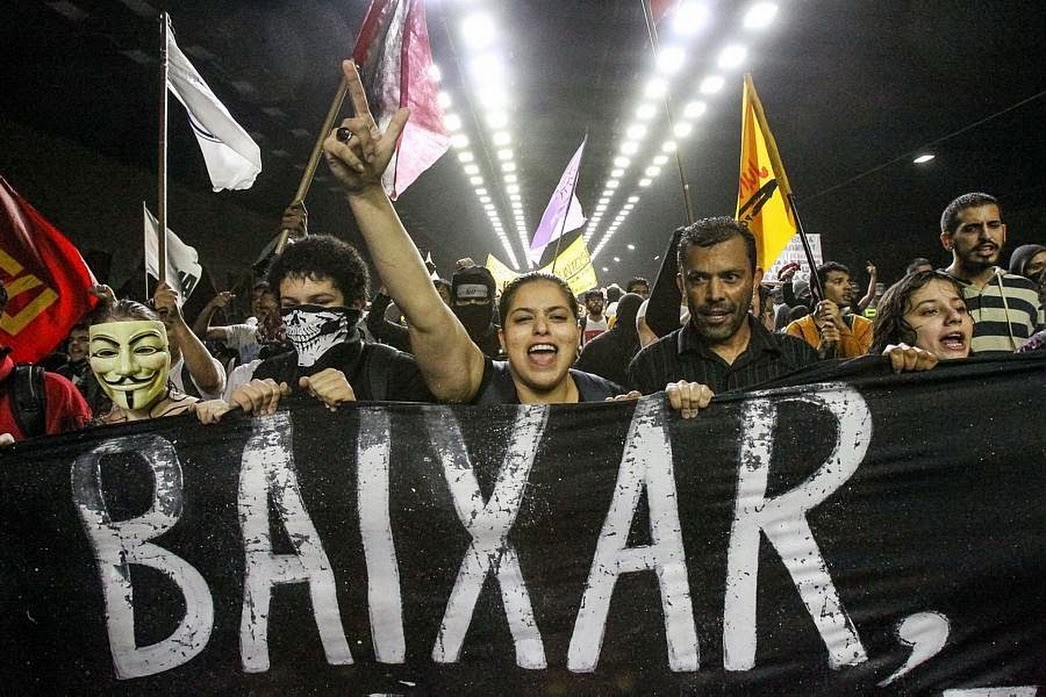

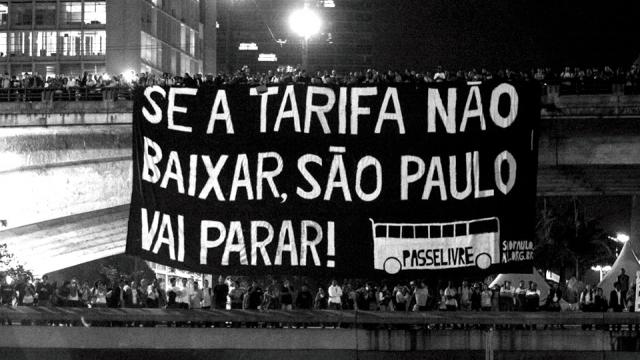

From the Internet to the streets. Indignation and occupation. Police violence and calls to action without the typical go-betweens. Choral assemblies and revolts difficult to classify. A wish for participatory democracy and empowerment. Brazil’s so-called “June Journeys” —a 2013 period that witnessed a protest breakout— placed the South American giant on the global revolt map. They shared the call-to-action format, protest architecture and other imaginaries of Occupy Wall Street, 15M, #YoSoy132 and DirenGezi.

However, Brazil’s protests embodying the #VemPraRua cry had their own personality, as well as their clear singularities. The first difference strives in that the revolts initiated by the Movimento Passe Livre did not crystallize into a new network movement with its own name.

The second difference relates to the (short-lived) invasion of media and conservative groups trying to co-opt the protests, especially in São Paulo. Ineffective use of social media, among other things, prevented the quick connection between the new protagonists on the net and on the streets. However, new imaginaries were born. From Passe Livre as a metaphor to the common cry of the media referring to the protesters with insults such as “vândalo” (vandal), “baderneiro” (troublemaker) or going through “vida sem catracas” (life without turnstiles). The connection, albeit slow and transversal, is happening in a surprising and totally unpredictable way.

Seven months after the June Journeys, protests are starting to resurface. Conservative collectives which unsuccessfully tried to co-opt the revolts back in June now seem irrelevant - at least on the streets. Online they have established influential platforms. Researcher Fabio Malini has identified five large groups under the confusing #VemPraRua umbrella.

Two were already known: those who advocate for more state intervention (leftists) and those who want less State intervention and lower taxes (neoliberals). But three new groups have emerged. The outraged (debating social action methods), the nihilists (politically disdainful) and the celebrities (largely influential in the mobilization). The five groups don’t really talk amongst themselves. They’re all, in Malini’s words, “beta movements that update as mobile apps”. And they’re ready for action in the year that will witness the World Cup and general elections.

The new network system that emerged in June has profoundly disrupted Brazilian society and politics. Popular movements of little digital presence have been joining this “indignant” left-wing network system, as well as classic militant groups. We’re seeing historical struggles at the service of a new imaginary. Who’s who in Brazil’s protest ecosystem? That inventory is incomplete. It prioritizes those collectives and networks that share methods, formats, ethics and imaginaries with the so-called “global networks”. But it also highlights Brazilian uniqueness and more classic movements.

Campsites, occupations, assemblies: The 15M and the Occupy Wall Street expansions in 2011 heavily influenced Brazil.

The network created between the different occupiers then protesting in Brazil’s cities created a mailing list called OcupaBrasil. Some of the accounts were relevant in June’s protests, such as Occupy Brazil. OcupaSampa has remained an active and relevant network in São Paulo, mostly through Twitter. What’s interesting is that some of Occupy Brasil and Democracia Real Já Brasil’s participants have played key roles in the new network created. Brasil Acorda, a network born on October 15, 2011, a day of action, is still influential.

The absence of centralized campsites in Brazil showed a clear organizational difference when compared to Spain’s 15M, Occupy Wall Street or Turkey’s Diren Gezi. However, the assembly format in public spaces has been a constant. To this day, there are still active and influential assemblies, such as the Assembleia Popular e Horizontal de BH (Belo Horizonte), the Assembleia do Largo (Rio de Janeiro) and the Assembleia Popular de Maranhão. Ocupa Alemão, centered in the Complexo do Alemão de Río favelas, is also important.

An interesting novelty on Brazil’s protests was the occupations or campsites set in front of government palaces and governors’ residences. Ocupa Cabral (in front of Rio de Janeiro Governor Sergio Cabral’s house) and Ocupa Alckmin (in front of São Paulo’s Palacio dos Bandeirantes) have been transformed into “supra-partisan” political movements. The occupations of the municipal sessions (“câmaras”) are also influential networks, such as Ocupa Câmara Río and the long list of others occupations found on Facebook. In some cases, the occupations and assemblies resulted in commons platforms such as Belém Livre (in the north of the country).

Mobility, transportation: Brazil’s revolts were born indisputably in an urban matrix. The Movimento Passe Livre called for initial protests against the bus fare hike. Their slogan, “Por uma vida sem catracas” (for a life without turnstiles), went beyond its semantic realm and is probably the most popular one from Brazil’s protests. The Passe Livre is still alive and is now tackling a new fight in Rio de Janeiro. The action/movement ecosystem surrounding zero fare, free pass or “pula catraca” (jump the turnstile) is enormous. The website tarifazero.org has an inventory of all related collectives, which highlights Tarifa Zero en Belo Horizonte, Bloco de Lutas pelo Transporte de Porto Alegre and Eu Pulo Catraca.

One of the most interesting mutations of global revolts is the proliferation of “catracaços” (collective turnstile jumpers) after the Brazilian protests. The Brazilian Passe Livre’s visit to Mexico transformed the latter country’s #MetroPopular campaign into the #PosMeSalto movement. The catracaços hold direct conversations with movements such as Occupy Wall Street’s “We Don’t Pay,” Greece and Spain’s “Yo No Pago,” Spain’s “MeMetro” and “Stop Pujades,” Sweden’s “Planka” and Turkey’s “#AkbilBasmaTurnikedenAtla”.

Common Urban Goods

The urban occupations and movements surrounding the common goods are important aspects of global revolts. In the case of Brazil and Turkey, the urban issue becomes both cause and platform, objective and political interface. Occupy and 15M’s campsites hold organic dialogues with occupations in Brazil. So do Turkey’s movements and networks. For example, the Movimento Fica Ficus de Belo Horizonte held conversations with the Gezi Park protesters on June 9, before talking to São Paulo. The Turkish #direnODTU (collective tree-planting) initiative mirrors the Movimento Pró-Árvore (Fortaleza) and the Planta na Rua RJ (Rio de Janeiro). The Salve o Cocó movement (Fortaleza) and the Direitos Urbanos group (Recife) have been as important in Brazil’s protests as the IMECE orMülksüzleştirme Ağları (Networks of Dispossessions) were in Turkey. For its part, the Parque Augusta movement, the latest mutation of São Paulo’s protests, is already holding talks with urban space collectives such as Campo de Cebada in Madrid.

A special Brazilian trait is the growing importance of the World Cup’s Popular Committees. The committees emerged against FIFA’s neoliberal steamroller and wasteful spending of public funds, and focus especially on the fight against evictions and displacements. Except for the geographical location, these committees’ anti-eviction role is as vital as the Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca(PAH) within the 15M ecosystem. In this field it’s worth mentioning the Defesa Pública da Alegria network movement, born from an anti-FIFA action at the end on 2012, as well as more traditional movements such as Frente de Luta por Moradia, the Organização Anarquista Terra e Liberdade OATL and the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Teto.

Mass Self-communication

The heavy media concentration in Brazil and the media manipulation have been causing outrage for years. Profiles criticizing media, such as Ocupa a Rede Globo, Globo Mente and the very powerful Rede Esgoto de Televisão (more than one million “Likes” on Facebook) are vital in counter-communication and mobilization. Actually, the “occupy the media” imaginary (present in the 15M’s “TomaLaTele,” Occupy’s “Occupy News,” Turkey’s “OccupyGeziNews” and Mexico’s “Ocupa Televisa”) sparked the birth of #OcupeAMídia.

Despite the opportunistic moves by big media and other organizations, the independent media ecosystem has not stopped growing. The mass self-communication that Manuel Castells talks about, which goes beyond the independent media concept, is present in phenomena such as Mídia Coletiva Independente (MIC), Fotógrafos Ativistas (very similar to FotoMovimento del 15M), FotoProtestoSP, Web Realidade (a list of streaming channels), Mídia Negra, Olhar Independente, Mídia Informal, MídiaLivre.org and Moqueca Mídia. Collectives created along the “rua” (street) imaginary are of special importance, such as the pioneering BHnasRuas (Belo Horizonte) and RioNaRua (Rio de Janeiro).

BRnasRuas.com holds a comprehensive RSS feed of news posted by Facebook groups and Twitter members in all of Brazil, adjusting better to the definition of “communication-connection”. Projects such as Rebaixada.org and Agrega.la, both from Rio de Janeiro, also go in that direction of extracting data from proprietary networks.

A Network of Lawyers

Police violence during Brazil’s protests helped spark the Avogados Ativistas network to assist protesters who were detained or charged with a crime. It’s an open, countrywide decentralized network at the service of the common good. The action protocol is very similar to the 15M’s Legal Sol and Toma Parte, OWS’s Occupy Legal and Occupy Law Street, Mexico’s Liga de Abogados, or Turkey’s Hakinhukuk collective. The Grupo de Apoio ao Protesto Popular would also fit into this category.

Cultural paradox: The cultural sectors, digital culture and open-source software in Brazil were practically irrelevant during the June Journeys. Despite their importance during Lula’s presidential terms, these sectors were off-balance on the networks and on the streets. Their incorporation was a slow one. However, political art and artistic interventions were and are vital. After the #YoSoy132 explosion, the Artistas Aliados platform emerged. Occupy Musicians was one of Occupy’s cultural legacies. BookCamping.cc and Fundación Robo bring lyrics and music to life for the 15M. In Brazil, the Coletivo Projetação creatively shakes off the streets by projecting slogans, imagery and imaginaries wherever they go. The Coletivo Mariachi playfully occupies spaces with audiovisual presentations. And Paulinho Fluxus, Mídia GAYsha and its Tanque Rosa Choque launch symbolic projectiles with laser tags or street-name hacking. The satirical Rafucko channel tears apart the reality-fiction of power. Audiovisual and politic-poetic remixes are the work of the Coletivo Vinhetando.

Brazil’s version of data visualization platforms such as 15Mdatanalysis and Occupy Data are organizations such as Interagentes or departments such as LABIC by the Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo. Some collectives such as Transparencia Hacker and the Casa de Cultura Digital Porto Alegre celebrated hackathons to promote transparency on public transportation accounts. The latest campaign, Marco Civil Já, is steeped in defending net neutrality.

Politics and Transparency

The occupations of sessions and power hubs speak directly to groups such as Democracia Real Ya and platforms such as #YoSoy132. But in Brazil there are many initiatives surrounding transparency and political participation. One paradox is that some collectives fighting against corruption are right-wing related, namely the national Partido de los Trabajadores (PT). This is the case of the Movimento Contra a Corrupção (critical of all parties) and A Verdade Nua e Crua (extreme right), both very influential during the June Journeys. There are hundreds, maybe thousands, of anti-corruption social media profiles. Most of them, though, break through the left/right-wing axis.

Some curious cases include Pedra No Sapato (“a supra-partisan, popular and organic group”), Eu Me Represento (“analysis, reflections and denouncements on national political action”) and Movimento Fora Lacerda (against Belo Horizonte’s mayor). The “Democracia (real) e política distribuída já!” platform or initiative is an interesting one because it defines itself as a “political transformation tool”. Transversalities

The June Journeys and their mutations have created an ecosystem of profiles, collectives and networks that are hard to classify, creating a sui generis Brazil, an anthropophagous Brazil Some profiles launched before June, such as Acorda Meu Povo (an outrage/transparency hybrid) and Geração Invencível (an optimistic mutation of Juventud Sin Futuro) are extremely influential. Other, more recent and extremely transversal examples, such as Porque eu Quis (a satire based on a phrase a police officer said) and Não Me Calarei, serve as massive mobilizers. The Beijato in Rio de Janeiro, a “transfeminist and anti-capitalist group,” has established dialogues with 15M’s Asamblea Transmaricabollo (@queer_sol on Twitter) and with the Zorras Mutantes. And even more dramatic: the humorous Isso é Brasil Facebook profile (more than one million “Likes”) or the very powerful @LeiSecaRJ Twitter account (which warns on issues related to Rio’s alcohol epidemic) have taken the protesters’ side.

Countless of groups that have stemmed from Anonymous (originally accused of being right-wing), as well as the black blocks, deserve a special mention. Based on the number of followers, it’s worth mentioning BlackBlockRJ and the Black Block Brasil group. Another special mention goes to the Black Prof action platform, born out of the alliance between Rio de Janeiro’s professors and black blocks for mutual support against the police. And there’s a carioca version of Marea Verde’s defense of education in Spain. The Anonymous ecosystem highlights Anonymous Brasil (based on the numbers of followers) and Anonymous Rio for their unclassifiable anarcho-tropicalist hooliganism.

Translated from the Spanish by Marine Perez

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments