This is part one of a series exploring the concept of means testing and its effect on the people it’s meant to help. Stay tuned for parts two and three.

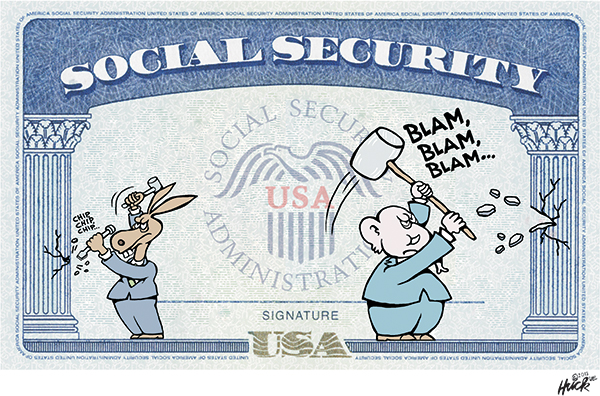

On paper, the concept of means testing eligibility for publicly funded safety net programs makes sense: If an applicant is affluent, they don’t need taxpayer-funded services they could otherwise pay for out of pocket, and money for those services is better spent when reserved exclusively for those who are truly in need. So before an applicant can qualify for benefits, the state (or county) needs to test an applicant to determine if they have the means to meet their own needs.

However, each entity can have their own means testing systems for applicants, these entities rarely talk to each other, and needy applicants can find themselves in a game of Hot Potato as they get passed from one agency to another and given advice that contradicts what another agency advised them to do. Any misstep along the way could get an applicant’s paperwork sent to the bottom of the pile, risking long, agonizing periods of waiting for often understaffed and under-funded agencies to catch up to an applicant.

It’s not hard to imagine how navigating this labyrinthian bureaucracy can leave applicants for public safety net programs feeling exhausted and defeated. This is especially true for those with disabilities.

“Means testing is ruining my life.”

In California’s Bay Area, Leah Fitzgerald (Full disclosure: “Leah Fitzgerald” is a relative of the author, and the name is a pseudonym requested by the subject who is uncomfortable using her real name out of fear of permanently losing her benefits) has been relying on a combination of both California’s Medicaid program (commonly referred to as “Medi-Cal”) and Medicare Extra Help to obtain her medication. Since her father died, she’s also been receiving Social Security Survivors’ Benefits.

Fitzgerald was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia following a psychotic break in 1999 that was brought on by an attempted sexual assault. While doctors no longer use or recognize that diagnosis, Fitzgerald has been prescribed a laundry list of expensive medications to manage her condition, including antipsychotics like Ziprasidone and Trifluoperazine, and other medications to manage the side effects of those medications like Metformin – an anti-diabetic medication, as antipsychotics often result in weight gain – and Topamax, which prevents seizures and headaches.

Normally, Fitzgerald is able to access her medication through Medi-Cal. And until recently, Fitzgerald’s coverage was linked to the California Department of Health Care Services’ (DHCS) Working Disabled Program, meaning she has to prove to the state that she’s working in order to obtain her medication (Fitzgerald did this by watering plants for $1 a month). This shifted her at one point to a Medi-Cal “Share Of Cost” (SOC) plan in which she would be required to pay $1,300 per month before Medi-Cal covered the cost of her medications.

When a pro bono attorney from Bay Area Legal Aid tried to shift her away from the SOC plan toward a Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI Medi-Cal) plan, she had to sign a form agreeing to withdraw from the Working Disabled Program in order to qualify for the MAGI plan. But after doing so, Fitzgerald received a letter on July 11 from Kaiser Permanente – which she uses to access her Medi-Cal benefits – saying that her Medi-Cal coverage had expired as of July 1. This means that currently, a woman with a debilitating mental health condition deemed unable to work is now on the hook for thousands of dollars a month to pay for the medication she needs to function.

“Means testing is ruining my life,” Fitzgerald said. “Although I have been told my schizophrenia is moderate, it is insulting for a high-functioning person like me, or for anybody else, to be trapped into poverty.”

“Some people are eligible for Medicare, as long as they stay disabled and are unable to work, but paying for prescriptions on Medicare without Medi-Cal would still require a 20% copay, which could be as much as $500 a month or more,” she added.

Fitzgerald contacted the offices of US Senator Alex Padilla and Rep. Barbara Lee – whose district she resides in – in an attempt to get them to advocate on her behalf. While she was only able to leave a message with one of Sen. Padilla’s staffers, Lee’s office told Fitzgerald to contact Medi-Cal, which she has already done and continues to do. Lee’s office did not return Occupy.com’s request for comment, and a staffer for Sen. Padilla told Occupy.com that while the senator may consider making a Congressional inquiry, no action has yet been taken.

Despite her condition, Fitzgerald is highly educated and attended classes at Ohlone College in Fremont, California up until the Covid-19 pandemic. She has two associate’s degrees: One in human development studies, and another in social science. She also has a certificate of completion for a series of courses in sociology, and at one point was president of the school’s psychology club. She aspires to one day be a psychologist and be financially independent, but in order to continue to qualify for benefits in the meantime, she has to keep less than $2,000 in assets, which makes it impossible for her to save.

“In California, $2,000 is nothing,” Fitzgerald said. “I am sick and tired of being means tested. I want to be able to save and have a few thousand in the bank. I could honestly understand some means testing if it’s a budgeting thing, but $2,000 is ridiculous.”

Fitzgerald contends that the rigorous means testing she’s subjected to in order to receive benefits intrudes well beyond her financial situation and into her personal life, as having a spouse would likely put her above the income threshold to qualify for Medi-Cal.

“I don’t believe in sex before marriage, and my medication is too expensive to pay for out of pocket. So when you combine that with the government requiring me to be single, I’m now a 42-year-old virgin,” Fitzgerald said.

“It’s a snarl. We’re stuck, basically.”

Fitzgerald’s mother, Kim (“Kim” is also a pseudonym to protect Fitzgerald’s identity), who is a recently retired occupational therapist, has been trying to help Leah navigate the confusing bureaucratic obstacles of Medi-Cal’s means testing requirements before her daughter’s current supply of medication runs out. Kim, who herself has no mental health diagnoses, told Occupy.com that the system is stressful and anxiety-inducing even on a second-hand level.

“My stomach is in knots. I’m just feeling a lot of physical discomfort trying to process this,” Kim said.

“I’m like [Leah]. I have to take breaks. You have to feel this internal strength and be ready to do that. Sometimes it’s like, I just need to do something for my digestion first to prepare for all this,” she continued. “[Leah] has been so overwhelmed that the lawyer is now sending me emails. It’s giving [Leah] a break. We’re just waiting for the lawyer, waiting for the county, it’s a snarl. We’re stuck, basically.”

While her Medi-Cal eligibility is in limbo, Leah has been rationing her medication to make her supply stretch further. She’s recently been having conversations with a researcher at the National Institute of Mental Health about a six-month inpatient schizophrenia study where she would be observed after being taken off medication, in order to see if she could have her medication reduced safely.

“I tried to skip the dose of my Trifluoperazine this morning and only take it in the evening, but I had too much anxiety,” Fitzgerald said on July 20. “I’m rationing the Metformin, and I’m rationing the Topamax, because the consequences of taking less are worth it. However, taking less of the antipsychotics could send me to the mental hospital.”

“I’m on a number of health insurance plans that all work together, and I’m tired of having to be the one to coordinate all of this,” Fitzgerald added. “I emailed my lawyer today and said, ‘I don’t think I can continue to do this.’”

Republicans want to make means testing even stricter

While Leah and her mother are mired in a sludge of means testing bureaucracy in California, they could be even worse off in other states, and their situation could be exacerbated under a Republican administration. In July, Georgia became the first state to allow for an expansion of Medicaid benefits, but only if applicants can prove they work or are in job training for at least 80 hours each month. In Kentucky, Attorney General Daniel Cameron, who is the Republican gubernatorial nominee, pledged to implement Medicaid work requirements if elected. Arkansas Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders has announced similar plans. Republicans in Ohio also included work requirements in their latest budget agreement.

The only thing preventing these states from implementing strict new work requirements for Medicaid recipients is the Biden administration’s Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which is unlikely to approve any state’s applications to modify their Medicaid programs in this way. The Trump administration approved 13 such modifications, but federal judges struck down two and Biden’s HHS struck down another 10. House Republicans attempted to get Medicaid work requirements into the latest debt ceiling negotiations, but failed. A 2023 study by the Kaiser Family Foundation estimated that these changes would remove approximately one million Americans from current Medicaid rolls.

Rather than implement even more arduous obstacles that gatekeep Medicaid from the needy, Kim Fitzgerald hopes lawmakers will find a way to streamline the Medi-Cal system to make it easier for applicants – particularly those with disabilities – to navigate it.

“All these systems are apparently not talking with each other,” Kim said. “There should be at least one person that’s looking to integrate all of this… it doesn’t seem like it should be difficult to create that system and get it in place. This should not be required for people with mental health issues, or anybody.”

“The world is psychotic,” Kim added. “[Leah] is just doing what she has to do to live in it.”

Carl Gibson is an independent journalist whose work has been published in CNN, the Guardian, the Washington Post, the Houston Chronicle, the Louisville Courier-Journal, Barron’s, Business Insider, the Independent, and NPR, among others. Follow him on Bluesky @crgibs.bsky.social.