European nations (with union strength, as in Sweden, sometimes more than double our own) and, to a much lesser degree, the system mainly operating in the United States circa 1945–80.

-

Fascism—corporate capitalism managed by authoritarian rule of the kind that existed in Germany, Italy, and Spain during the 1930s and 1940s and (in different form) among some Latin American dictatorships until recently.

• Socialism with Chinese characteristics has so far been an odd mix of corporate ownership plus state ownership, with authoritarian rule.

Once again, a reminder and a basic point to keep in mind about the above: The most recent estimate is that a mere 400 individuals in the United States now own more wealth than the bottom 180 million Americans taken together—a degree of wealth concentration that is accurately, not rhetorically, properly designated medieval.1

Since political power in large part seems to go along, one way or another, with economic power, this particular number (along with the corporations that such wealth concentration also controls) is obviously something to keep your eye on.

The first system question to struggle with—if you don’t happen to like any of the above—is whether there might be an alternative, even in theory.

The second question is whether there might be a path from here to there even if we knew where “there” was.

Both questions, in turn, lead to two additional questions.

Are there any ways to begin to conceive of a different system that might truly democratize the ownership of wealth in some way that points in the direction of a democratic system in general? (Especially since in different systems political power seems inevitably related, directly or indirectly, to a greater or lesser degree, to wealth?)

And are there any processes at work that might begin to move us in a new direction, even over long periods of time? Those are the (first) big questions, and we're going to take them in steps.

Never before have so many Americans been more frustrated with our economic system, more fearful that it is failing, or more open to fresh ideas about a new one. The seeds of a new economy—and, if we act upon it, a new system—are forming.

What is that next system? It’s not corporate capitalism, not state socialism, but something else—something entirely American.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments