Labor Day: it may conjure up the image of a restful day off work or a crowded sun-drenched beach. But in Berlin, the German capital, it means a sudden boost of police personnel to quell the unrest of not-just-another holiday.

Since the 1980s, Berlin’s version of May 1 has marked an eventful, troublesome expression of the sociopolitical concerns of its citizens, and a laundry list of minor property damage by its closure.

This year, protests in the city are centered on the E.U. crisis, which it seems may finally be reaching Germany -- long seen as a pillar of stability amid the southern economies crumbling around it. For years, Germans have watched neighboring nations struggle in debt, and offered more debt, in the form of bailouts, as a solution. May 1 is the day people voice their frustration.

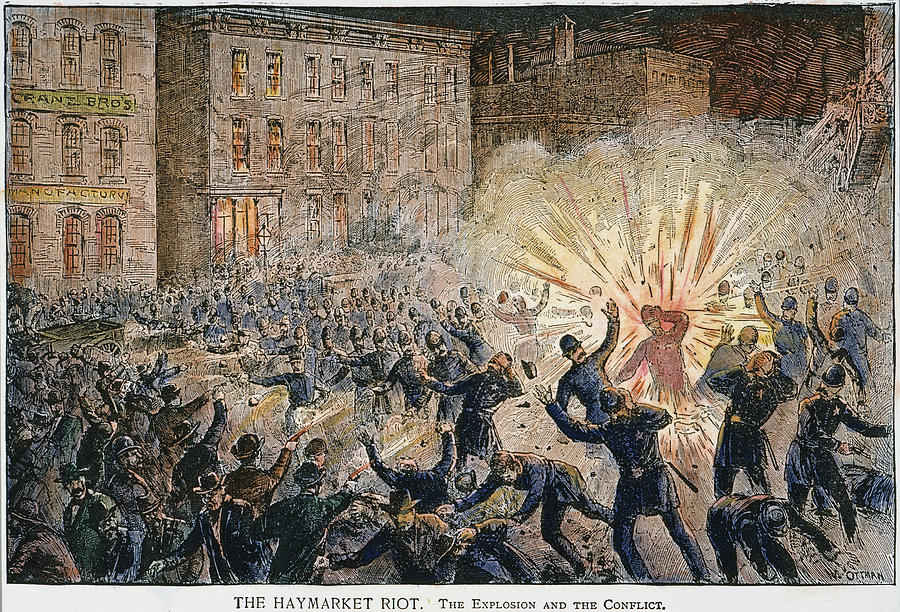

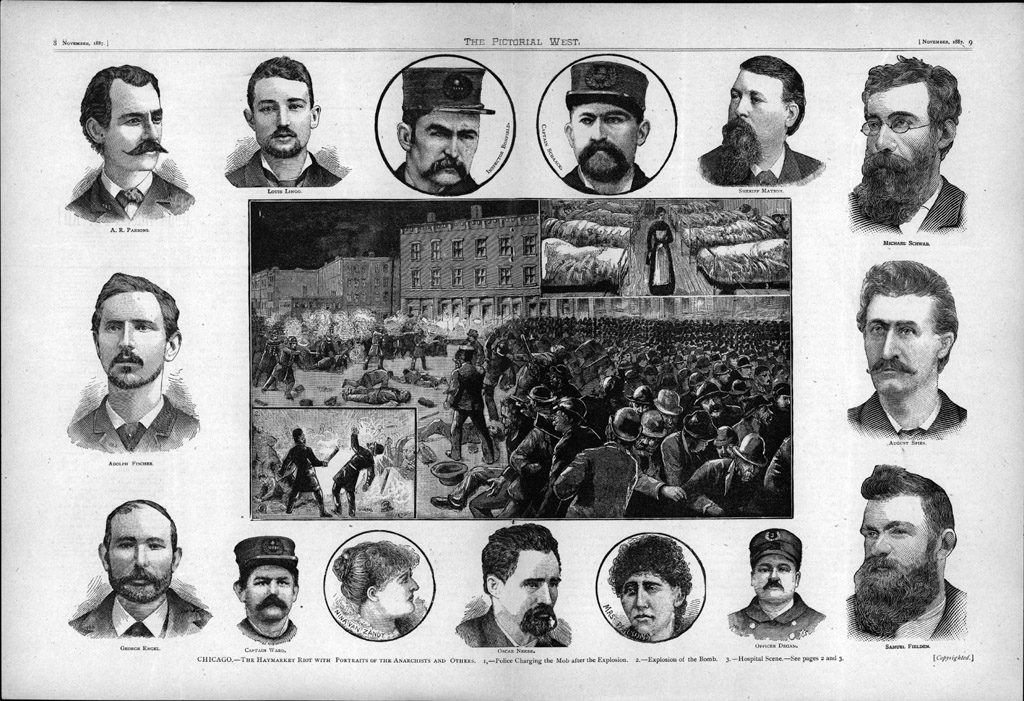

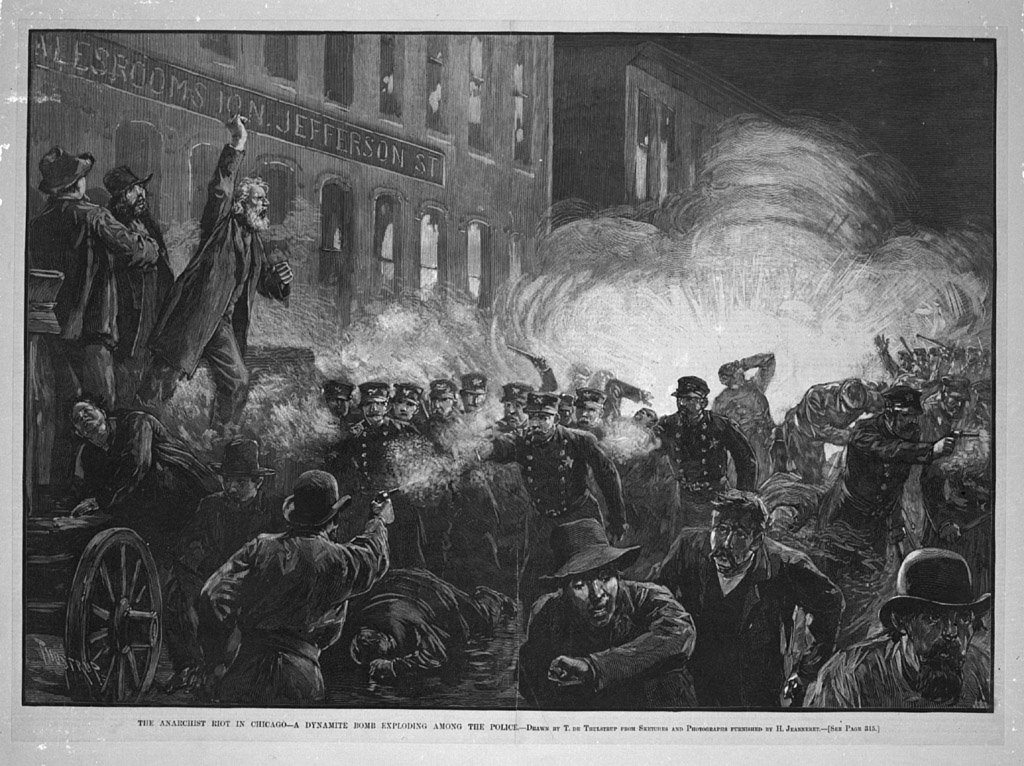

But gaining this freedom to protest May Day was no peaceful road. On May 4, 1886, in Chicago, seven police officers were killed along with four civilians in an explosion at Haymarket Square. The rally in support of the eight-hour workweek, which ended with the result of four accused anarchists being hanged, represented the budding of support for the labor movement in America and worldwide. In 1890 the date grew into what we now know as International Workers Day.

From Seven Police to 7000

Kreuzberg has always been one of the most densely populated and industrial districts of Berlin. Since the 1950s, it has been a melting pot for diverse ethnic families that came to Germany to rebuild Berlin after WWII. By the 1980s, the celebration of May Day in West Berlin was an affair largely organized by trade unions, and left little room for demonstrations by factions of the left.

But the tradition of violent May Day protests started when riots broke out on May 1, 1987, between left-wing autonomists and police. In 1988, left-wing groups in Kreuzberg organized their first official May Day demonstration -- initiating a culture of rioting as protesters clashed with police, which has been a neighborhood tradition ever since.

May Day was no longer just about unions. Over the years, the demonstrations became a reflection of the political conflicts facing Europeans at the time. From mottos like “No liberation without revolution” in the 1980s, to “End the crisis, abolish capitalism” in the late 2000s, the fevered pitch of Berlin's leftists became a May Day institution.

In 2001, when Berlin's conservative government tried to ban the protest, it only strengthened protesters' commitment to demonstrate -- whether the city deemed it legal or not. This made bringing riot police from other parts of Germany to Berlin a necessity, and heaped unwanted attention on local police who were forced to handle the chaos.

This year, the city government brought in an estimated 7,000 auxiliary officials from across Germany to aid in controlling the action.

The Price of Transparency

What's new this year is the filming of “overview images” of the various events, which will be captured by helicopter and from vantage points on residential buildings. Berlin Police Chief Klaus Kandt said at a press conference on April 26 that no images will be stored. Kandt maintained that cameras are in use only as a source of triage for stationing police forces for quick security response.

The police have also revealed the exact known routes of the marches -- both by the left and the right wing -- something authorities had not done previously because they feared it would give neo-Nazi demonstrators and anti-fascist protesters ammunition to square off violently with one another, since they could easily block each other's routes. “That’s the price of transparency,” said Kandt.

About 30 rallies and demonstrations have been registered in the capital, with participation expected by neo-Nazis aligned with the National Democratic Party, and by members of Anti-Fascist Revolutionary Action Berlin (ARAB).

Like most years, authorities will devote special attention to the “Revolutionary May 1 Demo,” which kicks off at 6pm in Kreuzberg and has witnessed repeated riots in the past. This year, the demo’s left-wing organizers want to pull out of Kreuzberg and move towards the city center, where they expect up to 10,000 participants. According to police, the march may end in a standoff at the European Commission office, located at Pariser Platz in front of the Brandenburg Gate.

The May Day demonstrations strike at core topics facing Berliners, such as gentrification, rising property values and the anti-bailout sentiment that is propelled by the current E.U. crisis. “The aim is to protest against German imperialism, E.U. crisis policy, and a massive impoverishment of large parts of the European population,” states the ARAB website.

Bit by bit, Berlin is allowing corporations and wealthy expatriates to change the industrial landscape of its city. And as people in working class neighborhoods see the property values rise, more communities of workers, students, artists and activists may turn to May Day as a vessel for change.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments