On the evening of January 15, the Roosevelt Neighborhood Center in downtown Charleston, West Virginia, was packed with attendees overflowing into the hallways. People from the state capital voiced numerous concerns about using their water, even though West Virginia American Water had deemed it safe to use. One participant demonstrated to the audience how she was showering – she had bought a Coleman camp shower, essentially a plastic bag filled with boiled water that she could hang from a wall, twisting a valve on the bag to let water come out in a steady stream.

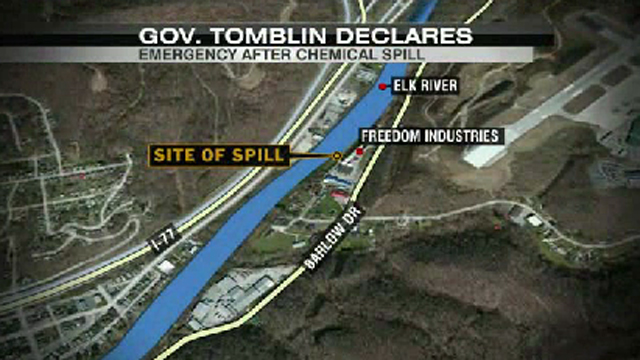

My hosts in Charleston had been bathing out of town, not using their own shower for five days. Even though bans on using water in the affected West Virginia counties have been lifted, making it technically safe to drink and bathe in, the 300,000 affected residents aren’t taking their local government or the water company at their word. Since January 9, when a chemical storage facility run by Freedom Industries spilled 10,000 gallons of the toxic coal-processing chemical MCHM (4-methylcyclohexane methanol) along with another chemical, PPH, and the cancer-causing agent formaldehyde into the Elk River, municipal water supplies for approximately 6 percent of the state have been tainted.

The spill – which wasn’t discovered until people in the Charleston area had gone to the hospital reporting nausea, eye irritation and vomiting – is the latest example of corporate malfeasance allowed to run wild. The privately-owned West Virginia American Water Company was woefully unprepared to contain the spill. And the privately-owned Freedom Industries, which spilled the chemicals, mysteriously went into bankruptcy shortly after the accident. Even after the ban on water use was lifted, government officials advised pregnant women not to drink the water, raising further suspicions of the untruths that have been told to the public.

Factor in a state regulatory body that for years has been heavily compromised by the coal industry, and the picture that emerges is a perfect storm of disaster for West Virginians. Now, the spill is leading some state natives to question the fate of the coal industry that has long sustained them economically – and causing organizers to take the state’s subpar regulation of extractive industry into their own hands.

No Data Available

There is still very little known about the MCHM chemical agent that affected drinking water for over a quarter of a million West Virginians. The Washington Post reported that the 15-page material safety data sheet on the Tennessee-manufactured chemical contains the phrase “no data available” 152 times.

Even more alarming, the Centers for Disease Control only tested one ingredient of crude MCHM, having no readily available data for the other ingredients in the chemical compound.

“I’ve been on the ground in every major water-related disaster since the BP oil spill, and I’ve never seen anything like this before,” said Scott Smith, the chief scientist for Water Defense.

According to Smith, Water Defense is using the same testing labs for their water samples used by the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection and Freedom Industries. While their results are still forthcoming, Smith said West Virginia’s government has performed similar tests but has refused to share results with the public. Water Defense executive director John Pratt says the results of Water Defense’s lab tests on West Virginia water will soon be available on Water Defense's website.

Accountability Deflected

This is the second time in four months West Virginians have had their water supplies tainted by the coal industry. In the small community of Van, an hour South of Charleston in rural Boone County, the local water supply comes from the Little Coal River, one of the Elk River’s tributaries. The Pond Fork of the Little Coal River turned white in fall of 2013 after Patriot Coal spilled 2,400 gallons of BT50D – a dust suppressant used on train cars transporting coal.

Van, a hamlet of 211 people as of three years ago, is a very coal-conscious town. The main road where most of the town’s residents live is adorned with lawn signs akin to campaign lawn signs – except instead of advertising a candidate they simply say, “friends of coal.” While West Virginians are all too familiar with the deadly consequences of coal, regulation of the industry continues to be a political lightning rod for the state’s elected officials.

Days after Freedom Industries’ spill in the Elk River, West Virginia Governor Earl Ray Tomblin, a democrat, jumped to the coal industry’s defense, saying, “This was not a coal company. This was a chemical supplier where the leak occurred. As far as I know, there are no coal mines within miles of this particular incident.”

Rather than giving his constituents a definitive answer on whether or not they can safely use their water, Tomblin has since said it’s up to the individual discretion of residents to decide whether or not their drinking water is safe.

Tomblin and Joe Manchin, West Virginia’s junior U.S. Senator, have been eager to treat coal mining operations, and the chemical storage facilities that assist in the coal burning and cleaning process, as separate entities rather than two heads of the same beast. Both Tomblin and Manchin are supporting new state legislation that would impose new regulations on chemical storage facilities like the one owned by Freedom Industries, which had not been inspected since 1991.

But their slick, band-aid approach to a more systemic problem is unlikely to pass muster, especially since both politicians depend on the coal industry for continued financial support in future elections.

Tomblin won the 2012 gubernatorial election with tens of thousands of dollars from the coal industry. Bennett K. Hatfield, CEO and chairman of Patriot Coal, which spilled BT50D in the Pond Fork river in late 2013, twice donated the maximum $1,000 contribution to Tomblin’s campaign.

Tomblin also received two separate $1,000 donations from Kevin S. Crutchfield, CEO of Alpha Natural Resources. Alpha in 2011 boughtthe notorious Massey Energy, which was known for the Upper Big Branch mine blast that killed 29 West Virginia coal miners in 2010. Alpha’s president, Kurt Kost, also donated $1,000 to Tomblin’s campaign. Tomblin additionally received $500 from James Clifford Forrest III, the owner of Freedom Industries.

According to Opensecrets.org, Manchin’s list of top campaign donors features a laundry list of coal companies and energy lobbyists. Patriot Coal put $48,400 in Manchin’s war chest, making the corporation his #9 donor. Alpha Natural Resources was his 11th most generous benefactor, donating $43,298 to Manchin’s campaign committee in the last cycle.

Both Manchin and Tomblin are dutiful defenders of the coal industry on a national scale as well. As governor, Manchin took Obama’s EPA to court in November of 2010 over the revocation of a mountaintop removal mining permit. Tomblin, after taking Manchin’s place, continued the lawsuit and organized a “Rally for Coal” in 2011. Tomblin and Manchin both made a career out of labeling the EPA as an intrusive government force – though the actual history of government inspections and enforcement of regulations has been barely noticeable in the state for decades.

Coal’s Future in West Virginia

Early in the morning on January 16, West Virginia American Water announced on its website that Van’s water ban had been lifted. Residents were told to flush out their water systems for 15 minutes with hot water, and 5 minutes for cold water. I walked the streets that day with gallon jugs of water I had bought in Maryland, looking for residents flushing out their water, knocking on doors to trade water for interviews.

Richard Bishop was flushing out his hot water when he let me into his home, where a strong aroma of licorice lingered from the faucet. Bishop used to mine in West Virginia’s mountains, but lost his job along with thousands of other miners over the years as peak mineable coal approached in 2011. Now working as a truck driver, Bishop doesn’t fault the coal industry for the chemical spill poisoning his water supply.

Instead, he blames what he feels are the burdensome government regulations that require chemicals like 4-MCHM to be used to clean coal before transport.

“My papaw was in the mines, my dad was in the mines. Back then, you didn’t have chemicals spilled in the river,” Bishop said. “You may breathe in a little coal dust if you worked near the mines, but that didn’t kill nobody, at least not until the ‘80s and ‘90s.”

On January 18, Bishop sent me several pictures of murky water in his sink that came from his faucet, writing, "The dishes I sat in the water, I had already pre-cleaned by wiping. I didn’t add anything to the water, I went to bed. When I seen the sink this morning, it had this weird glittery film on it, oil like, and something was separated from the water at about 1/4” deep."

"I have left water sitting in my sink a thousand times even with soap and bleach in it, and I haven’t ever seen anything like this in it," Bishop continued. "I even ran water into it, and it still didn’t break up the film. They told us the water is safe, we have more than flushed lines, and it is still like this."

69-year-old Nedra Abbott, a 33-year resident of Van, has a son who used to work in the coal mines until he was laid off in the mid-2000s. After he took a job at a nearby correctional facility, his former employer offered him a temporary job, which he turned down. I asked Abbott if she thought the coal industry had a future in West Virginia.

“Don’t seem to right now, does it?” Abbott said. “I think this has opened everybody’s eyes that wasn’t…You can’t live without water.”

Abbott also ruminated on the prospect of the potential loss of life in the event that a similar spill happens in the future and nobody is told about the danger to their water supply.

“It could happen anywhere there’s a chemical plant. Think about how easy it is to put poison in the water," she said. "You could just wipe out a lot of people, you know? You think about it, and it’s scary.”

Following directions from Bishop, I drove about four miles down the road from Van, where clear water devoid of odor flows freely from a natural spring. Locals call this “Spring Holler.” Even now, empty water bottles are clustered around the mouth of the spring, indicating recent use by locals.

“My dad and papaw all used that spring to draw water when they were young,” Bishop said. “It’s probably about the only water from here I’ll trust for awhile.”

Echoing Bishop, West Virginians' concerns about the safety of their water are now coming home to roost even for Gov. Tomblin. In a recent letter to the Federal Emergency Management Agency, Tomblin acknowledged that businesses are still continuing to lose a projected $1 million in daily revenue as they continue to depend on bottled water. In a stark description, recognizing the degree to which his constituents distrust local water supplies, Tomblin wrote:

"Many people no longer view their tap water as safe and are continuing to demand bottled water to meet their potable water needs. It is impossible to predict when this will change, if ever."

People Regulate the Mines

Dustin White, an organizer with the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition (OVEC), is now spearheading a bold campaign after the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) failed to do an adequate job regulating the coal industry.

The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA), passed in 1977, granted states an autonomous role in overseeing their own mining regulations, given that each coal mining state confronts different geography and topographical characteristics. White is helping organize a new effort called West Virginia Citizen Action for Real Enforcement (CARE), petitioning for section 733 of SMCRA to be used by the people to self-regulate – by getting the federal EPA to step in where the state DEP did not.

“The West Virginia delegation at the state and federal level is leading an onslaught on the state EPA to take away all regulatory authority,” White said. “We’re not asking the people to go to the DEP: we’re the citizens who are affected demanding the EPA take action.”

Coincidentally, almost two weeks before Freedom Industries’ spill of 4-MCHM, PPH and formaldehyde, CARE highlighted 19 specific instances of failed regulation by the state DEP in a 733 SMCRA petition. The federal Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE) is due to respond to five of those claims.

So far, the OSMRE has promised to investigate claims of the DEP failing to address flooding concerns in granting permits where storm water runoff is a factor; the DEP’s failure to issue SMCRA violations where harmful pollutants have been discharged; its failure to regulate selenium pollution; its failure to identify all of the harm to watersheds in its cumulative hydrologic impact analysis results, and claims that the DEP did not follow through on properly protecting soil in mandated reclamation efforts on mining sites. The recent tainting of water in nine counties may elicit even more investigations from OSMRE.

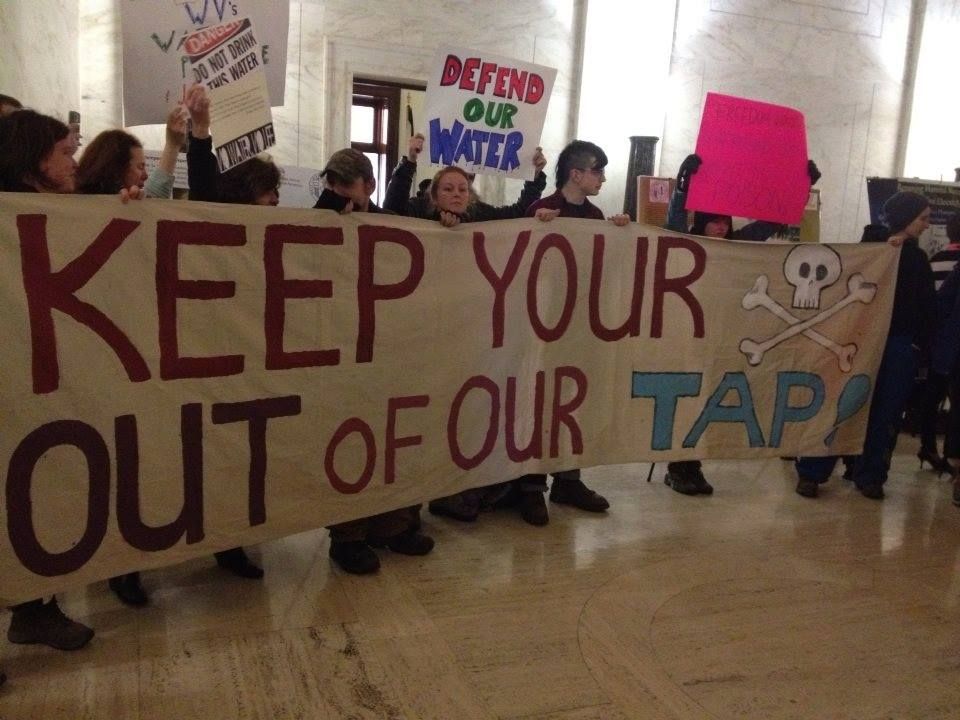

CARE is already getting West Virginians to take on the state’s regulatory apparatus. According to OVEC project coordinator Vivian Stockman, 2,000 signatures have been submitted in support of federal intervention into the DEP – whose head is appointed by the coal-friendly Gov. Tomblin. Activists also recently descended on the state capitol to deliver a letter to Tomblin’s office demanding a meeting with the governor to address their concerns with regulatory failure.

(Photo courtesy of WV CARE Campaign's Facebook page)

Failure of the Deregulation Agenda

Much like the case of the chemical plant that exploded in early 2013 near West, Texas, leveling that entire community, the lack of dutiful regulation of West Virginia’s chief industry ultimately led to the tainting of drinking water for 300,000 people in the state. The chemical storage facility recently acquired by Freedom Industries hadn’t been inspected since 1991. The chemical plant in West, Texas, hadn’t been inspected since 1985.

The explosion of BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil rig off the cost of the Gulf of Mexico in 2010 was also the result of a failed agenda of government deregulation – in that case, the Minerals Management Service under the Bush and Cheney administration, which was tasked with regulating the offshore oil drilling industry but actually allowed oil companies to fill in safety inspection forms in pencil, only to be sent back to federal regulators to go back over in pen. The MMS is also famous for a scandal in 2008 where members of an MMS regional office in Colorado were literally caught in bed with oil industry executives.

The facts are clear: incidents like the Elk River chemical disaster in West Virginia, the chemical fertilizer blast in Texas, and the BP oil spill in the Gulf will inevitably continue until state regulatory bodies can do their job, free of pressure from corporate conglomerates and the politicians they sponsor. Americans have a choice to make when it comes to governance – because as we now know, the next industrial disaster is just around the corner.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments