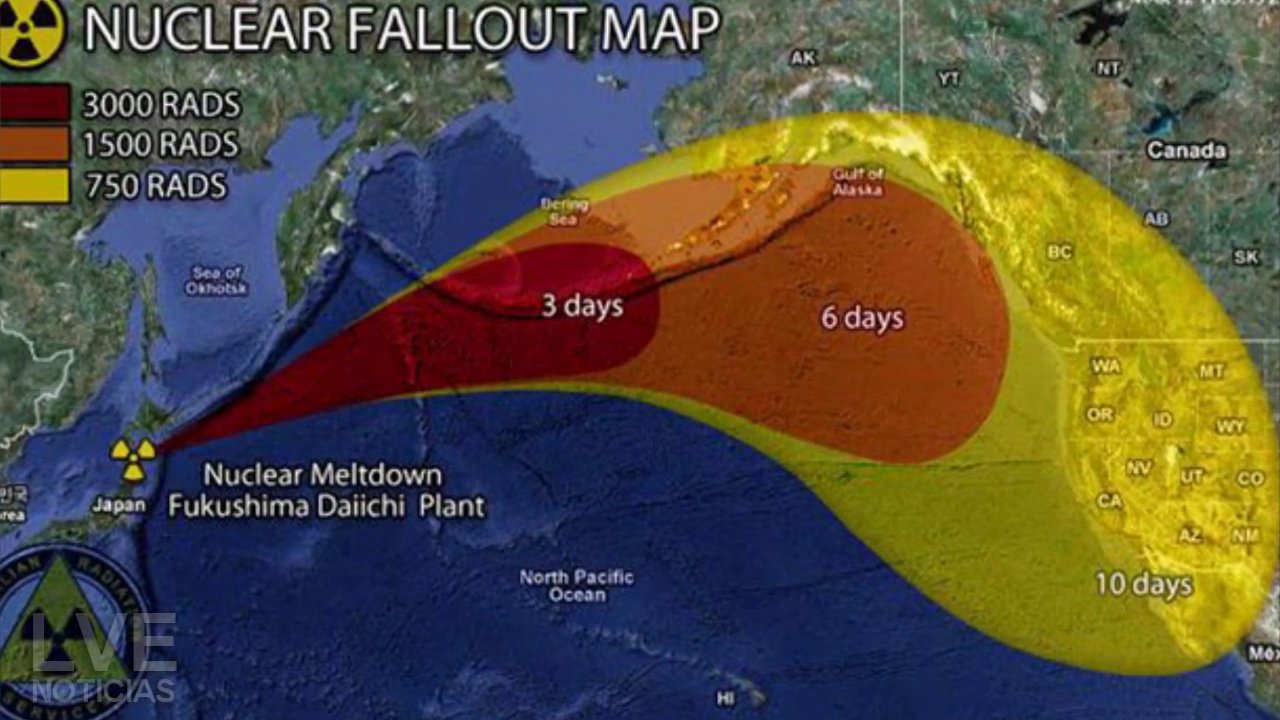

On March 11, 2011, a 9.0 magnitude earthquake off the coast of northeastern Japan triggered a tsunami that led to the meltdown of three nuclear reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant. While immediate health consequences are yet to be determined, more than 159,000 people were evicted from areas deemed too radioactive for human habitation. The World Health Organization has warned about “increased risk of certain cancers” for people in the most contaminated areas.

In the U.S. the disaster led to the creation of a federal task force and new safety and security standards at nuclear plants. On the fourth anniversary of the Fukushima disaster, Americans may be surprised to learn that no one in Japan has been held accountable. In fact, Japanese police and prosecutors have yet to conduct a thorough investigation.

The Fukushima victims are demanding criminal prosecution of the Tokyo Electric Power Co. (TEPCO) and relevant government officials for criminal negligence for not safeguarding the reactors and the often catastrophic mishandling and misinformation during and after the disaster.

The innocent people whose lives were devastated by an arguably preventable nuclear disaster believe a successful investigation and prosecution will result in more stringent regulations, more cautious and responsible corporations and ultimately the protection of future generations. All this is crucial. But a public accounting of the tragedy is just as urgent not only to Fukushima victims but also to the disenfranchised victims of radiation exposure around the world.

Seeking accountability

I feel a personal connection to the downwind victims of Fukushima. I, too, have felt disempowered and invisible, longing to see those responsible for my radiation-induced health damage to finally be brought to justice. Just as Fukushima’s children could have been protected from thyroid cancer, thousands of people, including me, were exposed to radiation discharged decades ago from the (still leaking) Hanford nuclear weapon production facility near my childhood home in Richland, Washington.

As in Richland, the children of Fukushima were not given potassium iodide tablets to block the uptake by our developing thyroid glands of radioiodine in contaminated milk and food — a simple protective measure understood since the dawn of the atomic age. Both Hanford and Fukushima communities put their trust in authorities who violated that trust and put their lives in danger.

I don’t want to see anyone else’s lives destroyed by radiation and nuclear catastrophes. A criminal investigation of Fukushima sets a precedent for governments and corporations around the world, declaring, “You are responsible for nuclear safety.”

Any nuclear disaster can have global health implications. This was demonstrated in reports of health damage across Europe after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in Ukraine in 1986 and now in suspected damage to the marine ecosystem after Fukushima Daiichi, where 300 tons of radiation-contaminated water pours into the Pacific Ocean daily.

The Japanese Nuclear Regulation Authority recently approved the restart of two nuclear reactors at the Takahama complex in Fukui prefecture on the island of Honshu’s west coast. This makes the need for accountability even more urgent. Without fear of prosecution, will continued unsafe practices contribute to new disasters?

Fukushima victims have tried for years to compel police and district prosecutors to charge TEPCO and government officials with criminal negligence. In June 2012 more than 1,000 Fukushima residents filed a complaint with the Fukushima District Prosecutor’s Office, calling for the indictment of 33 people, including the management of the Fukushima nuclear plant and relevant officials.

Their action became a national movement in Japan. In November 2012 more than 13,000 people, many of them from outside Fukushima prefecture, joined the complaint. In early 2013 supporting petitions signed by more than 100,000 people were submitted to the Fukushima District Prosecutor’s Office. Scores of rallies, lectures and press conferences were held across Japan to demand legal action.

But these protests, filings and demonstrations have not compelled Japanese prosecutors to initiate legal proceedings. The case now goes to a committee for inquest of prosecution, a group of citizens that can order a case be reinvestigated and prosecuted. If the committee finds that the case should be prosecuted, the court will designate a lawyer to conduct the duties of the public prosecutor in the case, and the designated lawyer will prosecute suspects and conduct a trial.

As of today, Japanese police and prosecutors have turned a deaf ear to these pleas. This disregard of their losses and sacrifices has deeply affected victims; some have committed suicide. Many others are redoubling their efforts to be heard. We victims know that you can have a thousand rallies in the street in vain. Without an official forum to legitimize our concerns, no change happens.

Victims Speak

To bring global attention to their cause, in April 2015, Fukushima victims will publish an English translation of select statements from their complaint as a book, available to the English-speaking world, “Will You Still Say No Crime Was Committed?” Their goal, according to Ruiko Muto, the chairwoman of the Complainants for Criminal Prosecution of the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster, is to let the world “know that the Fukushima nuclear disaster has not been brought under control, that it continues to spread harm and that the nation of Japan is choosing to abandon the victims.”

The book’s personal stories are compelling. Their statements offer a rare glimpse into their deep sense of betrayal. They tell of mortgages still being paid on contaminated homes that they can never inhabit. Livelihoods have been lost, families torn apart. They are under constant stress, uncertain whether the food they are eating or the air that they breathe is poisoned, unable to trust the authorities to tell them the truth.

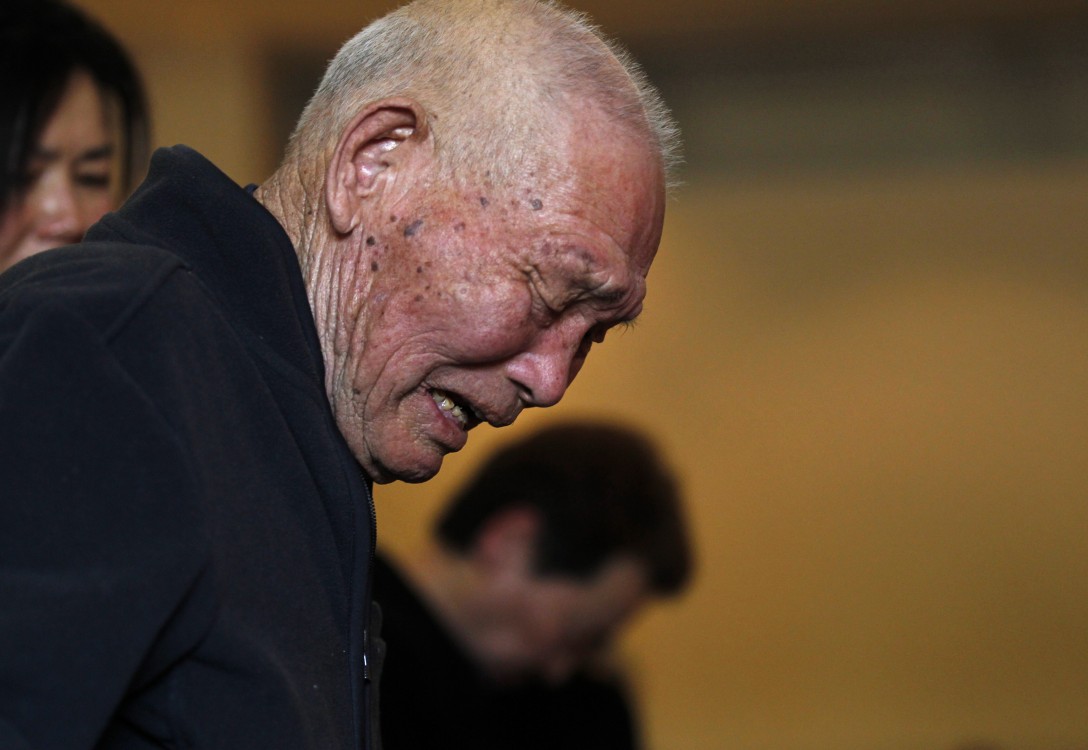

“With no one taking responsibility for the nuclear accident, what we have is a situation of paradise for the perpetrators, hell for the victims. I cannot go to my grave like this,” says complainant No. 48, age 68.

Through the English-language publication of their stories, grief-stricken Fukushima victims are now asking the English-speaking world to join in their battle for justice. These innocent victims of Fukushima Daiichi have reached across the Pacific to raise awareness and obtain our help.

Let’s add our voices to theirs.

Trisha Pritikin is a Hanford Downwinder, an attorney and an internationally recognized advocate on behalf of populations exposed to Hanford’s radiation releases. She blogs at www.trishapritikin.com.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments