The 2016 Bernie Sanders campaign for the Democratic nomination excited millions because the senator spoke to the challenges facing a large number of Americans and proposed solutions that went beyond the tortured mainstream consensus about the limits of what is possible, a consensus that has plagued democratic politics since at least the 1980s. In promoting universal healthcare, living wages and free education, Sanders argued, and continues to insist, that the richest country in the world can afford to provide these basic supports to everyone.

Sanders’ ideas, along with those of Elizabeth Warren and other strong progressives, are basically FDR updated for the 21st century: significant redistribution of income, universal health insurance, living wages, and free education among other supports. No doubt, implementing these proposals would amount to enormous changes in the U.S., but they are also conservative in the sense that Sanders is essentially proposing to keep the economy we have and legislate a more equitable distribution of the gains.

What he is not talking about is a more thoroughgoing transformation of the economy that would democratize wealth and how it is created. While livelihoods would be much better under a progressive Democratic administration and Congress than they are now, the political power imbalance that derives from the vast inequality in wealth would constantly threaten to reverse the redistribution that Sanders and others are calling for, as has been happening since the early 1980s. Simply put, to actually change the balance of power in a lasting way, we need to take on the massive inequality in wealth that underlies it.

For ideas about how to effect such a transformation, we can look across the Atlantic to the United Kingdom, where the Labour Party under Jeremy Corbyn is proposing major structural changes in how the British economy works. These changes directly address the ownership and control of productive assets. Similar ideas are bubbling up from the local level in the U.S., but there is no national leadership or a clearly articulated agenda for such sweeping changes in this country.

What is Labour’s program? The 2017 Labour Party Manifesto, titled “For the Many, Not the Few,” outlines the general approach and describes the relevant policies. Additional reports on key elements including an industrial strategy, a national investment bank, alternative models of ownership and the creation of a national education service fill in many of the details.

The term “industrial strategy” is largely foreign to American policy makers, although the U.S. does actually have such a government-led strategy that supports the military and aerospace industry to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars a year. The U.S. also subsidizes fossil fuel exploration and from time to time there are calls for major public investments in infrastructure. So, while we rarely use the term, the concept is already applied in major sectors of the U.S. economy.

For Britain, Labour proposes a large, multi-faceted industrial strategy that includes major public investments in research and development; education; infrastructure of all types; various hi-tech sectors; and renewable energy technology and production with aggressive goals for converting to low- and zero-carbon energy production.

In addition, the Manifesto is very explicit about directing investments toward regions suffering from economic stagnation in order to create a more balanced economy with greater participation by all. In order to direct these investments equitably throughout the country, the party envisions the creation of a network of regional development banks, under the umbrella of a national investment bank.

One of the more politically transformative proposals concerns the role of business and its relationship to government. Labour wants to make significant changes to how business operates in order to protect workers and their livelihoods and to make sure that the benefits of economic growth are widely shared. To this end, Labour proposes to amend business law so that decisions are made with all stakeholders in mind, not just the shareholders. Other stakeholders include workers and the communities where businesses are located. Likely environmental outcomes also go into development decisions.

There are other pro-labor innovations in the Manifesto. One provision mandates that when the owners of an enterprise decide to sell, employees must be given the option of acquiring it themselves as owners. Another provision deals with pay inequality between management and workers with limits set on the difference between owners and employees – especially for firms that contract with the government.

Perhaps the most innovative elements of the Labour Manifesto are the plans around alternative models of ownership. A special report on these models starts by describing the problems caused by the wholesale privatization that got underway with Margaret Thatcher:

The predominance of private property ownership has led to a lack of long-term investment and declining rates of productivity, undermined democracy, left regions of the country economically forgotten, and contributed to increasing levels of inequality and financial insecurity.

More specifically, the dominance of private property gives investors rights to appoint management in business and to control profits – control that, according to the report, is “not necessarily beneficial to society.” Instead, new ownership modes can encourage long-term planning, reverse the productivity declines over the past decade or more, democratize economic decision making and share the gains more evenly.

Cooperatives are one of the key forms of ownership discussed in the report. There are many types of cooperatives, but in the manufacturing and service sectors, cooperatives are characterized by joint ownership and management by the workers. By democratizing ownership and management, as well as control over profits generated, cooperative enterprises ensure that the benefits are more widely shared in society and that the contributions of labor are fully valued.

The report calls for doubling the size of the cooperative sector in the UK over the next decade, which in absolute terms, while challenging, will not have a large impact on overall employment levels. Still, it would be a good start and allow for further growth and development. The report devotes significant attention to more advanced cooperative federations in Spain and Italy, clearly pointing to those as positive models that should be emulated over the long-term in the UK.

The report also calls for devolving decision making to communities. In some cases municipalities would own and control enterprises to allow greater worker and community input into management decisions. The result would be that wealth generated in a community would be much more likely to remain there.

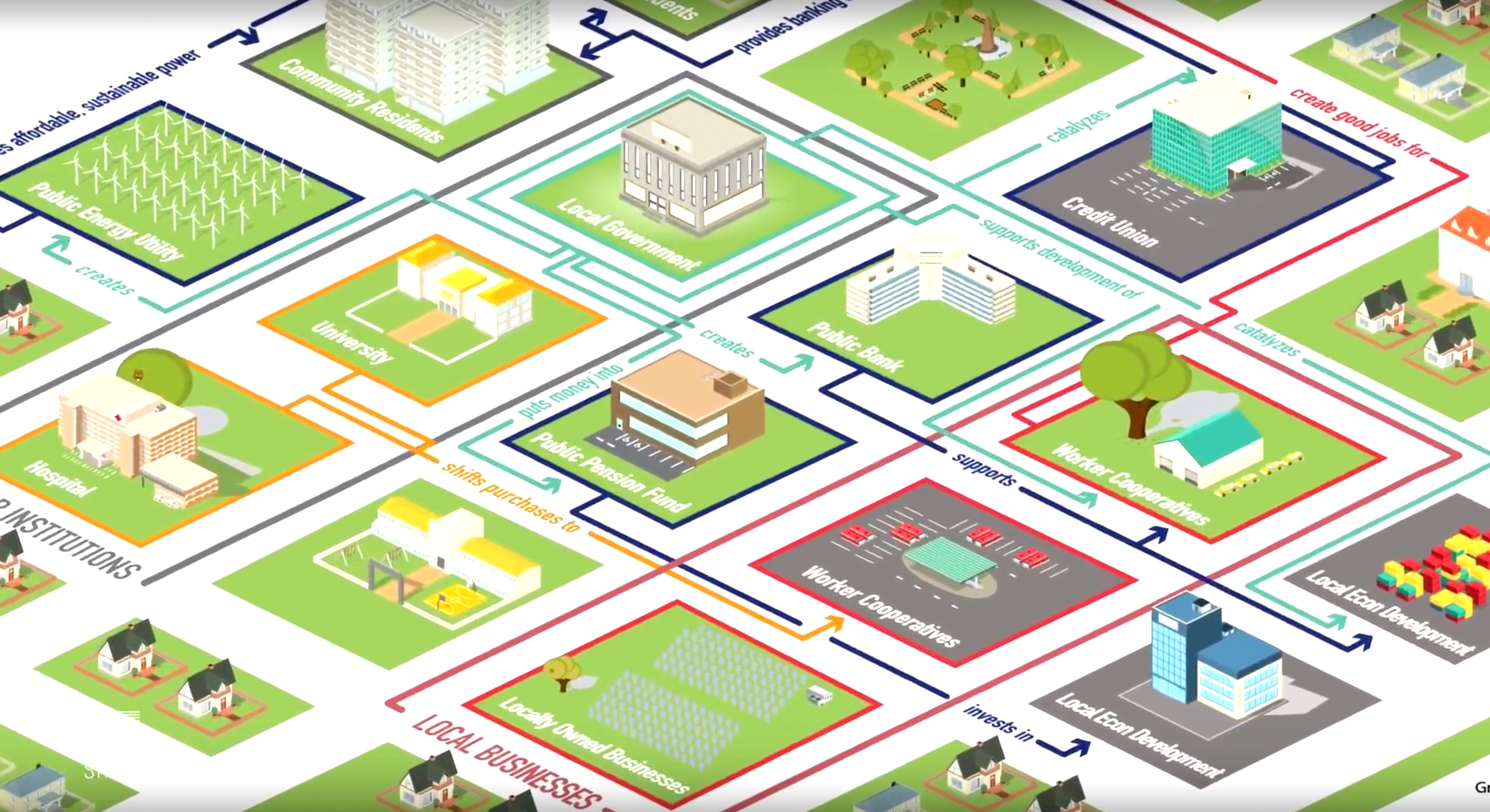

Community wealth-building can be greatly enhanced by “anchor institutions,” large publicly owned institutions such as universities, hospitals and city governments that source goods and services from the community itself. Anchor institutions can provide a stable market along with support systems such as credit, education and technical expertise.

One prominent example in Britain is the small city of Preston, in which the municipality works with anchor institutions to buy goods from local businesses and cooperatives. This initiative, instituted at the height of a period of austerity and economic stagnation, succeeded in creating economic dynamism where little had existed previously. It’s a model similar to and inspired in part by the Evergreen Cooperativesin Cleveland and developed in cooperation with the U.S.-based Democracy Collaborative, which was also instrumental in developing the Cleveland model. You can watch this new video on The Laura Flanders Show to learn more.

What is slightly unique in Preston is the role played by government in uniting local businesses in a type of economic decision making that prioritizes the local economy and values investing for longer-term benefits instead of making sourcing and sub-contracting decisions solely on the basis of price. Although the Preston experience is just one case, the results have been positive enough – even without a Labour government in power – for Labour to make it a pillar of the party’s overall economic development strategy. With “Prestons” all over the country funded by public development banks, local economies would be strengthened while economic decision making and benefits would be democratized.

Taken together, all of these elements are designed to empower workers and communities to participate fully in generating economic development as well in receiving full and fair returns for that participation instead of allowing corporations and the ultra-wealthy to monopolize those processes.

At the moment, Labour is, in the words of Joe Guinan and Martin O’Neill, co-authors of a recent analysis in the British Journal Renewal, “a radical democratic socialist government-in-waiting.” The Party has not taken power yet and will likely have to wait a few years for elections and a chance to gain a majority in Parliament. In the meantime, the activist wing of the party will continue developing ideas and building the vital intellectual and policy infrastructure for the future.

The policy infrastructure is an important, but often overlooked, element in Labour’s chances of success and is equally as crucial in the U.S. In “The Making of a Movement: Who’s Shaping Corbynism?”, Christine Berry observes that any new political movement needs to have a strong intellectual infrastructure helping to generate ideas, policy proposals and political muscle to advance the project. Conservatives on both sides of the Atlantic recognized this reality long ago, but liberals and progressives have not done the same kind of institution-building. For Corbyn and Labour as well as for progressives in the U.S., such policy shops need to be stood up and staffed as quickly as possible.

Unfortunately for progressives in the U.S., the policy infrastructure is even thinner than it is in the UK, although the grassroots support for a major economic transformation is significant and growing. There are many allies doing important work in universities across the country as well as research institutions, among them the Democracy Collaborative, the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS), the Business Alliance for a Local Living Economy (BALLE) and the Institute for Local Self Reliance (ILSR). But these organizations mostly stand apart from the Democratic Party, which, itself, does not have a faction comparable to the Corbyn wing in Labour.

For the most part, the Democratic Party has not recognized the multiple perils of neo-liberalism or the opportunity to get out of its self-imposed straightjacket by going in a new direction. If it were to offer ideas such as those in the Labour Manifesto to direct major investments to stagnant urban, formerly industrial, and rural areas, it could rebuild the national economy and significantly augment its political strength at the same time.

None of this can happen quickly and there is a good case to be made that the current progressive agenda to guarantee affordable health insurance to all Americans as a right, provide free education for those who want it, and legislate a living wage is a necessary and very ambitious first step. But progressives in the U.S. also need to be thinking bigger if they are not to be stymied by conservatives and their deep pocketed allies.

For the long term, progressives should think along the same lines as the Labour Party in Britain in order to democratize the economy by empowering communities, workers and employee-owned enterprises and cooperatives, while directing investments to impoverished and stagnant regions and putting limits on the accumulation of wealth by corporations and stockholders. They should also be building political power by promoting pro-union legislation, massive funding for renewable energy, public banking and changes in corporate governance. “For the many, not the few” is a motto for progressives on this side of the Atlantic as well.