On April 20, 1999, two high school students opened fire at Columbine High School in Colorado, killing 13 people and wounding more than 20. That day became a grim marker in a line of mass murders that would later include Virginia Tech, Sandy Hook, Parkland, and dozens of other, lesser-known shootings.

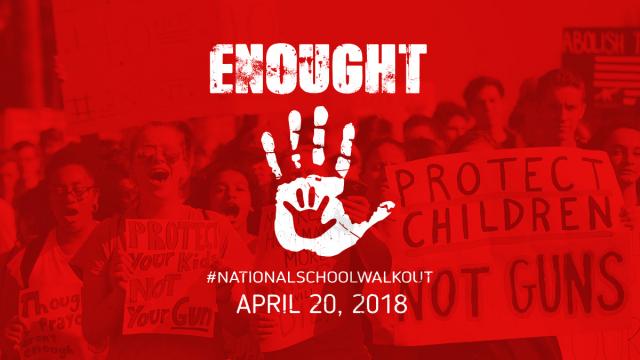

Friday, April 20, 2018, on the 19th anniversary of Columbine, students will walk out of classrooms to protest for gun reform. The National School Walkout is calling attention to the broken promise of “never again” — that after Columbine, the mass shootings continued.

More than 2,600 walkouts are planned across the country on Friday. Students are encouraged to leave their classrooms and gather at 10 am to hold a moment of silence for the victims of gun violence, setting aside 13 seconds to honor those killed at Columbine. The walkout is encouraging day-long protests, both on campus and outside of school, including marches, speakers, and voter registration drives. Participants are encouraged to wear orange, the color of the anti-gun violence movement.

The April 20 walkout will be a test for the staying power of this new wave of activism. The Parkland shooting has faded from the headlines in the weeks since the March for Our Lives, and Friday’s rally is one of the last coordinated, nationwide gun control efforts on the calendar.

“April 20 isn’t the end of this,” Lane Murdock, a high school sophomore, who helped jump-start the National School Walkout, told Vox last month. “April 20 is the launch. We want to make sure we take all this momentum, power, and interest and turn it into concrete, actual change.”

What to know about the National School Walkout

This idea for a National School Walkout began with a high school sophomore from Connecticut. Lane Murdock, 16, of Ridgefield High School, started an online petition after the Parkland shooting. She felt America was becoming numb to mass shootings. She was tired of it. “But I also just felt really powerless,” she told Vox in March. So, she thought, “What could I do to help other kids who felt really powerless?”

Murdock created her protest independent of the March 14 National School walkout, which the Women’s March helped organize. That walkout, a month after the Parkland shooting, honored the 17 victims killed and pushed for gun control measures.

Indivisible, a progressive organizing group founded after the 2016 election, is backing the April 20 walkout and helping Murdock and some of her fellow students organize — and some students indicated that the April 20 event is a bit more of an open political push for gun reform. But organizations, including the Women’s March, that participated in last month’s walkout are working together to promote this rally.

The walkout will begin at 10 am local time for all students. Most schools will host a moment of silence at the start of the walkout, followed by speakers or rallies. The National School Walkout is calling for the protest to last the length of the school day. It’s leaving it up to students how to fill that time, though organizers are emphasizing voter registration drives.

How schools are staging their walkouts

Students will get up from their desks and file out of classrooms at 10 am in each time zone. Some are organizing larger protests in cities, bringing together teens and other community members to rally in public squares. Other schools will host quieter affairs: moments of silence, a few speeches, voter registration in between class periods.

Students in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, are teaming up to host a rally in the city’s Peace and Justice Plaza. At Benjamin Cardozo High School in Queens, New York, teens will walk out with signs and banners. At Lincoln East High School in Lincoln, Nebraska, students will host a moment of silence and student speakers for a class period. The week leading up to the walkout, they’re hosting a voter registration drive, set up as students buy their prom tickets.

Diego Quesada, an 18-year-old senior at Ronald Reagan High School in San Antonio, Texas, said that teachers are treating the walkout as an unexcused absence and will deduct points for tests or other assignments for some students who aren’t present. Still, he expects at least 100 students to participate.

As a school in central Texas, its community is divided, he said — though not as obviously as it might seem. He knows Republican gun owners who support at least some gun control measures. Still, Quesada said the organizers don’t want to shut out dissent. “Instead of just trying to shut out an entire opinion, especially in our state, we decided we’re going to address both issues,” he said. They’ll host a week of kindness that will focus on mental health and school safety issues that more conservative voices tend to champion and use the walkout to push more explicitly for new gun laws.

The point of it all, Quesada said, is open dialogue. Whatever his fellow students’ political positions, they’re all affected by the issue. The same day as the Parkland shooting, a bullet box was found in their high school. The year before, an active shooter threat put the school on lockdown.

“That is normal to me — fire drills followed by the lockdown drill,” Quesada said, of students who grew up post-Columbine. “Somehow it is socially acceptable that we had to walk out of our school in a practice drill holding our hands up; that shouldn’t be acceptable. I think that’s what people are fed up about. There needs to be a change.”

The turnout might not be as large as the March 14 walkout at Benjamin Cardozo High School, 16-year-old junior Ramija Alam said, but students are going ahead with the walkout anyway to show solidarity with the national movement. “We’ve had gun threats, and we’ve had bomb threats even,” she said. “It kind of puts a lot of fear in us when we go to school.”

Alam said she thinks she and her fellow students are motivated on this issue but have also become more politically active after the 2016 election. The gun control movement is just one part of it. “It’s not okay for us to just sit down and let everything happen as it is because there is something we can do about it,” she said.

Teenage activism may have gotten quieter — but don’t underestimate it

Parkland students ignited a new push for gun control in the wake of the shooting at their school that left 17 people dead. This flurry of activism began with a student walkout on March 14 and asserted its power with the massive March for Our Lives that brought thousands to the streets of Washington, DC, and other cities, large and small, and across the country.

But the message of “never again,” still powerful, has stalled a bit in recent weeks. A Town Hall for Our Lives on April 7 — a push to get legislators to talk about gun control with constituents — put some public pressure on lawmakers, but it didn’t break through the way other organizing efforts did.

“That’s definitely something I think we’ve all noticed,” Murdock said of the fading media attention on the cause. “And we’ve been ready for it for a while.”

They’re ready for it because April 20 marks, in some ways, the end of one phase of activism — of the protests and public anger. Now begins the slog: political organizing for gun reform. There are very real signs that even if it’s not as loud or as urgent, these efforts are taking root.

The voter registration drives are critical, Murdock said last week as she was prepping for her own high school walkout, because getting young people to vote will guarantee that this is not “just a moment, but a movement.”

Emma Jewell, a 17-year-old senior at Lincoln East High School in Nebraska, said the voter registration was perhaps as important as the walkout. “I think there’s a lot of students who might not understand they have some political power that they haven’t harnessed, so we’re going to try to take advantage of that,” she said. “My biggest, greatest hope is that the issue of gun violence will become a midterm issue in 2018.”

The walkout is also helping to build the infrastructure students will need to continue grassroots activism. Murdock said students across the country are now organizing local chapters, some under the banner of National School Walkout. After the march, she’ll be working with others to empower these groups to push for gun control legislation not just on the federal level, but in their communities, cities, and states.

These groups are uniting students from across schools and communities. In New York, NYC Says Enough is bringing students together from a handful of high schools to walk out together. Students in Richmond, Virginia, are also teaming up for a march to the Virginia Capitol.

And, in a month after the March 14 walkout, their efforts have become more professionalized. Teenagers are sending press releases and putting together press packets.

“The chapters are going to be our key after this,” Murdock said, especially as the 2018 elections approach. “It’s going to be making sure we can have mass calls to action, and continually talking about our message of commonsense gun control — and student empowerment.”