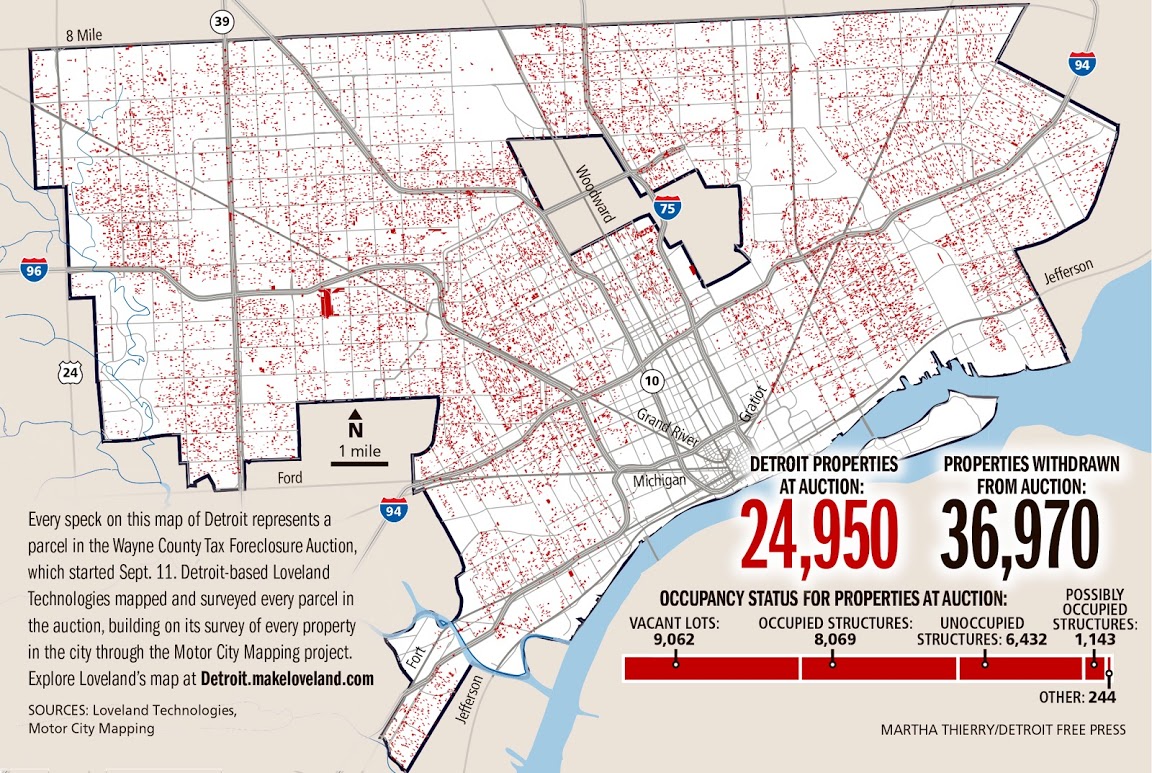

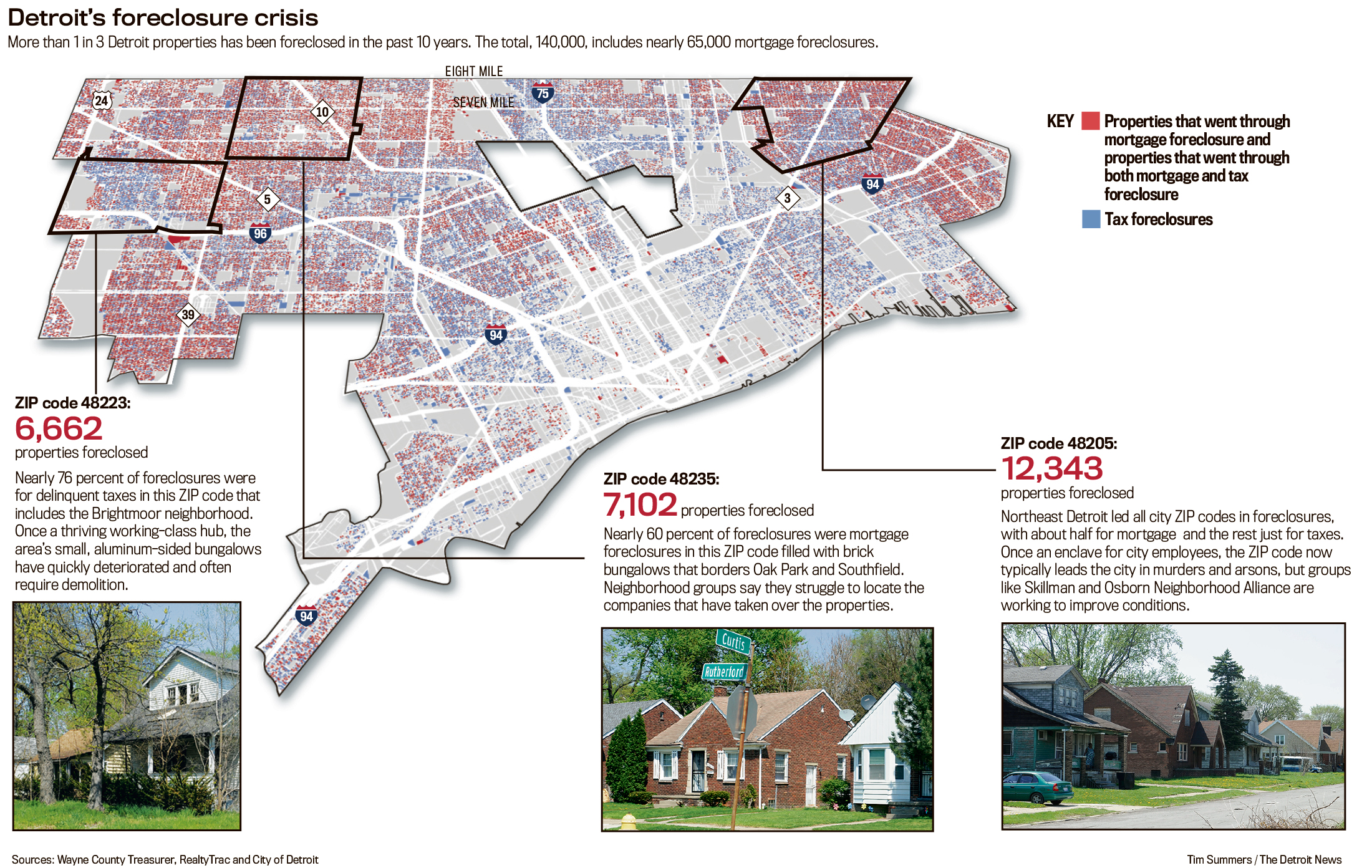

It’s Ebay on a city scale this fall in Detroit, with 25,000 properties up for sale starting Tuesday, Oct. 5 in the Wayne County Tax Foreclosure Auction. The largest known municipal foreclosure sale to date, the Detroit home sell-off could be a modern take on Manifest Destiny – luring would-be frontiersmen and speculators from across the world to try their hand at “buying Detroit.”

But the fantasy of blank-slate real-estate is no truer now than it was in the days of forging West, because nearly a third of the properties being sold are occupied homes. Native Detroiters have little more to do with this auction than Native Americans had in the sanctioned theft of their land. Often, in fact, residents here are not even aware of the fact that their home is for sale.

The auction is unquestionably an opportunity for investors to land cheap property. But as far as public auctions go, it is a farce – particularly the creative red tape that makes it increasingly difficult to take advantage of for those who need it most.

A Problem of Access

The most fundamental way in which the general public of Detroit is prevented from participating in the auction has to do with access: the auction takes place entirely online. It’s all but impossible to sell off 25,000 properties in analog form; just reading the list of addresses could take days. The Internet has enabled the auction to take its current bloated form, yet 40% of Detroit households have no broadband Internet access, and there is a dearth of public libraries. The result: basic homeowner information is often an abstraction for the very residents of those houses. Upon being notified that his property was being sold in an online auction, one troubled resident said: “On the internet? I think my neighbor has one of those.”

The lack of online access goes even deeper than participation in the auction; many residents are actually unaware that their property is in foreclosure in the first place. Most Detroit homes are rental properties, and landlords have a vested interest in keeping their tenants unaware of the pending foreclosure in order to continue collecting rent. A person who has no knowledge that their home is for sale doesn’t even have a seat at the auction table.

In some cases, tax bills and foreclosure notices are sent out to former property owners, including banks and speculators who have long since lost interest in the property – proving that information about the auction isn't easy to come by even for those with Internet access. New laws, changing rules and the general unpredictability of the auction has built uncertainty at every step of the way.

Financial Hurdles

While the bid price of a house may be as low as $500, the cost to participate in the auction is far higher: a deposit of $2,500 is required just to place a bid (up from $500 two years ago). The measure makes sense in that properties often sell for much more than $500. But because the auction requires payment-in-full within 24 hours of the closing bid, the deposit has become an obstacle for many. For example, a person who could afford to buy their property for no more than $2,000 would be excluded from bidding. The more money that's required to be paid up front, the harder it is for the average Detroiter to participate.

Another financial hurdle is a new rule, instated this year, which requires auction winners to pay the 2015 Summer Taxes owed on the property at the time of purchasing. This means that the cost of a house in auction is the sum of the bid price and the current year’s taxes, making the renowned $500 house a thing of the past.

Granted, the prior system, in which auction winners owed property taxes but didn’t know it, was a bad one. According to the rules of “reversion,” properties bought in the tax auction that then accumulated delinquent taxes could revert back to government ownership. This year alone, 18,000 properties were subject to reversion; 9,000 of those had been purchased only one year prior. But requiring buyers to pay this amount immediately, and in full, is an over-correction that further disenfranchises Detroiters from participating in the auction.

Who Gets to Own?

The last notable factor limiting participation in the auction is the new Michigan state law that prohibits former owners of the foreclosed properties from bidding. The stated intent of the law was to prevent slumlords from gaming the system; indeed, something's not right when a savvy landlord can collect rent but fail to pay taxes, only to buy the property back at auction. However, the auction has been a last option for many owner-occupants who were burdened by excess taxes and sky-high interest rates, something reaching 18%.

Upon hearing that $1,000 is too much for a Detroit resident to pay to purchase a home, people might retort: “Well, home ownership is not for everyone.” And they are right, to an extent. Home ownership, when it comes with decades-long mortgages, unreliable financing and unrealistic expectations of resale value, is certainly not for everyone. In addition to the tangible costs, ownership can reduce mobility and responsiveness to changing economies and circumstances.

However, when home ownership actually costs less than renting – when home ownership means stability for a family and a community, when home ownership means that a property doesn’t become scrapped and blighted, when home ownership is the difference between being housed and being homeless – it is absolutely the right choice for both the individuals and the community at large. That is why it's so painful to watch the opportunity that the auction represents pass so many Detroiters by.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments