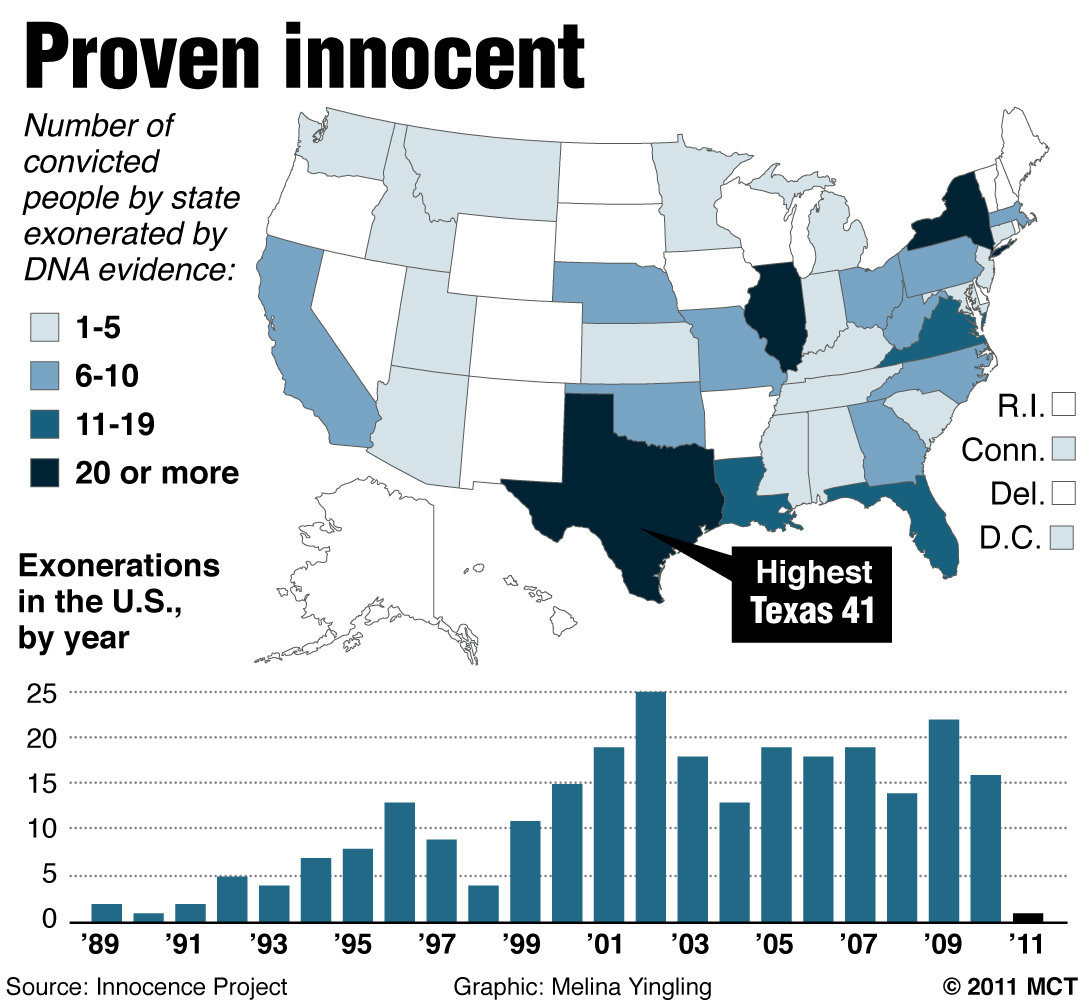

“False confessions are one of the most counter intuitive aspects of human behavior,” says Saul Kassin, a leading expert in the study of false confessions and a Distinguished Professor of Psychology at John Jay College. According to Kassin, false confessions are a contributing factor in more than 25% of the 311 DNA exoneration cases in the United States.

Professor Kassin’s research helps demystify why people confess to crimes that they did not commit. The term, false confession, is actually a misnomer. A confession is a rational decision by someone who chooses to accept responsibility for his or her actions when the guilt of the crime becomes too much to bear.

A false confession is something completely different. When someone falsely confesses, it’s not a one-way conversation and it doesn’t take place during an interview with the police. Rather, it occurs during an interrogation — a totally different type of interaction.

It is a largely unknown fact that police are allowed to present false information to extract a confession. Hence, the interrogation process can be disorienting and can cause people to doubt themselves. Also, in an interrogation, the person questioned is considered a suspect — someone who the police already think is guilty.

The problem is that the police can be wrong.

In his November 12, 2012, review of “The Central Park Five,” Los Angeles Times film critic Kenneth Turan said the film “serves as a cinematic primer on what has become one of the most disturbing aspects of our criminal justice system: the ability — and the unabashed willingness — of police to psychologically manipulate people into confessing to things they have not done.”

Raymond Santana, who is among the Central Park Five, falsely confessed. Santana recounted in a video for Be the Witness—a campaign launched by The Innocence Project, which helps exonerate wrongfully convicted individuals based on DNA testing—that the officers who interrogated him were friendly at first. But when they didn’t receive the information they wanted, they became aggressive, yelling in his ear. He was 14 years old at the time.

Of the Central Park Five, Kassin says, “The kids were interrogated for 14 to 30 hours, the detectives trying to break [them] down into a state of despair, into a state of helplessness, so that . . . [they were] worn down and looking for a way out." Kassin emphasizes that people who falsely confess nearly always believe that once they are away from the police, the situation can be fixed.

In another case, Jeff Deskovic was wrongly convicted of the murder and rape of a classmate, Angela Correa. Deskovic became a suspect because he was late to school the day of the victim’s murder and because he appeared overly distraught at her wake. For two months, he denied having anything to do with Correa’s death. Finally, in late January 1990, he agreed to a polygraph test, which preceded the interrogation that led to his confession.

He was held in a small room with no lawyer or parent present. Deskovic’s confession came after six hours, three polygraph sessions and intense questioning by detectives. Like most of the public — and certainly most teenagers — Deskovic did not know that the police are allowed to lie during the interrogation. The 17-year-old told the police what they wanted to hear, believing his statements would later be fixed.

“I thought it was all going to be O.K. in the end,” said Deskovic, because he was sure that the DNA testing would show his innocence.

In convicting him, the jury chose to give more weight to his tearful confession than to the DNA and other scientific evidence that excluded him from the crime. Kassin says that once a confession is made, everything changes — and it almost doesn't matter what exculpatory evidence emerges, including DNA, after the confession.

“The confession trumps all other evidence. It has to power to change eyewitness identification testimony," Kassin adds. "Forensic scientists no longer believe their own work and people who provided alibis doubt themselves.”

Among the most egregious cases of false confession, George Allen of Missouri was wrongly convicted of a murder that took place in 1982 and spent more than 30 years in prison. The crime took place during one of the heaviest snowstorms in St. Louis history.

Allen, who has schizophrenia, had been admitted to psychiatric wards several times. A month after the crime, police officers mistook him for the suspect they were looking for and picked him up. Though they recognized their mistake, police interrogated Allen and an officer prompted him to give answers to fit the crime. He was charged with murder on the basis of the false confession, convicted and sentenced to life.

Allen was freed on bond in November of 2012 when a judge vacated his conviction, ruling that police had failed to disclose exculpatory evidence. Allen was fully exonerated in January of this year and reunited with his 80-year-old mother, Lonzetta.

It is understood that police are under enormous pressure to solve violent crimes. However, it does not advance justice or public safety for an innocent person to go to prison and a guilty party to go free. For this reason, interrogations must be recorded from beginning to end to prevent false confessions and end this tragic flaw in our criminal justice system.

Audrey Levitin is Director of Development and External Affairs at The Innocence Project. Learn more about the Be the Witness campaignand about the non-profit's efforts to exonerate wrongfully convicted individuals here.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments