On Jan. 7 at around 11:30 a.m., two masked gunmen forced their way into the Parisian offices of the satirical weekly newspaper Charlie Hebdo and murdered 12 people, including editor Stéphane "Charb" Charbonnier. The murderers' cries of “Allahu Akbar!” left witnesses in no doubt as to the religious motivation of the crime. Another gunman then killed a Muslim policeman outside. Afterwards, the gunmen killed a policewoman in Montrouge and four hostages in a Kosher supermarket near Porte de Vincennes. An employee at a printing firm in Dammartin was also held hostage but survived. Police raided both premises and killed all three gunmen.

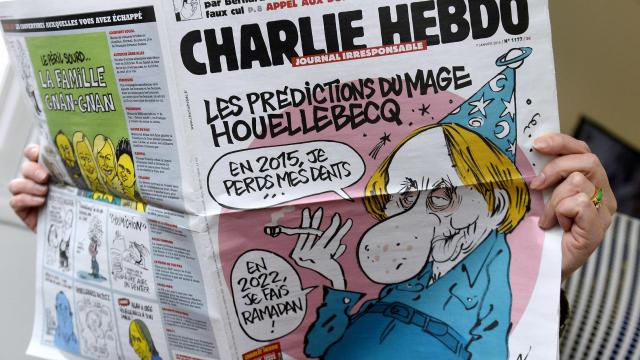

Despite its small print run of just 60,000, Charlie Hebdo is a household name across France. Taking advantage of the country's free press and overwhelmingly secular society, the paper prints controversial cartoons that have previously depicted anti-religious scenes including the Holy Trinity engaged in a sexual threesome, a Jew being accused of “shaving his brains” but not his sacred sidecurls, and Mohammed portrayed as a porn star.

Unsurprisingly, the paper's actions have invited criticism from religious communities. A 2011 issue of Charlie Hebdo, which was presented as “guest edited” by Mohammed and renamed “Charia Hebdo,” provoked a firebomb attack on the paper's headquarters – a chilling portent of what was to come. But Charlie Hebdo doesn't stop at religion. The publication ridicules pretty much everyone, from pop stars to politicians. Charlie Hebdo also received threats after lampooning France's far-right nationalist party, Front National – a group which, ironically, leapt on the massacre last week as an opportunity to promote its cause and earn new recruits.

I Am Not Charlie

Following the brutal killings at Charlie Hebdo headquarters, the phrase “Je suis Charlie” (“I am Charlie”) has been adopted as a worldwide slogan to show solidarity with the murdered cartoonists and journalists. People have taken banners bearing the words to vigils, displaying them on their Facebook profile photos and hashtagging them endlessly on Twitter. Newspapers have brandished them as headlines, and celebrity actors like George Clooney pronounced them at the Golden Globe awards over the weekend. Still, some have disagreed with the slogan, saying “Je ne suis pas Charlie” (“I am not Charlie”) while at the same time expressing deep sorrow over what happened.

One of those people is Albert, an IT consultant living in Paris. “This was an absolutely vile assault on human life,” Albert says, “but I despair at those jumping on the 'Je suis Charlie' bandwagon, most of them without having properly read Charlie Hebdo. How can a publication which shows the girls kidnapped and impregnated by Boko Haram's followers as benefit scroungers be something to support and celebrate?"

"Charlie Hebdo is a puerile, offensive publication. Muslims are already an unpopular underclass here, so why fan the flames like this? It's really important that we don't end up viewing those murdered as martyrs," he added. "I utterly condemn the murders but does that really mean I have to approve of everything in the paper? No."

Albert's friend, Leila, a fellow Parisian who works as a solicitor, and who is a Muslim, wonders: “Why are so many people so convinced that any criticism of the paper signifies some kind of sympathy with the killers or a 'they asked for it' mentality? It's entirely reductive and really, really stupid to think like that. I don't have to be Charlie to mourn the deaths of people who categorically didn't deserve to die."

"It's not just the depictions of Muslims in the paper I object to, either – not at all. I have no bias here. Charlie Hebdo is insensitive to so many groups. I'm just sad that so many unpleasant fights are now breaking out, particularly online, between people who feel the way I do and those who are vehemently pro-Charlie Hebdo. Something horrible has occurred and we should be joining together to try and find a way of preventing a repeat as well as ensuring that it doesn't cause even more problems in the already strained relationship between France's Muslims and non-Muslims,” Leila said.

Abi, a translator living in Brittany, disagrees with Leila and Albert's view of the paper. “It's important to be able to satirize extreme Islam,” she insists. “It causes a lot of harm throughout the world, the first victims of which are usually other Muslims. Let's not forget the 142 people, the vast majority children, murdered by Muslim extremists in Pakistan just before Christmas, or the 2,000 people feared dead in Nigeria in an attack by Boko Haram on Friday. Charlie Hebdo mocks all religions – it's part of the French militant atheist tradition. Also, attacking beliefs is very different to attacking a person for their skin colour – it's not racism.”

However, despite recognizing the devastating impact that fundamentalist Islam can have on the world, Abi believes the anti-Islam polemic that was already rife across France – and which has increased ten-fold since the attacks – is unfair to the majority of French Muslims.

"As a student in Lille, I formed strong friendships with Muslim fellow students, and I believe the vast majority of Muslims in France are peaceful people: pious, respectful and friendly," she says, "very different to how they are depicted by the National Front, and some of the media. There were some Muslims I never managed to talk to, who ghosted around the halls in long robes, baggy trousers and long beards. The others explained that they were Salafist Muslims and they are pretty extreme, and since I was a woman they probably wouldn’t ever say hi. Of the 400 or so people who lived in those student halls, there must have been one or two Salafists – a minority.”

Caroline comes from Nancy and says she is looking for work in the radio sector. “I'm a Catholic,” she explains, “and I wasn't shocked by the Jesus cartoons. We have a history of freedom of expression in this country and I've grown used to that.”

Lawrence, a French video editor living in London, says: “As a child I wanted to be a cartoonist, and I've met and interviewed Charlie Hebdo cartoonist Luz, who fortunately survived the attack. I hear some of my friends who I considered to be progressive saying they are shocked by images from Charlie Hebdo and consider them 'racist.' Taking the pictures totally out of their context, ignoring the fact that the whole magazine is published in a certain country with a certain cultural background and references, is ridiculous. Charlie Hebdo fights against all kind of powers, whether political, religious or ideological. They were bashing Muslims a lot recently because some of them are getting more and more powerful and dangerous.”

France's two main Muslim organizations, Le Conseil Français du Culte Musulman (French Islamic Board, or CFCM) and L'Union des Organisations Islamiques de France (Union of Islamic Organizations of France, or UOIF) have officially condemned the attacks and called on Muslims across the country to do the same. In a statement, they called for “secular training” for imams to prevent “the influence of self-proclaimed imams.” But while the CFCM falls clearly under the umbrella of those who have condemned the crime, at the same time the group doesn't support the publication. In February of last year, some of the groups that form part of the CFCM took Charlie Hebdo to court over a front page that bore the legend: “The Koran is shit, it doesn't stop bullets.”

Following the gruesome denouement, and a nationwide march by millions over the weekend that was the largest demonstration in France in a generation, the dust is still settling from last week's massacre. Now, people await dialogue, which is expected to emerge over the next weeks and months, to begin to understand how the event will affect cultural relations, religious tolerance and the shape of the free press moving forward. tags: Charlie Hebdo, Charlie Hebdo massacre, Je suis Charlie, Je ne suis pas Charlie, Islamic extremism, press freedom

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments