Here at the Paris climate summit, the big news is that the final agreement governments hope to sign by week’s end may urge limiting temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius. This would represent a major shift from the current international goal of 2 degrees C as well as a historic – and surprising – victory for the world’s poor and most vulnerable nations.

Their representatives, joined by climate justice activists, have long criticized the 2 degrees C goal as a virtual death sentence for millions of people already suffering from the sea-level rise, harsher droughts, and other impacts unleashed by the 1 degree C of temperature rise measured to date.

“If it were New York City or London that was disappearing beneath the waves like some of these Pacific Island states are, I guarantee you there wouldn’t be any debate about 2 degrees versus 1.5 degrees,” Kumi Naidoo, executive director of Greenpeace International, told The Nation. “We need to set an official target of 1.5 C, challenging as it will be to meet it, in order to save as many people as possible.”

Previously dismissed by most wealthy countries as economically unrealistic, the 1.5 degrees C target has reemerged at the Paris summit due to a confluence of factors: increased recognition by many wealthy countries that even 2 degrees C will bring ruinous changes to food, water, and other vital systems; a more unified diplomatic posture on the part of the 100-plus poor and highly vulnerable countries on record supporting a 1.5 degrees C target; and relentless pressure from civil society.

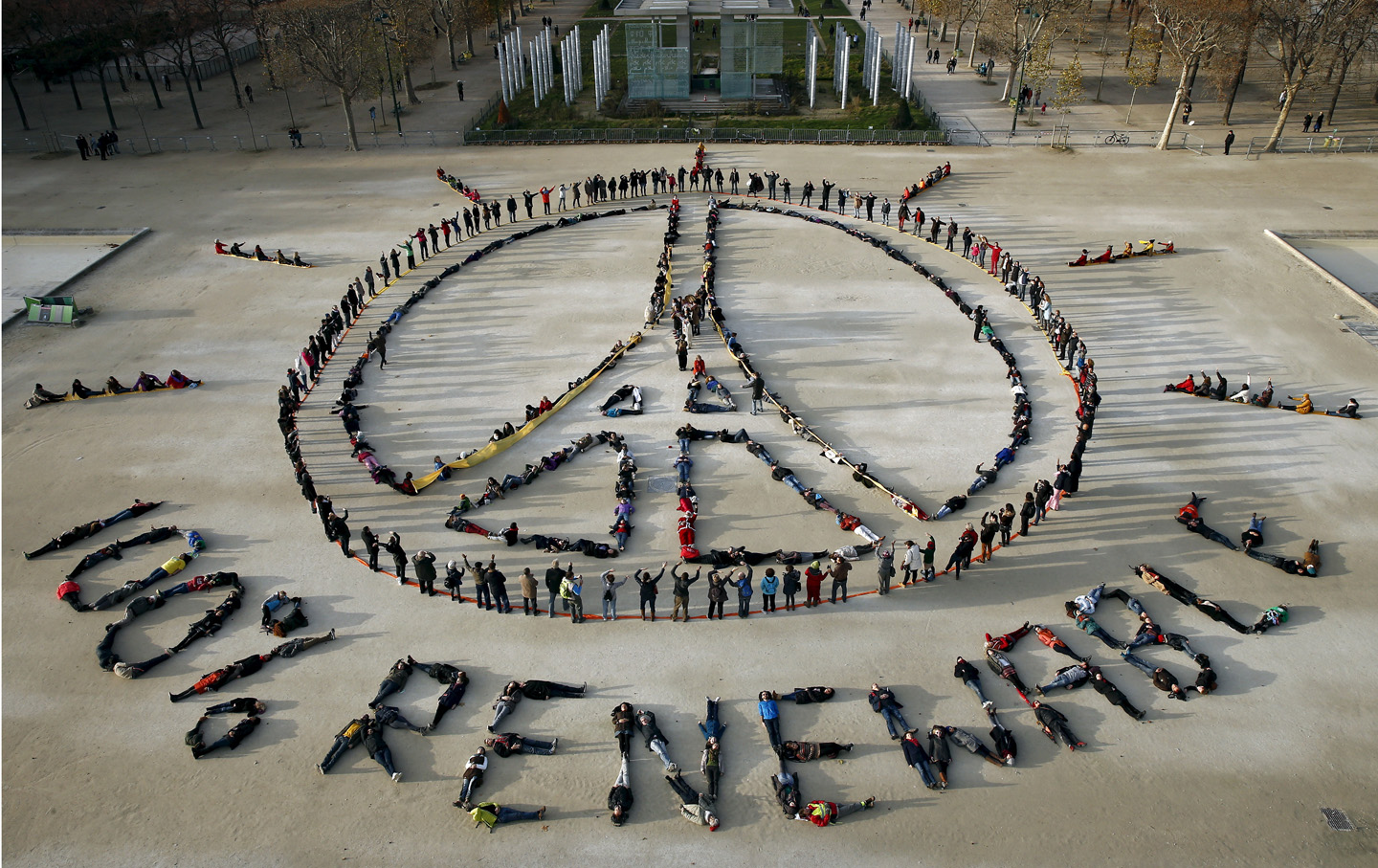

Civil society has been creative, outspoken, and even boisterous during the first week of the UN climate summit, despite the official ban on large public gatherings that canceled a massive march intended to greet world leaders arriving a week ago. If pressure is sustained during the second and final week of negotiations, said former heads of state, business executives, and climate-justice activists on Sunday, the summit could end up endorsing a long-term target of 1.5 degrees C, an agreement of unprecedented ambition.

After French authorities banned large outdoor marches in Paris following the November 13 terrorist attacks, climate activists accepted the decision but quickly devised alternative methods of making their voices heard. Thousands joined hands to form a human chain along the two-mile route of the cancelled march, while hundreds of thousands of people demonstrated in cities around the world. Also in Paris, activists placed an estimated 20,000 shoes in the Place de la République to symbolize people who were prohibited from marching. Pope Francis donated plain black dress shoes; Ban Ky Moon, the UN secretary-general, donated a pair of jogging shoes.

On Saturday, Nation contributors Bill McKibben and Naomi Klein hosted a mock trial of ExxonMobil at a “People’s Climate Summit,” held in the Parisian suburb of Montreuil. The next day, activists carried 196 office chairs through the square facing the Montreuil city hall – chairs that had been “liberated” from banks throughout France. “These chairs were requisitioned to reveal the links between the tax evasion practiced by big banks and the lack of funding needed against climate change, particularly the $100 billion a year for adaptation that wealthy countries have promised poor countries but that has been blocked by financial elites,” said Cindy Wiesner of the Grassroots Global Justice Alliance.

“Thirty trillion dollars disappears every year into the black hole of tax havens that these banks control, tax havens that benefit criminals and murderers – drug cartels, gun traffickers, and the banks themselves. These 196 chairs represent the 196 countries whose people deserve a seat at the table for a just global economy.”

“We need civil society to keep the pressure up for the rest of this week,” Mary Robinson, the former president of Ireland, said Sunday in remarks to a “Development and Climate Days” conference urging “zero poverty, zero emissions.” “We need to remind negotiators of what world leaders said in their speeches on Monday, which was very good,” said Robinson, who now heads the Mary Robinson Foundation for Climate Justice. “It was about ambition, it was about people, it was about justice.”

The French president, François Hollande, for example, said, “We cannot accept that the poorest countries, those with the lowest greenhouse gas emissions, are the most vulnerable. It is therefore on behalf of climate justice that we must act.” Hollande added that temperature rise must be limited to 1.5 C “if possible.”

Two days later, Jochen Flasbarth, the state secretary of Germany’s Ministry of the Environment, said the 1.5 C goal “must be mentioned” in the summit’s final agreement and confirmed that this was the official position of the German government, reported the online news service Climate Home. Thus the 1.5 C goal has now been endorsed by the host nation of the summit as well as Europe’s strongest economy.

On Monday, a delegation from the European Parliament came to the summit to support a 2 C target, but “1.5 C is obviously a better target,” said Matthias Groote of Germany, the spokesperson for the environmental group of the delegation. Stressing that he was not authorized to take a position for the European Parliament as a whole, Groote added that, “personally, of course I would prefer a 1.5 C target. At the end of the day, it will not be as expensive as the 2 C target, so if we can achieve a global agreement on this, let’s grab that chance.”

Also on Monday, Todd Stern, the chief U.S. negotiator in Paris, reaffirmed that the United States has heard the concerns of poor and vulnerable nations and is open to adjusting the final text regarding the 1.5 C goal. “The goal isn’t going to change, the goal is to hold the temperature [rise] as far below 2 degrees as possible,” Stern told a press conference at the Le Bourget convention center. “We are working with other countries, with our island state friends and other developing countries, and developed countries, on language toward that end.”

The agreement taking shape in the lead up to the Paris summit was “not good enough,” as it would produce at least 3 degrees Celsius of temperature rise by 2100, Robinson told The Nation. But the world is capable of much better, she added, noting that she had just attended an event where top business executives had pledged that their companies would achieve zero net carbon emissions by 2050.

“Carbon neutral by 2050, we will have 35 years to get there,” Richard Branson, the CEO of Virgin, said at the event organized by the self-described B Team Robinson referenced, which includes Unilever and Marks & Spencer. “It’s actually just not that big a deal,” Branson continued, “but we need clear long-term goals set by governments this week. Give us that goal and we will make it happen.” The B Team contends that putting the world on track for zero net emissions by 2050 would also “keep the door open” to eventually limiting temperature rise to 1.5 C.

Also giving credence to the possible adoption of the 1.5 C goal in any agreement this week in Paris was Saleem ul Huq, a scholar and activist who directs the International Center for Climate Change and Development in Bangladesh. Huq has trained many of the diplomats representing the 48 Least Developed Nations at past climate summits, and he remains privy to their deliberations.

“I foresee that we will get an agreement including the 1.5 C goal,” Huq told The Nation. “Nobody wants to walk away from Paris without an agreement, neither the rich countries nor the poor countries. The Least Developed Countries have a clear position: World leaders must agree to support and protect all of the people on earth, not just some of them. The language that rich countries are now offering would commit the world to a long-term goal of keeping temperature rise ‘well below 2 C.’ Poor countries, though, are insisting that the long-term goal must be 1.5 C, and I think they’ll get it. President Obama and most world leaders seem receptive to this language, and we’ll spend the next week beating up on any other nations that try to block it.”

In the United States, mainstream media focused on war, terrorism, and presidential politics are paying relatively little attention to the Paris summit. Sunday’s online edition of The Washington Post carried five lines about the summit; the Sunday New York Times ran a single article. Mainstream European media are much more engaged; The Guardian in particular is providing in-depth, timely coverage.

Meanwhile, activists are relying on social media to spread their message. Huq noted that the 1.5 C goal already has its own hashtag, #1o5C, which he said supporters have been tweeting along with selfies of the 1.5 C hand signal: The pinkie of the right hand forms the 1, the other four fingers are circled to form the decimal point, and all five fingers of the left hand are spread to make the five. As he demonstrated the gesture for a reporter, Huq broke into a beaming smile.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments