I and my fellow plaintiffs have begun the third and final round of our battle to get the courts to strike down a section of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) that permits the military to seize U.S. citizens, strip them of due process and hold them indefinitely in military facilities. Carl Mayer and Bruce Afran, the lawyers who with me in January 2012 brought a lawsuit against President Barack Obama (Hedges v. Obama), are about to file papers asking the U.S. Supreme Court to hear our appeal of a 2013 ruling on the act’s Section 1021.

“First the terrorism-industrial complex assured Americans that they were only spying on foreigners, not U.S. citizens,” Mayer said to me recently. “Then they assured us that they were only spying on phone calls, not electronic communications. Then they assured us that they were not spying on American journalists. And now both [major political] parties and the Obama administration have assured us that they will not detain journalists, citizens and activists. Well, they detained journalist Chris Hedges without a lawyer, they detained journalist Laura Poitras without due process and if allowed to stand this law will permit the military to target activists, journalists and citizens in an unprecedented assault on freedom in America.”

Last year we won round one: U.S. District Judge Katherine B. Forrest of the Southern District of New York declared Section 1021 unconstitutional. The Obama administration immediately appealed her ruling and asked a higher court to put the law back into effect until Obama’s petition was heard. The appellate court agreed. The law went back on the books. I suspect it went back on the books because the administration is already using it, most likely holding U.S. citizens who are dual nationals in black sites in Afghanistan and the Middle East. If Judge Forrest’s ruling were allowed to stand, the administration, if it is indeed holding U.S. citizens in military detention centers, would be in contempt of court.

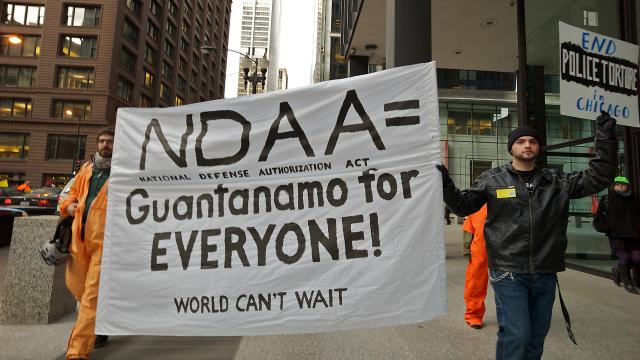

In July 2013 the appellate court, in round two, overturned Forrest’s ruling. All we have left is the Supreme Court, which may not take the case. If the Supreme Court does not take our case, the law will remain in place unless Congress strikes it down, something that federal legislators have so far refused to consider. The three branches of government may want to retain the ability to use the military to maintain control if widespread civil unrest should occur in the United States. I suspect the corporate state knows that amid the mounting effects of climate change and economic decline the military may be all that is left between the elite and an enraged population. And I suspect the corporate masters do not trust the police to protect them.

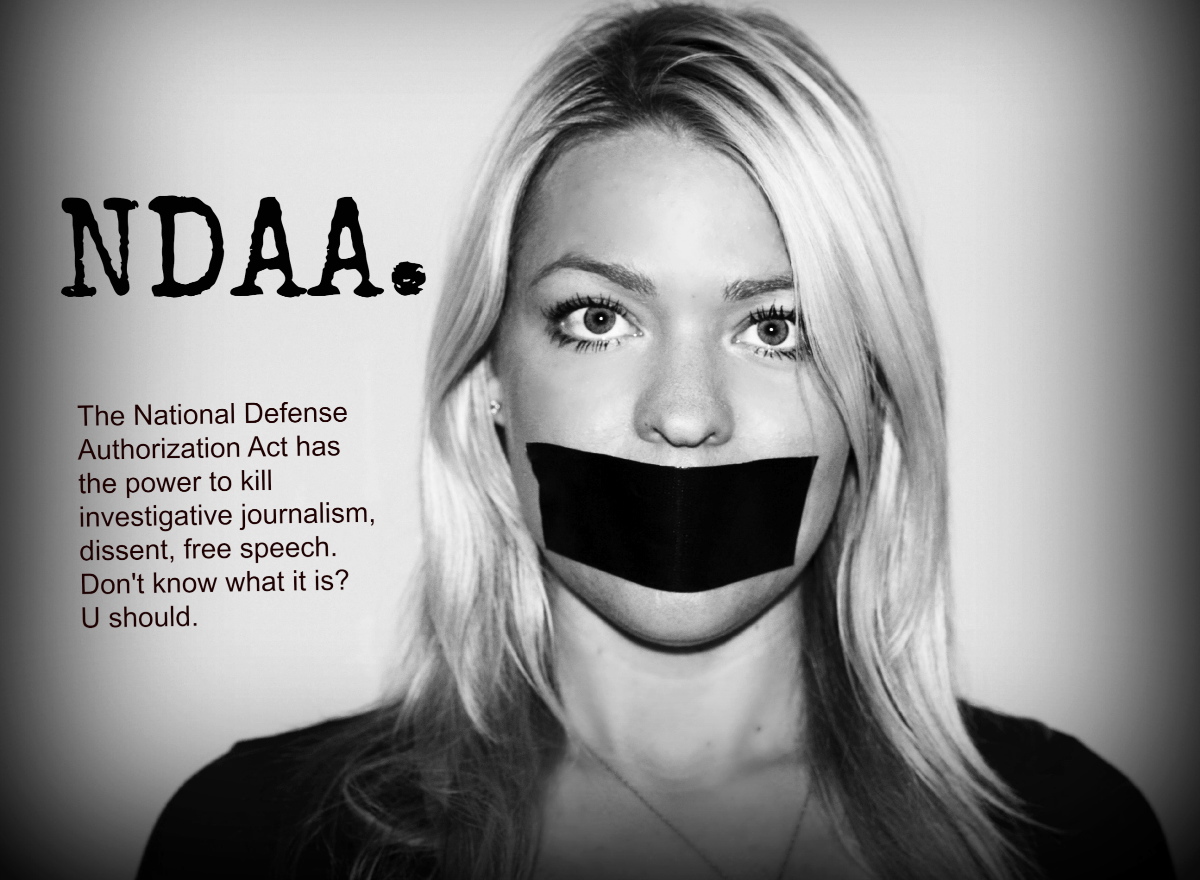

If Section 1021 stands it will mean that more than 150 years of case law in which the Supreme Court repeatedly held the military has no jurisdiction over civilians will be abolished. It will mean citizens who are charged by the government with “substantially supporting” al-Qaida, the Taliban or the nebulous category of “associated forces” will be lawfully subject to extraordinary rendition. It will mean citizens seized by the military will languish in military jails indefinitely, or in the language of Section 1021 until “the end of hostilities”—in an age of permanent war, for the rest of their lives.

It will mean, in short, obliteration of our last remaining legal protections, especially now that we have lost the right to privacy, and the ascent of a crude, militarized state that serves the leviathan of corporate totalitarianism. It will mean, as Forrest pointed out in her 112-page opinion, that whole categories of Americans—and here you can assume dissidents and activists—will be subject to seizure by the military and indefinite and secret detention.

“As Justice [Robert] Jackson said in his dissent in the Korematsu case, involving the indiscriminate detention of Japanese-American citizens during World War II, once an unconstitutional military power is sanctioned by the courts it ‘lies about like a loaded weapon, ready for the hand of any authority,’ ” Mayer said.

In our lawsuit the appellate court never directly addressed the issue of using the military to hold citizens and strip them of due process—something that is clearly unconstitutional. Instead, the court held that I and the other plaintiffs did not have standing to bring the case. It said that because none of us had been imminently threatened with arrest we had no credible fear. This was an odd argument. When I was a New York Times reporter I was, as stated in court, arrested and held by the U.S. military in violation of my First Amendment rights as I was covering conflicts in the Middle East. In addition I was briefly detained, without explanation, in the Newark, N.J., airport by Homeland Security as I returned from Italy, the court was told.

During the five years I covered the war in El Salvador the Reagan administration regularly denounced reporters who exposed atrocities by the Salvadoran military as “fifth columnists” for the rebel movement, a charge that made us in the eyes of Reagan officials at the very least accomplices to terrorism. This, too, was raised in court, as was the fact that during my seven years as a reporter in the Middle East I met regularly with individuals and groups, including al-Qaida, that were considered terrorists by the U.S. government. There were times in my 20-year career as a foreign correspondent, especially when I reported events or opinions that challenged the official narrative, that the U.S. government made little distinction between me and groups that were antagonistic to the United States. In those days there was no law that could be used to seize and detain me. Now there is.

Journalist Alexa O’Brien, who joined the lawsuit as a plaintiff along with Noam Chomsky, Daniel Ellsberg and others, was incorrectly linked by the security and surveillance state to terrorist groups in the Middle East. O’Brien, who doggedly covered the trial of Chelsea (formerly Bradley) Manning, co-founded US Day of Rage, an organization dedicated to electoral reform. When WikiLeaks in February 2012 released 5 million emails from Stratfor, a private security firm that does work for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the Marine Corps and the Defense Intelligence Agency, it was revealed that the company was attempting to tie O’Brien and her organization to Islamic radicals and websites as well as jihadist ideology.

Fred Burton, Stratfor’s vice president for counterterrorism and corporate security and a former deputy director of the counterterrorism division of the State Department’s Diplomatic Security Service, and Thomas Kopecky, director of operations at Investigative Research Consultants Inc. and Fortis Protective Services LLC, had an email exchange over this issue. Kopecky wrote: “I was looking into that US Day of Rage movement and specifically asked to connect it to any Saudi or other fundamentalist Islamic movements. Thus far, I have only hear[d] rumors but not gotten any substantial connection. Do you guys know much about this other than its US Domestic fiscal ideals?” Burton replied: “No, we’re not aware of any concrete connections between fundamentalist Islamist movements and the Day of Rage, or the October 2011 movement at this point.” But that soon changed. Stratfor, through others working in conjunction with the FBI, falsely linked US Day of Rage to al-Qaida and other Islamic terrorist organizations. Homeland Security later placed her group on a terrorism watch list.

This will be the standard tactic. Laws passed in the so-called war on terror will be used to turn all dissidents and activists into terrorism suspects, subjecting them to draconian forms of state repression and control. The same tactic was used during the anti-communist hysteria of the 20th century to destroy union leaders, writers, civil rights activists, intellectuals, artists, teachers, politicians and organizations that challenged entrenched corporate power.

“After 12 years of an undeclared permanent war against an undefined enemy and multiple revelations about massive unconstitutional spying by the government, we certainly hope that the Supreme Court will strike down a law that replaces our civilian system of justice with a military one,” said Mayer. “Unless this happens there will be little left of judicial review during wartime.”

Afran, a law professor at Rutgers University, asked last week during a conversation with me: “Does the Army have to be knocking on your door saying, ‘Come with me,’ before there will be the ability to challenge such a law?” He said the appellate court’s ruling “means you have to be incarcerated before you can challenge the law under which you’re incarcerated.”

“There’s nothing that’s built into this NDAA [the National Defense Authorization Act] that even gives a detained person the right to get to an attorney,” Afran said. “In fact, the whole notion is that it’s secret. It’s outside of any judicial process. You’re not even subject to a military trial. You can be moved to other jurisdictions under the law. It’s the antithesis of due process.”

The judges on the appellate court admitted that we as plaintiffs had raised “difficult questions.”

“This is a way of acknowledging they’re troubled by the apparent lack of constitutionality of the law,” Afran said during our conversation. “But they were not willing to face the question head on. So, in effect, they said, ‘Well, when someone’s threatened with arrest, then we have a concrete injury.’ But no one’s going to be threatened with arrest. They’ll simply be arrested. They’re not going to send a letter saying, ‘By the way, on Thursday next we’re going to place you in military custody.’ … The whole point of the law is that they’re going to come in and take you [in secrecy].”

The appellate court stated that the law does not apply to U.S. citizens and permanent residents. In reading the law this way the justices were saying, in effect, that I and the other plaintiffs had nothing to fear. Afran called this a “circular argument.” The court, in essence, said that because it did not construe the law as applying to U.S. citizens and lawful residents we could not bring the case to court.

“They seem to accept a lot of what we said, namely that the whole history of the jurisprudence, of the court decisions, is that American civilians cannot be placed in military custody,” Afran said. “And they accept the idea that Section E of the statute says, ‘Nothing herein shall be construed to affect existing authorities as to the detention of U.S. citizens.’ So on the basis of that they say this is not meant to add any new powers to the government and since the government doesn’t have power over civilians in this way the law can’t be extended to civilians. The problem is by saying there’s no standing, they deprive the district court of entering an order, saying and declaring that the statue does not apply to U.S. citizens or permanent residents, lawful residents in the U.S.”

The court, in essence, accepted the principle that citizens cannot be taken into military custody but refused to issue a direct order saying so that would be enforceable.

“We have the absurdity of the court of appeals, one of the highest courts in the country, saying this law cannot touch citizens and lawful residents, but depriving the trial court of the ability to enter an order blocking it from being used in that way,” Afran said. “The lack of an order enables future [military] detentions. A person may have to languish for months, maybe years, before getting a court hearing. The [appellate] court correctly stated what the law is, but it deprived the trial court of the ability to enter an order stopping this [new] law from being used.”

“A law is not constitutional just because habeas corpus says you have a right to go to court to try to get out,” Afran said in speaking about the legal mechanism by which someone might challenge custody. “The citizen is entitled not to be detained in the first place absent probable cause. Habeas corpus is a remedy of last resort. It’s not there to justify the use of unconstitutional detention laws.”

The Supreme Court takes between 80 and 100 cases a year from about 8,000 requests. There is no guarantee our appeal will ever be heard. If we fail, if this law stands, if in the years ahead the military starts to randomly seize and disappear people, if dissidents and activists become subject to indefinite and secret detention in military gulags, we will at least be able to look back on this moment and know we fought back.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments