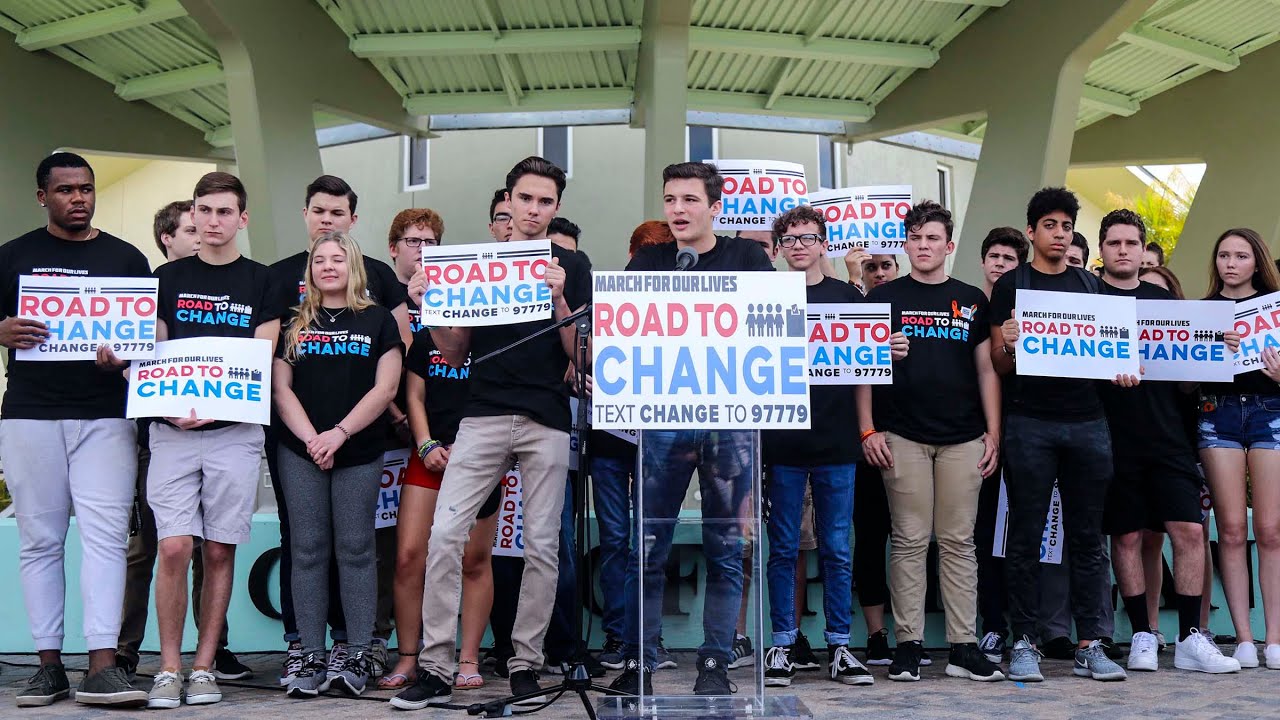

Beginning in June, student activists from Parkland, Florida, have traveled across the country on their Road to Change campaign. The initiative seeks to inform young people about gun laws and encourage them to vote this fall for politicians who support gun reform and pledge to take no donations from the National Rifle Association (NRA). Most town hall discussions have brought in large crowds. Every session has included several students from Parkland, local high school students from the respective area, and youth from Chicago whom activists met prior to launching the tour.

On the surface, the activists will have to overcome long odds. Young people have historically come out in low number for elections. The number is staggeringly low for midterms. A recent poll from the Public Religion Research Institute and the Atlantic revealed that only 28 percent of young adults report that they are “absolutely certain” they will vote in midterms. This reality makes the Parkland activists’ efforts look bleak. However, youth political organizing during the summertime have produced tremendous results in the past.

From Mississippi to New York City, Indianapolis and beyond, young people have always taken advantage of the liberty they enjoyed during summers, particularly those who came from affluent families in urban and suburban areas and had more recreational time than their peers of lower socioeconomic status and rural counterparts. The Parkland students are embarking on a similar path as the 1964 Freedom Summers, in which civil rights activists and northern white volunteers registered black residents in Mississippi to vote amidst threats of violence.

Jaclyn Corin, one of the Parkland activists, has called the campaign "unprecedented". The popular phrase underscores how youth activists have long used their summer freedom to make significant changes in society and in their local communities. Youth in other cities are currently using this time to organize their peers in cities like Detroit, Philadelphia and many other locations around the country.

Accounts of organizing efforts by high school-aged youth have not been well publicized, in contrast to their collegiate counterparts. But high schoolers have been just as effective. High school students have been able to create citywide underground newspapers and youth-led political organizations as well as organized conferences on a city- and statewide basis.

In 1968 in New York City, students formed the New York High School Student Union in the midst of a teacher strike that lasted from May to November. Students did not start school until the strike ended. Not only did the students create an organization that mobilized for collective action. They also published an underground newspaper that had a circulation of up to 40,000 copies a month. This occurred at a time when young people lacked modern-day technology, printed publications on mimeograph machines and distributed papers through the mail or on the street.

Organizing in the summer even occurred in places that were quite placid. For example, Indianapolis, Indiana, had no coherent political movement led by high school students prior to 1971. However, a group of young activists used their free time during the summer to visit concerts, public parks and festivals where they formed contacts with their peers across the city. What resulted from these organizing activities was the city’s first underground high school newspaper, called the Corn Cob Curtain, which allowed the activists to build a radical political consciousness among city youth for two years. School administrators banned the publication and the conflict sparked a legal controversy that went all the way up to the Supreme Court in 1975.

The two biggest differences between contemporary youth activists and their 1960s counterparts are technology and inclusiveness, as demonstrated by the youth-led gun reform movement. In an era of social media, Parkland activists mobilized students nationwide within the span of a month and organized subsequent protests. Technology also has allowed them to quickly plan the Road to Change by setting up a text messaging system to inform followers about current activities.

Additionally, Parkland students have forged a dialogue about gun control beyond placid suburban communities. They’ve done this by visiting communities plagued by gun violence, addressing the lack of media coverage of black students, and demanding that Americans address gun reform in many shapes and sizes. Community turn-out at town halls have brought in diverse crowds. Despite the fact that the movement began with activists from affluent households – the average household income in Parkland, Florida, is over $128,000, according to the U.S. Census – the movement has featured students from all socio-economic backgrounds.

The results of the Road for Change and other movements burgeoning across the country this summer have yet to be seen. Young people could come out in record numbers to vote this fall, or the percentage could remain stagnant or even drop. Whatever results, the Parkland activists have had a profound impact on youth across America who have been galvanized to make change happen in their communities.