Earlier this month, the trustees of the city graveyard in Santa Monica, California (final resting place of actor Glenn Ford and tennis star May Sutton) announced they were selling their million dollars' worth of stock in fossil fuel companies. As far as I know they were the first cemetery board to do so, but they join a gathering wave of universities, churches and synagogues, city governments and pension funds.

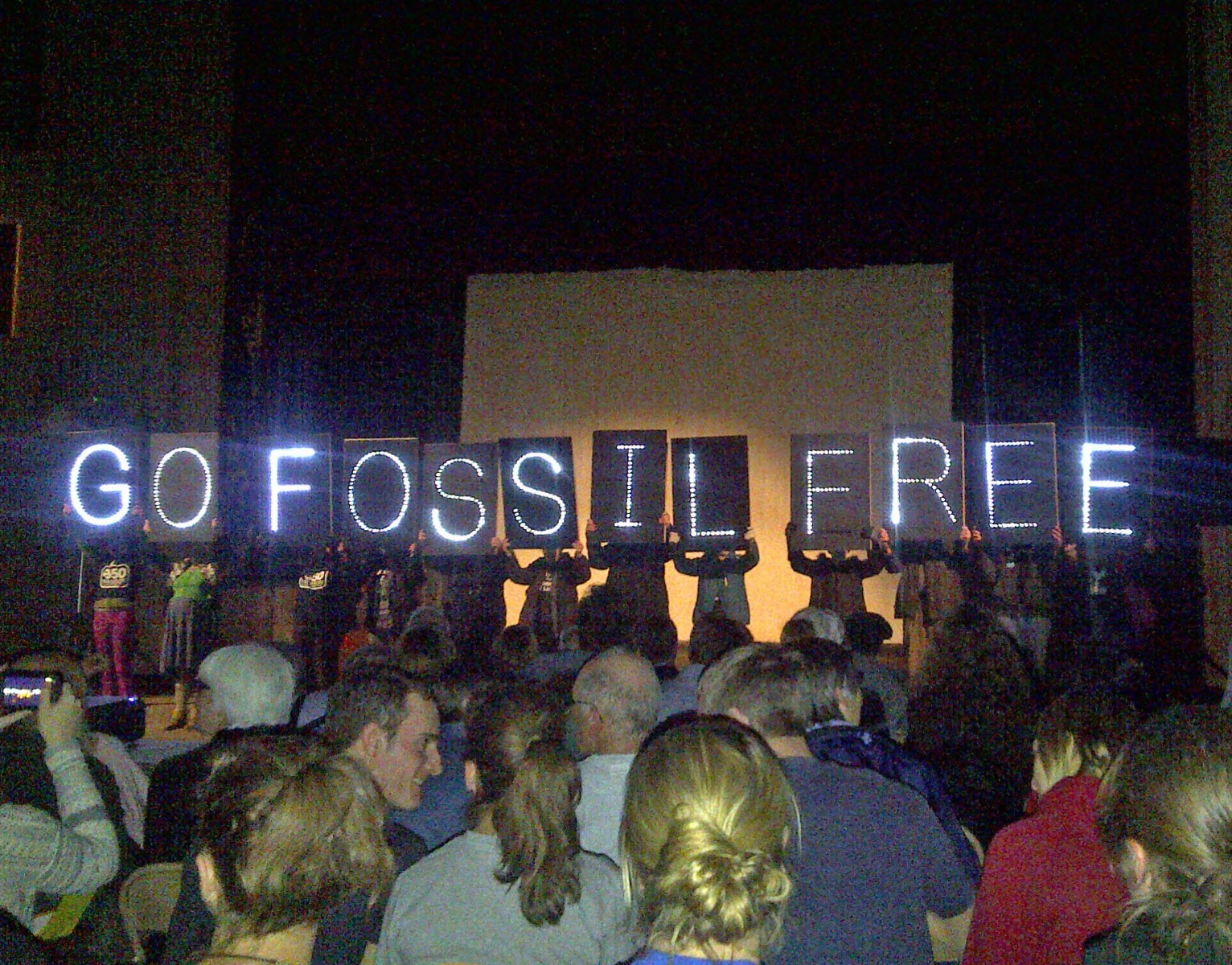

In the last few months, fossil fuel divestment has turned into one of the fastest-growing protest campaigns in recent American history – and it’s already reached all the way to Australia, where portions of the Uniting Church have announced they’ll sell their fossil fuel stock as well.

It’s happening because it’s one of the few ways for concerned people and institutions to take a stand on climate change, and confront the enormous power of the fossil fuel industry. But it’s also happening because once you run the numbers, there’s no way to escape the conclusion that this industry is now an outlaw industry. Not outlaw against the laws of the state – they generally have a large hand in writing those – but outlaw against the laws of physics.

Here’s the math: almost every country on earth, including Australia, has signed on to the idea that we shouldn’t raise the planet’s temperature more than two degrees – that was the only tangible outcome of the otherwise pointless Copenhagen conference on climate change in 2009. The one degree we've raised so far has already melted the Arctic, not to mention laid the ground for Australia’s "angry summer." As such, two degrees is too high but it’s the only red line the planet’s governments have ever agreed to.

We know roughly how much more carbon we can emit before we go past two degrees: about 500 billion tons. And at current rates of emissions, that will take us less than 40 years. But the math gets really impossible when you consider how much carbon the world’s coal, oil and gas industries already have in their reserves. That number is about 2,800 gigatons – five times what the most conservative governments and scientists on earth say would be safe to burn.

And yet, companies will dig it up and burn it – that’s what their business plans call for, that’s what their share prices depend on, and that’s what their government lobbying budgets are spent on making sure happens. Once you know the maths, you know that Exxon, Rio Tinto and Shell and so on aren’t like normal companies – they’re really rogues. But you also know that our situation is hopeless unless we get to work: the end of this script is written, unless we rewrite it.

Doing so is hard. It requires changes in our personal lives and in our government policy, which Australia has begun to make: the carbon tax, if it survives the next election, is a serious step forward. It also requires that we rein in the plans of, say, those coal companies that want to mine places like the Galilee Valley: if the expansion plans of Australia’s miners are carried out, that coal alone will use up almost a third of the atmospheric space between us and those two degrees.

There are a dozen other places like the Australian coalfields around the world, and we have to stop them all. The fossil fuel industry should be turned into an energy industry: we have to take the hundred million dollars a day that Exxon spends on finding new oil, and have them spend it on solar panels instead. Which is why, for now, we have to divest those stocks.

The idea is not that we can bankrupt these companies; they’re the richest enterprises in history. But we can give them a black eye, and begin to undermine their political power. That’s what happened a quarter century ago when, around the western world, institutions divested their holdings in companies doing business in apartheid South Africa. Nelson Mandela credited that as a key part of his country’s liberation, and Desmond Tutu last year called on all of us to repeat the exercise with the fossil fuel companies.

It will be even harder this time, since this is such a dug-in industry. But their ability to use all those reserves is limited because of climate change, HSBC bank predicted share values of fossil fuel companies would fall by half or more. An investment in a fossil fuel company is a wager that we’ll never do anything about climate change, because if we ever even tried to meet that two degree target, those stock values would plummet.

It makes no sense to pay for one’s pension by investing in companies that make sure we won’t have a planet to retire on. Even the dead won’t rest easy if their perpetual care is paid for at the cost of those they left behind – so ask your church, your super-annuation fund, and even your cemetery which side of this wager they’re taking.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments