Cynthia Ennis does not have fond memories of the last time the government shut down, in the winter of 1995.

Ennis worked in the Social Security Administration in Baltimore, Md., at the time, and remembers the acute anxiety of not knowing when she was going to get her next paycheck. The budget impasse between President Clinton and congressional Republicans then shuttered the government twice — first for six days and then for sixteen, through the holidays.

"It’s horrifying," Ennis said. "The gas and electric company, your mortgage company, they're not going to want to understand or want to hear about a furlough. They want payment of their money."

Ennis was lucky, she was deemed an "essential" employee and kept coming to work, but did not collect her salary until Congress voted later to back-pay federal workers.

Retired now and president of a local union representing Social Security and Centers of Medicaid and Medicare workers, Ennis is outraged that the government might shutter again, leaving 800,000 "not excepted" government employees furloughed.

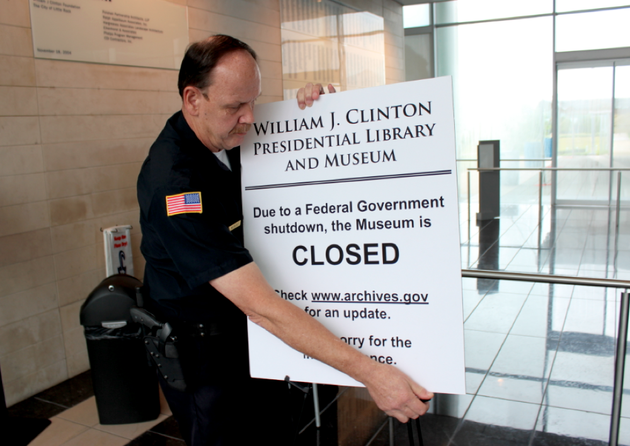

Washington and federal agencies around the country are bracing for a probable shutdown, with the Office of Management and Budget and the U.S. Office of Personnel Management issuing guidelines about who can keep coming to work and who has to stay at home without pay until there’s a resolution.

Negotiations between Republican and Democratic lawmakers are at a standstill over how to fund the government through the fiscal year, starting October 1. GOP lawmakers in the House insist that the Senate and President Obama agree to delay or defund the Affordable Care Act as a condition for funding the rest of the government, while Democrats insist on a clean, no-strings temporary spending bill—known as a continuing resolution.

In shutdowns past, the terms "essential" and "nonessential" were used to make the distinction between the two groups of workers. Now, the classifications have changed to "excepted" and "not excepted," with excepted workers identified as those "who are performing emergency work involving the safety of human life or the protection of property," among other functions.

But that serves as little comfort to workers who are being told that their jobs might be on hiatus for an indeterminate period of time.

"They're all disgusting terms—essential and nonessential, excepted and not excepted. Because the bottom line you need everybody here at work and Congress is to me not excepted, with the political games they’re playing with people’s lives," Ennis said.

The decision is ultimately left up to individual agencies themselves, which makes for some peculiarities. According to the New York Times, military recruiters in the Department of Defense will come to work, but environmental engineers will not. Food inspectors with the Department of Health and Human Services and labor statisticians with the Census Bureau are furloughed, but National Weather Service meteorologists and drug-enforcement agents will have to report for duty.

"It's very offensive," said Colleen Kelley, the president of the National Treasury Employees Union. "Federal employees know the work they do every day matters and it needs to be done."

Jessica Klement, the legislative director of the National Active and Retired Federal Employees Association, said government workers are an easy target for elected officials, who in decrying Washington’s bloated bureaucracy find it easy to beat up on civil servants. In actuality, the men and women who staff dozens of agencies and perform a variety of public functions have already been under a three-year salary freeze. Some have already taken furlough and worked without pay because of sequestration.

"Who else has been asked to give money and take a hit on their paychecks to help our country’s financial situation?" Klement said. "There’s just a lot of misconceptions about who federal employees are and what their benefits are and Congress members feed into that mentality."

Ron Angel, who is an employee of the U.S. Forest Service in Sandpoint, Idaho, said there’s a lot of stress and anxiety coming from other workers. Some of the firefighters who are routinely dispatched to battle wildfires are going to be furloughed, a stinging rebuke for men and women who put their lives in danger for the public interest.

Angel himself worked as a firefighter for more than 30 years, before he injured his back for the third time. Now a full-time union representative, his agency has not yet made a determination about who is "essential" and he does not know if he will be coming into work after tomorrow.

"It’s not good for morale. Of course everybody thinks that their job is the most important in the world so when you’re told otherwise, you’re think ‘Really? How about the rest of the time?’" Angel said.

"The military is going to keep getting paid," he added, referring to active-duty personnel. "But our people are dying every year too. It’s got a lot of people really upset."

Michael Ottinger, an employee of the Environmental Protection Agency in Cincinnati, Ohio, is not interested in assigning blame. He just wants Congress to think of the consequences a shutdown would have in people’s lives.

"These people are not rich people and they’re not political appointees and whether it’s intentional or unintentional we are being squeezed badly by the circumstances here," he said.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments