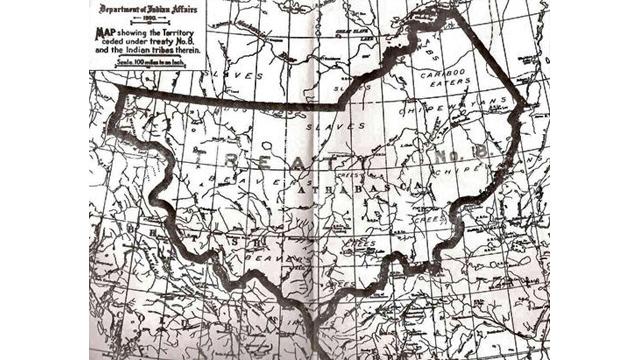

Photo: Map showing the area covered by Treaty 8.

Fort Chipewyan is a small indigenous community on the edge of vast Lake Athabasca in Alberta’s remote north, accessible only by plane in summer and by snow road in winter. The town is directly downstream from the Alberta tar sands—Canada’s wildly lucrative, hotly debated, and environmentally catastrophic energy project.

Residents say that tar sands mining is not only dangerous but illegal because it violates the rights laid out in Treaty 8, an agreement signed in 1899 by Queen Victoria and various First Nations. Their legal challenge to the tar sands project could have a powerful impact on the legal role of treaties with First Nations people.

It should come as no surprise that Fort Chip’s relationship to the tar sands industry is a contentious one. Being first in line downstream means that residents are the first to feel the effects of pollution: poisoned water, air and animals. The deformed fish with bulbous tumors that residents pull from Lake Athabasca are legendary, as are the stories of Fort Chip’s abnormally frequent cases of rare forms of cancer.

The Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation (ACFN), many of whose members live in Fort Chip, responded on October 1 with a landmark constitutional challenge to Shell Canada’s expansion of its Jackpine tar sands mine. The challenge states that the expansion would be a further assault on their rights as First Nations people, which are federally protected under Treaty 8.

The Jackpine expansion, which will be reviewed at the end of the month, would destroy over fifty square miles of land and begin mining portions of the Muskeg River in Canada’s most important watershed. AFCN members point out that both the federal government and Shell have ignored their legal duty to consult with them. This time, they’re going to fight back.

“As long as the sun shines”

As indigenous people, the relationship with the land sustains the Chipewyan: the plants and medicines they gather, the moose and fish that form the basis of the traditional diet, the water from the lake, and the deep spiritual connection with this particular place. Land is the basis for culture and identity; when the land is destroyed, so are the people.

When the threats to health and traditional ways of life associated with tar sands mining are lamented, what’s often missing is the recognition that the mining is also in violation of Treaty 8. The Treaty, which covers an area twice the size of California within northern Alberta and neighboring provinces, guarantees basic rights such as health care and education, as well as the right to pursue traditional ways of living, including trapping, hunting, and harvesting.

If the government does decide to reduce the amount of land used for these activities, it has a duty to consult with and accommodate the affected First Nations. According to the treaty itself, this agreement will remain valid “as long as the sun shines, the grass grows, and the rivers flow.” So, forever—in theory.

Treaty 8—along with the ten other treaties that were signed a hundred years ago and supposedly guarantee the continuation of native ways of life—isn’t supposed to have an expiration date. But the treaty’s language begs the question: what happens when the sun no longer shines because it’s obscured by smog? When the grass has been turned into an open pit mine, and when the rivers no longer flow because that water is siphoned off for bitumen processing?

If the original signatories had known that this remote outpost would be turned into a smoke-belching Mordor, it would probably have raised some eyebrows. On both sides.

Wide repercussions for native land rights

Chelsea Flook of the Sierra Club, which works closely with AFCN, is hopeful about the case. No constitutional challenge based on Treaty 8 rights has ever been fully argued before a judge, she says. It’s a test case that, if successful, could set a precedent for stricter enforcement of treaty rights and change the way industrial development is regulated. More importantly, though, it would embolden indigenous groups all over the Canada to fight abuses by both industry and government.

For those of us in the United States, the gains and losses of a tiny native community, closer to the Arctic circle than most of us will ever get, may seem remote. But what’s at stake here isn’t just a few hundred people’s ability to hunt moose and conduct ceremonies in a particular spot. Both the U.S. and Canada share a history of colonizing what is essentially stolen land; our societies were built on a common system of disenfranchisement.

Honoring the treaties means honoring the most basic of agreements: the protection of a way of life—and, by extension, life itself. In the years since that day in 1899 when Treaty 8 was signed, every attempt to erase or assimilate indigenous people has been made, regardless of any commitment on paper. Native language and culture have been criminalized, children have been relocated to residential schools, and genocide has been a government policy. Industrial destruction of land is one final assault.

It’s a brutal and violent history, one that’s not taught in school. Coming to terms with our own past—as Canadians, as Americans, as colonizers—is unpleasant. It means seeing ourselves, here and now, in an unflattering light. Honoring agreements such as Treaty 8 means acknowledging all the ways these documents have been violated.

With this constitutional challenge, AFCN is forcing the Canadian government to look in the mirror. It’s a small step with huge implications, and a starting point for redressing more than a century of broken promises.

Kristin Moe is a writer and climate justice activist from the U.S., spending three months in Alberta writing about the social and cultural impacts of the tar sands.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments