Like the majority of the nearly 750,000 people stuck in local jails across the United States, Rebecca Snow was not held in the Ascension Parish jail in central Louisiana because she had been convicted of a crime. The 33-year-old mother of three, who was charged with two nonviolent misdemeanors in late August, simply could not afford to post bail.

If Snow had the $289 set for each charge, she could have gone home to her family instead of sitting in jail. Many others arrested in the parish are able to post bail and go home, but Snow didn't have the extra cash: She relies on public assistance and is indigent, according to a civil rights complaint filed against the parish's sheriff and top judge.

The U.S. Supreme Court and the Justice Department have both said that incarcerating someone solely because they can't afford to post cash bail is unconstitutional, but that was the policy in Ascension Parish until just a few weeks ago.

Ascension sheriff deputies would set bail during booking using a court-issued "schedule" that matched the alleged offense with a generic bail amount, and some arrestees waited days before seeing a judge who could hear a motion to reduce it, according to the complaint. No individual factors such as prior record or employment were considered, and even those arrested for minor crimes like traffic violations were not released without posting bail.

In early September, civil rights attorneys filed a class-action lawsuit challenging the bail scheme, with Snow as the lead plaintiff. A settlement was reached within weeks. Now those arrested for misdemeanors in Ascension Parish are released on their own recognizance unless they are charged with assault, drunk driving or a list of other crimes that generally involve putting other people in danger. A judge must promptly set an individualized bail for those who are jailed.

"[The defendants] don't really have any arguments," said Alec Karakatsanis, a cofounder of Equal Justice Under Law, which worked with the MacArthur Justice Center in New Orleans to challenge Ascension's bail policy. "It's a terrible policy in addition to being illegal. It's expensive and it ruins people's lives and it devastates them."

Nationally, jails have twice the admission rate of state and federal prisons, and 62 percent of those locked up have not been convicted of any crime and are legally presumed innocent, according to the Vera Institute of Justice. Three out of four people in jail are being held on nonviolent traffic, drug, property or public order charges. In most jurisdictions, poor people facing minor charges are forced to stay in jail or plead guilty to get out while those who have money on hand often go free.

Using the Constitution to Force Local Reforms

Since January, Karakatsanis and local partners have filed lawsuits challenging secured money bail programs in seven cities across the South, and so far defendants in six cities quickly settled and agreed to end the practice of requiring bail for nonviolent misdemeanors. The first lawsuit, filed against the City of Clanton, Alabama, attracted a statement of interest from the Justice Department declaring that jailing people solely because of their poverty violates the US Constitution's equal protection clause and is simply "bad public policy."

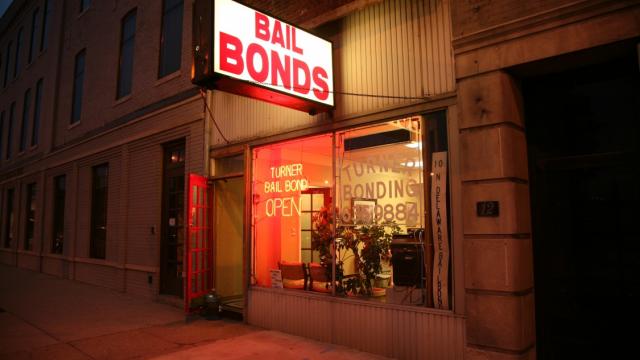

Suing individual officials and jurisdictions has proved to be an effective tactic for civil rights advocates who argue that many of the nation's 3,000 jails have become modern-day debtors' prisons. Attorneys like Karakatsanis are going from county to county to shut down illegal secured money bail and court fine collection schemes that fill courthouse coffers and keep private collection companies and bail bondsmen in business while poor defendants, who often cannot afford child care or to miss even a day of work, are caged without being convicted.

"We are going from jurisdiction to jurisdiction and asking them to change, and if they don't, we certainly sue them," Karakatsanis told Truthout. He added that his group would be filing more lawsuits across the country.

By definition, bail is not a fine or a form of punishment. The purpose of bail is, in theory, to ensure that arrestees show up to court. If you are jailed and a bail is set, you may wait there for weeks, months or even years for your trial to start - or you can post bail, which will be refunded when you appear before a judge. In some parts of the country, if you don't have the money, you can hire a bail bonds agent to post bail for a fee, usually at 10 percent of the bail amount. You don't get that money back even if you are found not guilty. (In the few states that have outlawed for-profit bail bond agents, a secured bond may sometimes be paid at 10 percent of the set amount as well.)

Money bail tips the scales of justice in favor of those who have cash on hand. For arrestees who can't afford to put money down on their own freedom, jail makes it much more difficult to escape the deep maze of the criminal legal system. The Vera Institute reports that even spending as few as two days in jail can reduce economic viability, promote future criminal behavior, degrade personal health and increase the chance that a defendant is incarcerated if found guilty.

Pretrial incarceration also increases the likelihood that people will take a plea deal, and some people plead guilty to crimes they didn't commit just to go home and avoid losing their jobs and contact with friends and family. That's one reason why activists in Massachusetts, New York City and Chicago have organized community bail funds to free low-income people from jail. Since bail money is generally returned once defendants appear in court, these grassroots bail funds can extend the benefits of a recyclable resource to many people who would otherwise be left to defend themselves from a position of incarceration.

Exposing the Bail Bond Lobby

Cherise Fanno Burdeen, director of the Pretrial Justice Institute, said advocates have spent the past five decades working with courts and jails to replace secure money bail with pretrial risk assessments and programs that release defendants under supervision - only to see the number of people in jail skyrocket and illegal bail schedules become the norm in many jurisdictions. This has come at a significant cost to taxpayers, not to mention the very notion of liberty, so why haven't judges and lawmakers been eager to move away from using money as bail?

"Someone is making a living off of this," Burdeen said. "The commercial [bond] lobby has worked very hard to maintain bond schedules to make sure that financial conditions for release are set at to as many charges as possible."

Burdeen said the bail bond industry isn't just "mom-and-pop shops on the corner," and only 13 insurance companies underwrite the billions of dollars worth of bonds issued every year. From 2002 to 2011, the bail industry made $3.1 million in donations to state-level lawmakers to influence pretrial detention policies, according to Justice Policy Institute. Burdeen said that bond agents enjoy a lucrative business model that allows them to make political contributions to influence local elections as well.

The bail industry is even suspected of paying the Southern Christian Leadership Conference - the group founded by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. – to lobby against legislation in New Jersey that established non-monetary alternatives to cash bail for low-level offenders. The group's opposition sent civil rights leaders' heads spinning because cash bail is considered to be a major reason why Black people are jailed at a rate nearly four times that of white people.

Despite pushback from the bail bond industry, New Jersey successfully passed the legislation into law, and similar reforms have been achieved in Kentucky, Colorado and Washington, DC. In New York, a Democratic lawmaker introduced legislation earlier in October that would abolish money bail in that state and give judges the option of either releasing arrestees on their recognizance, releasing them under pretrial monitoring or remanding them to a correctional facility.

Burdeen said state-level reform is gaining traction, and on October 22, her group launched a national campaign called 3DaysCount to bring similar reforms to 20 more states by 2020. The campaign promotes "cite and release" policies for low-level misdemeanors and replacing cash bail with "preventative detention" hearings where prosecutors must prove that a defendant is a threat to the community in order to hold them in jail.

In the meantime, Karakatsanis and his colleagues will continue to crack down on illegal bail schemes in individual jurisdictions while building a mountain of case law that can eventually put an end to the current wealth-based bail system once and for all.

"Certainly the way we do money bail in every jurisdiction in the country is unconstitutional," Karakatsanis said, adding that the fixed bail schedules in places like Ascension Parish are not the only bail schemes that are unconstitutional. "On principle it is unconstitutional to keep a human being in a jail cell simply because she can't pay to get out."

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments