In a fluorescent-lit hearing room in Oakland, California, this week, gathered around a crescent-moon table in front of two dozen onlookers, a group of local politicians was locking horns over a question that has baffled this city for more than a year: What's the best way to punish Goldman Sachs?

“I am not a fan of Goldman Sachs,” councilmember Pat Kernighan said. “They are a very greedy business that operates without regard to anything other than their bottom lines. But I am frustrated with the amount of time and effort being put into this.”

The “this” councilmember Kernighan spoke of is the city of Oakland’s long-running feud with Goldman. It’s a scrappy fight that dates back fifteen years, involves millions of dollars and a soured bond deal, and has galvanized activist groups and ordinary citizens in opposition to what many of them feel is a glaring example of financial corruption hurting a struggling city. And it has resulted in one of the odder situations in American municipal politics — namely, one in which a midsize city is trying to run Wall Street’s most powerful investment bank out of town, but can't quite figure out how.

The trouble started in 1998, when the city of Oakland entered into an interest-rate swap with Goldman. Under the terms of the swap, Oakland exchanged $187 million in floating-rate bonds for bonds with a fixed interest rate of 5.7 percent, in order to hedge against the possibility that interest rates would rise to 8 or 9 percent. But when rates fell to nearly zero instead, Oakland was stuck paying an above-market interest rate on its debt, at a cost of roughly $4 million a year, at a time when the city’s finances were in shambles.

In some ways, Oakland's problems are a reflection of the fights between lenders and municipalities taking place all over the country, as cities try to recover from a recession that created crippling budget shortfalls and delayed infrastructure projects. Budget problems are especially bad in California, where one city — Stockton, an hour to the east — became the largest U.S. city to go bankrupt earlier this month. Oakland faces a deficit of between $19 million and $26 million for fiscal year 2013, and shortfalls in previous years have resulted in layoffs and furloughs of public employees.

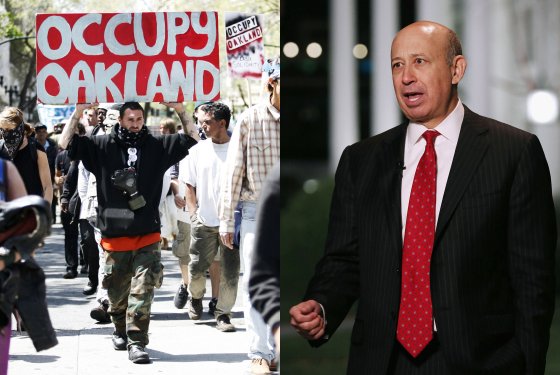

Oakland's interest rate swap, which expires in the year 2021, was a classic wrong-way bet, and a less proud municipality might have sucked it up and moved on. But Oakland decided it wanted out. Last year, city leaders and activists led protests outside Goldman’s San Francisco offices, and harangued Goldman CEO Lloyd Blankfein at the firm’s annual shareholder meeting, asking Goldman to unwind the swap deal without charging Oakland the $16 million termination fee specified in its contract. The city's position was, essentially: You guys got bailed out of your bad investment decisions. Why can't we, too?

But Goldman refused to back down. "That's not how the financial system could work," Blankfein said last year, in response to an Oakland representative's plea for a get-out-of-swap-free card. "Were we to [cancel the swap at no cost] ... we would be frankly paring the interests of our shareholders and the operations of the company. I don't think it's a fair thing to ask."

So, in December, after an eight-hour deliberation, the city council voted to go ahead with a so-called debarment process, which would involve an investigation, a hearing, and an eventual decision that could ban the bank from doing business with the city for up to five years. But the effort got stuck in the mud. For months, councilmembers have been quarreling with the city administrator's office, which is in control of the debarment process, and at least one has accused it of dragging its feet on purpose.

On Tuesday, the Oakland city council's finance and budget committee met to hear a progress report on the debarment process. The news wasn’t good: A representative for the city administrator told the council members that a full investigation by a hired outsider would take a minimum of three months, followed by another several months to weigh the evidence and conduct a hearing. And some city council members are getting sick of waiting.

“We’ve spent a year talking about this,” councilmember Libby Schaaf said. “It feels like this is taking a lot of staff resources.”

"We need to move the agenda," concurred councilmember Desley Brooks.

Among the questions dividing the committee is whether it's worth going after Goldman at all. Some members say yes, arguing that large financial institutions have taken advantage of cities around the country with complicated rate-swap deals that leave them on the hook for large payments for too long. These people argue that since Goldman and other banks enjoyed the privilege of massive federal bailouts during the financial crisis, they should pay the gift forward to cities around the country.

"The problem is much bigger than Oakland," said councilmember Rebecca Kaplan at Tuesday's hearing. "There still hasn't yet been an adequate response at the federal level, and I am proud for Oakland to be in the lead on that. It's important for us to continue to send a message."

Other members, like Kernighan, expressed that while banning Goldman would be a meaningful symbolic gesture, it wouldn't necessarily accomplish much. There have been no lawsuits filed alleging fraud or misrepresentation of the swap's terms, and few people are claiming that it's Goldman's fault that interest rates have gone down. (The ones who are generally use a roundabout argument that involves Goldman's lobbying efforts and the Federal Reserve's quantitative easing program.) And even some councilmembers are willing to admit that Goldman has no duty — legal or otherwise — to tear up the deal, simply because it ended up going poorly for Oakland.

"The swap deal the city entered into ... is a legal, enforceable contract," Kernighan said. "It is a bad deal, but it’s a deal that the city went into with its eyes open. As much as I would like to get out of it, I don’t think we have the legal grounds."

Goldman, which declined to comment for this story, has made some concessions to Oakland, by offering to renegotiate the swap deal in a way that would save Oakland a few hundred thousand dollars. But an independent review last year found that the swap deal, despite its problems, had actually saved Oakland $37.5 million compared to what a comparable floating-rate deal would have cost. And Oakland represents a statistically insignificant part of Goldman's clientele, meaning that while being kicked out of Oakland might create embarrassment for the firm, it's not likely to damage it financially.

Goldman has found some unlikely supporters in Oakland — like Joe Keffer, a local SEIU representative, who spoke at Wednesday's hearing and urged the committee to drop the debarment process to focus on other matters.

"There is already a resolution," Keffer said, referring to city council's December vote to authorize the city administrator to go ahead with the debarment process. "We will have made between $4 million and $6 million more in payments to Goldman Sachs by the time we get to debarment."

Councilmember Schaaf, who at one point urged her colleagues to "Google Rolling Stone" to find a comprehensive public record of Goldman's crisis-era misdeeds, nevertheless opposed kicking Goldman out of town without sufficient evidence that it was in the wrong. ("We gambled. We lost. That happens all the time, and we have to be grown up about it.") She also pointed out that Oakland is currently in litigation with roughly twenty other financial institutions over matters like Libor, the interest-rate benchmark that was allegedly manipulated by a coterie of global banks. If Oakland is barring Goldman from doing business with the city because of dealings it doesn't like, Schaaf wondered, why not those other firms, too?

In the end, the committee passed the debarment issue up to the full city council, keeping the process of kicking Goldman out of town on track for an eventual resolution. But it did so with a spirit of resigned admission that even though Oakland is probably not going to get its money back, it's still worth putting Blankfein and his band of bankers in their place.

"I frankly don’t think they are ever going to let us out" of the swap deal, said Kernighan. "But we can make them uncomfortable."

Originally published by New York Magazine.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments