With Christine Blasey Ford set to appear Thursday before the Senate Judiciary Committee to testify against her attacker, Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh, and at least two more allegations of sexual assault emerging in recent days to further stain his nomination, what happens next in Washington is anyone's guess.

What isn't up for dispute is the long-term impact that these kinds of incidents of sexual assault have on the victims. Ford likely never intended for her now-famous letter, sent over the summer to the offices of California Sen. Dianne Feinstein, to go public. Over the past week she has grappled with the pressure to testify before a national audience and bring her attacker to justice.

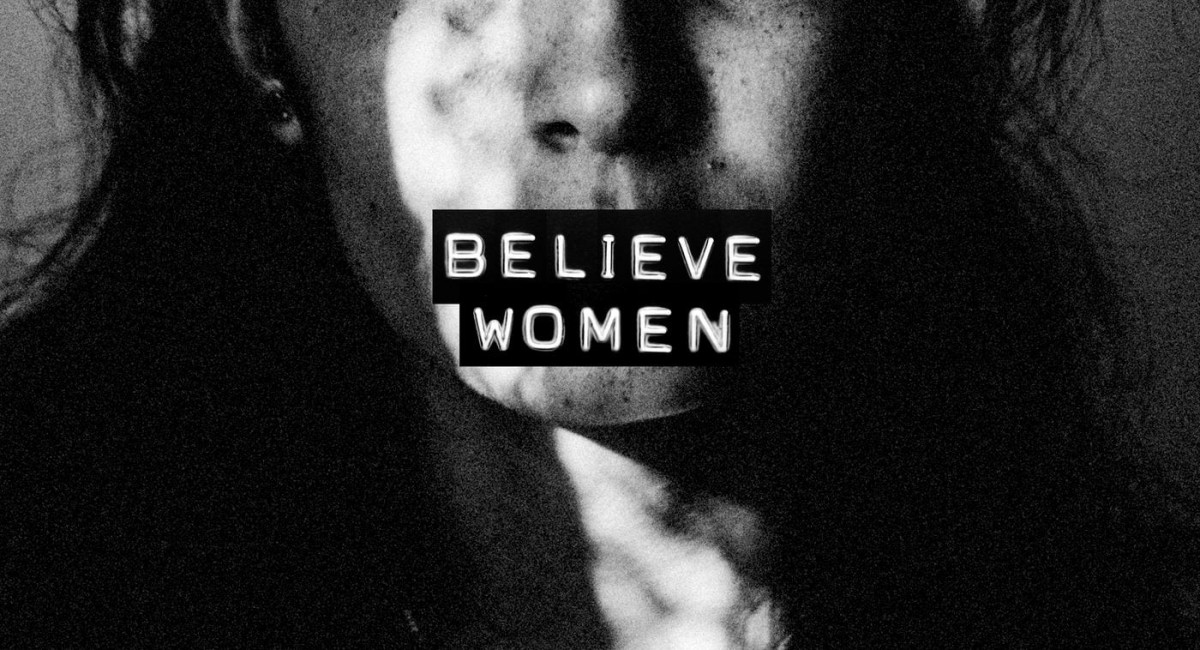

Now, her strength and courage is helping others to come forward and be heard. The fact remains that one in every six American women has been a victim of attempted or completed rape – and that doesn't include the vast numbers women who fail to report the crime. Which begs the question, in the #MeToo era: Why does it remain so difficult for women to go public with their stories of sexual assault.

According to three women at New York University, all of whom have suffered sexual assaults, the reasons vary. I asked these women to share their views and their experience living with the trauma.

Ellie

“I just remember being terrified. I knew I was about to get raped and nothing I could do was going to stop that,” recalled Ellie (not her real name), 20, who was assaulted as a senior in high school.

Ellie's attacker had been her friend since freshman year. A study by RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network), the nation's largest anti-sexual violence organization, reported that seven out of 10 victims, like Ellie, know their perpetrator.

After finding a way to escape her attacker, Ellie was embarrassed and felt she had done something wrong to cause the assault. “Maybe if I hadn’t drunk so much or kissed him or worn that dress it wouldn’t have happened,” she said.

Now, all she feels is anger.

“Something that has had such a significant impact on my life and on who I am probably didn’t affect him at all,” she added. Readers of stories like these often wonder: Why did the attacker get off the hook? In Ellie's case, after finally mustering the courage to tell her best friend about the attempted rape, her friend blamed the incident on her.

“I hated myself when that was the way she responded, but now, after finally realizing it’s not my fault, I feel more removed from the situation.”

Desiré

Desiré Garza shared a similar story of a friend in high school who disregarded her pleas and screams of pain and used the phrase, “No, you want to,” to get what he wanted from her.

“He had turned me around so that I was on my stomach and [he] held me down as he continued from behind. I kept trying to ask him to stop but he just continued to disregard everything I had been saying,” Garza said. “I was drunk, being held down, and was frozen with fear. I didn’t know what else to do except lay there, take it, and wait for it to be over.”

The next day, Garza's attacker denied her accusations and again stated that she had wanted it. Garza refrained from telling the authorities because she knew didn’t want to ruin her "friend's" life. “Everyone loved him. I couldn’t do that to him and I couldn’t do that to his family. I could only imagine how his mother would feel,” she admitted.

Mairead

Only one of the three victims I interviewed for this article, Mairead McConnell, received partial justice.

In 2015, McConnell was looking for a fun night out, but when her girlfriend started to feel sick, an NYU junior invited the two to his apartment and she agreed, thinking she could trust him.

The man left her friend alone in the bathroom while he proceeded to exploit her intoxication to seduce her. After drinking the wine he offered, she blacked out and awoke to him having sex with her on the couch. He ignored her cries and continued the assault, then got dressed and left her lying in his living room.

McConnell refused to come forward about the attack until one of her friends, along with the university public safety division, enlisted the help of the New York Police Department. In the end, the perpetrator wasn't prosecuted because reportedly "being intoxicated didn’t mean having a lack of consent,” recalled McConnell.

But after relentlessly pursuing a Title IX case through NYU, McConnell received justice when the attacker was suspended from school for one year. However, his infraction was later expunged from all school records.

Still a Culture of Denial

Although Title IX – known as the Education Amendments Act, which bars discrimination on the basis of sex – was passed in 1972, nearly a half century later little appears to have changed. Victims of sexual assault often remain silent because even when they speak up, no one pays a price.

In a country where Brett Kavanaugh may avoid a formal FBI investigation, and a second alleged sexual abuser (does the name Clarence Thomas ring a bell?) could don the robes of the Supreme Court, one can only be left wondering when, and if, conditions will ever change for the victims.

“Victims get judged and blamed and put down," said Ellie. "People will always push back against the accusations you make, and it’s hard to come forward when you’re not positive the people listening will really hear you."

Ford is now receiving death threats. McConnell said she skipped class so she wouldn’t run into her abuser. Ellie is still afraid of her attacker. And Garza continues to wonder, had she done something different that night, whether she could have saved her herself the emotional trauma.

These are just a few stories out of millions. I have been a victim of sexual assault. She has been a victim of sexual assault. Have you?