This is the first installment in a two-part review Gareth Dale's new book, "Karl Polanyi: A Life on the Left (Columbia University Press, 381 pp.)

What a splendid era this was going to be, with one remaining superpower spreading capitalism and liberal democracy around the world. Instead, democracy and capitalism seem increasingly incompatible. Global capitalism has escaped the bounds of the postwar mixed economy that had reconciled dynamism with security through the regulation of finance, the empowerment of labor, a welfare state, and elements of public ownership. Wealth has crowded out citizenship, producing greater concentration of both income and influence, as well as loss of faith in democracy. The result is an economy of extreme inequality and instability, organized less for the many than for the few.

Not surprisingly, the many have reacted. To the chagrin of those who look to the democratic left to restrain markets, the reaction is mostly right-wing populist. And “populist” understates the nature of this reaction, whose nationalist rhetoric, principles, and practices border on neofascism. An increased flow of migrants, another feature of globalism, has compounded the anger of economically stressed locals who want to Make America (France, Norway, Hungary, Finland…) Great Again. This is occurring not just in weakly democratic nations such as Poland and Turkey, but in the established democracies—Britain, America, France, even social-democratic Scandinavia.

We have been here before. During the period between the two world wars, free-market liberals governing Britain, France, and the U.S. tried to restore the pre–World War I laissez-faire system. They resurrected the gold standard and put war debts and reparations ahead of economic recovery. It was an era of free trade and rampant speculation, with no controls on private capital. The result was a decade of economic insecurity ending in depression, a weakening of parliamentary democracy, and fascist backlash. Right up until the German election of July 1932, when the Nazis became the largest party in the Reichstag, the pre-Hitler governing coalition was practicing the economic austerity commended by Germany’s creditors.

The great prophet of how market forces taken to an extreme destroy both democracy and a functioning economy was not Karl Marx but Karl Polanyi. Marx expected the crisis of capitalism to end in universal worker revolt and communism. Polanyi, with nearly a century more history to draw on, appreciated that the greater likelihood was fascism.

As Polanyi demonstrated in his masterwork The Great Transformation (1944), when markets become “dis-embedded” from their societies and create severe social dislocations, people eventually revolt. Polanyi saw the catastrophe of World War I, the interwar period, the Great Depression, fascism, and World War II as the logical culmination of market forces overwhelming society—“the utopian endeavor of economic liberalism to set up a self-regulating market system” that began in nineteenth-century England. This was a deliberate choice, he insisted, not a reversion to a natural economic state. Market society, Polanyi persuasively demonstrated, could only exist because of deliberate government action defining property rights, terms of labor, trade, and finance. “Laissez faire,” he impishly wrote, “was planned.”

Polanyi believed that the only way politically to temper the destructive influence of organized capital and its ultra-market ideology was with highly mobilized, shrewd, and sophisticated worker movements. He concluded this not from Marxist economic theory but from close observation of interwar Europe’s most successful experiment in municipal socialism: Red Vienna, where he worked as an economic journalist in the 1920s. And for a time in the post–World War II era, the entire West had an egalitarian form of capitalism built on the strength of the democratic state and underpinned by strong labor movements. But since the era of Thatcher and Reagan that countervailing power has been crushed, with predictable results.

In The Great Transformation, Polanyi emphasized that the core imperatives of nineteenth-century classical liberalism were free trade, the idea that labor had to “find its price on the market,” and enforcement of the gold standard. Today’s equivalents are uncannily similar. We have an ever more intense push for deregulated trade, the better to destroy the remnants of managed capitalism; and the dismantling of what remains of labor market safeguards to increase profits for multinational corporations. In place of the gold standard—whose nineteenth-century function was to force nations to put “sound money” and the interests of bondholders ahead of real economic well-being—we have austerity policies enforced by the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, with the American Federal Reserve tightening credit at the first signs of inflation.

This unholy trinity of economic policies that Polanyi identified is not working any more now than it did in the 1920s. They are practical failures, as economics, as social policy, and as politics. Polanyi’s historical analysis, in both earlier writings and The Great Transformation, has been vindicated three times, first by the events that culminated in World War II, then by the temporary containment of laissez-faire with resurgent democratic prosperity during the postwar boom, and now again by the restoration of primal economic liberalism and neofascist reaction to it. This should be the right sort of Polanyi moment; instead it is the wrong sort.

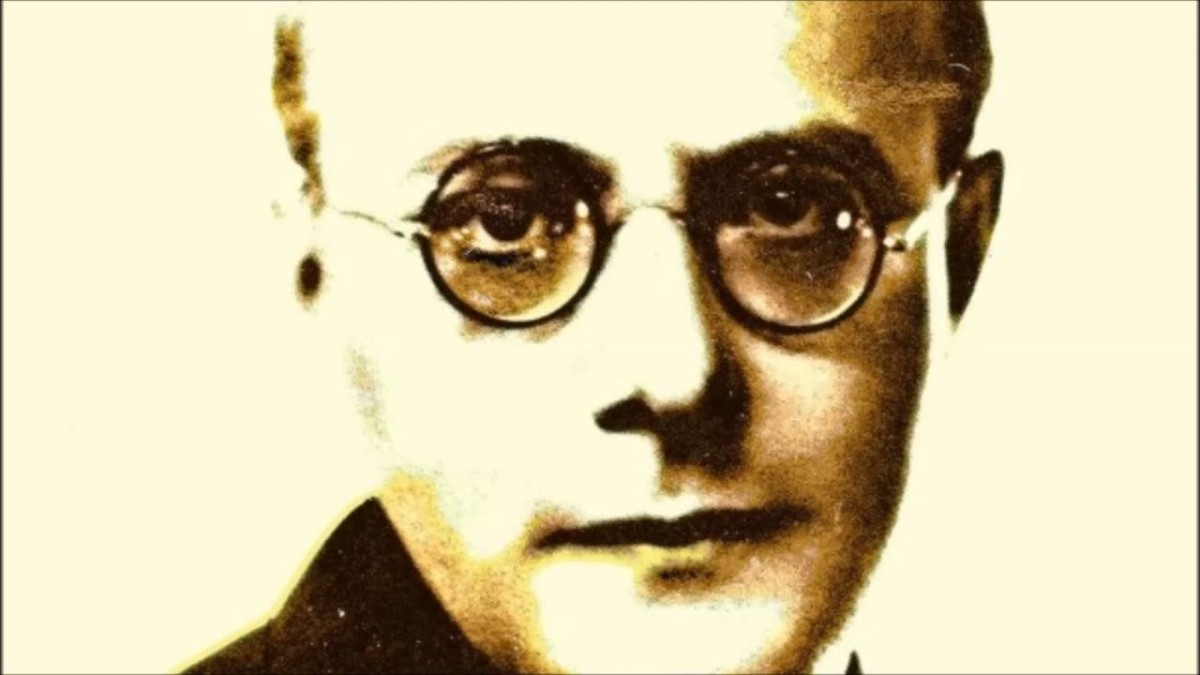

Gareth Dale’s intellectual biography, Karl Polanyi: A Life on the Left, does a fine job of exploring the man, his work, and the political and intellectual setting in which he developed. This is not the first Polanyi biography, but it is the most comprehensive. Dale, a political scientist who teaches at Brunel University in London, also wrote an earlier book, Karl Polanyi: The Limits of the Market (2010), on his economics.

Polanyi was born in 1886 in Vienna to an illustrious Jewish family. His father, Mihály Pollacsek, came from the Carpathian region of the Hapsburg Empire and acquired a Swiss engineering degree. He was a contractor for the empire’s growing rail system. In the late 1880s, Mihály moved the family to Budapest, according to the Polanyi Archive. He magyarized the children’s family name to Polanyi in 1904, the same year Karl began studies at the University of Budapest, though he kept his own surname. Karl’s mother, Cecile, the well-educated daughter of a Vilna rabbi, was a pioneering feminist. She founded a women’s college in 1912, wrote for German-language periodicals in Budapest and Berlin, and presided over one of Budapest’s literary salons.

At home, German and Hungarian were spoken (along with French “at table”), and English was learned, Dale reports. The five Polanyi children also studied Greek and Latin. In the quarter-century before World War I, Budapest was an oasis of liberal tolerance. As in Vienna, Berlin, and Prague, a large proportion of the professional and cultural elite consisted of assimilated Jews. In the mid-1890s, Dale notes, “the Jewish faith was accorded the same privileges as the Christian denominations, and Jewish representatives were accorded seats in the upper house of parliament.”

Drawing on interviews and correspondence as well as published writings, Dale vividly evokes the era. Polanyi’s milieu in Budapest, known as the Great Generation, included activists and social theorists such as his mentor, Oscar Jaszi; Karl Mannheim; the Marxist Georg Lukács; Karl’s younger brother and ideological sparring partner, the libertarian Michael Polanyi; the physicists Leo Szilard and Edward Teller; the mathematician John von Neumann; and the composers Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály, among many others. In this hothouse Polanyi thrived, attending the Minta Gymnasium, one of the city’s best, and then the University of Budapest. He was expelled in 1907 following a shoving match in which anti-Semitic right-wingers disrupted a lecture by a popular leftist professor, Gyula Pikler. He had to finish his doctor of law degree in 1908 at the provincial University of Kolozsvár (today Cluj in Romania). There, he was a founder of the left-humanist Galilei Circle and later served on the editorial board of its journal.

Polanyi became a leading member of Jaszi’s political party, the Radicals, and was named its general secretary in 1918. He was drawn to the Christian socialism of Robert Owen and Richard Tawney and the guild socialism of G.D.H. Cole. He mused about a fusion of Marxism and Christianity. Polanyi is best classified as a left-wing social democrat—but a lifelong skeptic of the possibility that a capitalist society would ever tolerate a hybrid economic system.

After World War I broke out, Polanyi enlisted as a cavalry officer. When he came home in late 1917, suffering from malnutrition, depression, and typhus, Budapest was in the throes of a chaotic conflict between the left and the right. In 1918 the Hungarian government made a separate peace with the Allies, breaking with Vienna and hoping to create a liberal republic. Events in the streets overtook parliamentary jockeying, and the Communist leader Béla Kun proclaimed what turned out to be a short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic.

Polanyi decamped for Vienna, both to recover his health and to get off the political front lines. There he found his calling as a high-level economics journalist and the love of his life, Ilona Duczynska, a Polish-born radical well to his left. Their daughter, Kari, born in 1923, recalls, as a preteen, clipping marked-up newspaper articles in three languages for her father. At age ninety-four, she continues to help direct the Polanyi Archive in Montreal.

Central Europe’s equivalent of The Economist, the weekly Österreichische Volkswirt, hired Polanyi in 1924 as a writer on international affairs. He continued his quest for a feasible socialism, engaging with others on the left and challenging the right in ongoing arguments with the free-market theorist Ludwig von Mises. The debates, published in agonizing detail, turned on whether a socialist economy was capable of efficient pricing. Mises insisted it was not. Polanyi argued that a decentralized form of worker-led socialism could price necessities with good-enough accuracy. He ultimately concluded, Dale recounts, that these abstruse technical arguments had been a waste of his time.1

A practical answer to the debate with Mises was playing out in Red Vienna. Well-mobilized workers kept socialist municipal governments in power for nearly sixteen years after World War I. Gas, water, and electricity were provided by the government, which also built working-class housing financed by taxes on the rich—including a tax on servants. There were family allowances for parents and municipal unemployment insurance for the trade unions. None of this undermined the efficiency of Austria’s private economy, which was far more endangered by the hapless policies of economic austerity that were criticized by Polanyi. After 1927, unemployment relentlessly increased and wages fell, which helped bring to power in 1932–1933 an Austrofascist government.

The second installment in the series will appear tomorrow.

Originally published by The New York Review of Books

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments