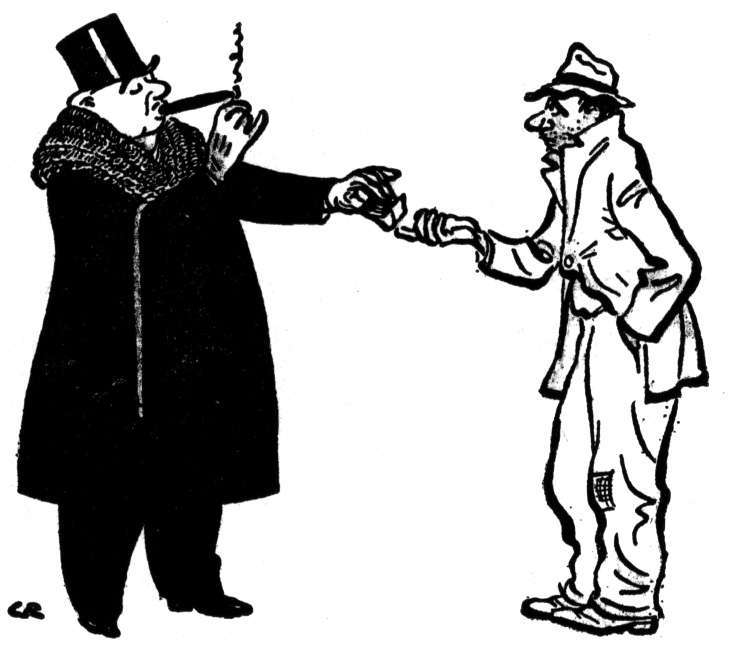

"But equal opportunity for all cannot possibly and by the very same phrase mean unlimited license for the cunning and the greedy who take advantage of that equal opportunity to establish special or, in other words, unlimited individual privileges, and the power that goes with the same, the while the remaining 90 to 95% per cent of the citizens of this land trudge in comparative want."

Despite the poor reception of "Tragic America" (1932), the American novelist Theodore Dreiser remained an unflappable bulwark — perhaps a stoic — not unlike the main characters of his two posthumously published novels. He was certainly not going to be intimidated by accusations of creating “class war” or a “hymn of hate.” For then as now, those deemed “radically American” were already used to corporate and elite resentment: namely, those who argued, as did Dreiser, that “the common people (more than 99% of the population) never have prosperity” while the 1% enjoyed “a state of prosperity.” Digging in his heels, Dreiser crafted a vigorous argument against U.S. engagement in World War II, "America is Worth Saving" (1941). How asinine to engage in war when there was so much more to fix at home — most notably, high unemployment and widespread poverty. Although he was later to change his mind on the war, especially with the subsequent German invasion of Russia and Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, there are nonetheless prescient ideas which are curiously as relevant to us in 2013 as they were in 1941.

Dreiser was quick to scorn America’s eager support for Britain — particularly when ”the British empire was built on the theory of the dominant 3 per cent”: a theory and practice best avoided by everyone. Let’s cut beneath all the fine purple prose on the value of “British democracy and liberty.” What was the real truth? That a vast majority of Britons were struggling to rise above squalor — or at least according to his British contemporaries, George Bernard Shaw and the young radical, George Orwell. Here, Dreiser would quote copiously from the latter’s Engelsian account of Northern poverty, "Road to Wigan Pier" (1937).

Yet, even worse off were the imperial subjects of Britain — beginning with Ireland, a colony in all but name. As it was understood then, the English “shoot first and talk afterward — ask any Irishman.” Dreiser probably had in mind the Great Famine of 1848 and the Easter Rising of 1916, both of which were widely regarded by the Irish as examples of British “genocide.” Unlike the anti-war, America-First Charles Lindbergh, Dreiser was far from racist, and as such, lambasted the British presence in Burma, China, India, South Africa, and Egypt (where “the present living conditions...are among the worst in the world”). There was no question that the Indian Mutiny of 1857 demonstrated “a savagery never surpassed by the Nazis,” with men, women, and children tortured, burned, hanged, and peppered. It’s a judgment that aligned with Maud Gonne’s own damning assessment of Britain in 1938: that ”No more can the British Empire stand or go without famine in Ireland, opium in China, torture in India, pauperism in England, disturbance and disorder in Europe and robbery everywhere.”

In truth, there was only a nominal difference between the German and Italian monopolists on the one hand, and the English and American on the other: whereas “the former frankly call it conquest and the latter call it “protection.” Or to put it more boldly, “England’s ‘protection” was “exactly the same as England’s domination,” and the conflict between England and Germany little more than “a scrap between Hitlerdum and Hitlerdee.” (A fascist by any other name would smell just as foul — to put a spin on Shakespeare!)

And anyway, Dreiser adds, the Nazi regime itself was largely created and financed by “Big German capitalists” (e.g., Krupp, Siemens, Thyssen, Bosch, Voegler), many of whom enjoyed partnerships with American, British, and French corporations and banks. All told, the war against Hitler was a vast collusion of 1% power players who desired nothing less than “to sell democracy out”: a phenomenon not entirely different from our own subsequent wars — including our propping of royalist and wealthy dictatorships in Latin America and the Middle East.

So why were Americans clamoring to support Britain? Why were they so gaga over this bad, mad, “masochistic” romance, begging Britney — oops, Britannia — to “Kick me again, daddy?” Why this absolutely ludicrous “sympathy” for “the lords and ladies and money-stuffed merchants of the south of England?” The fact was that American cultural elites remained as lovestruck with Britain as ever — gushing over the glamorous unions of English and American aristocrats, corporate magnates, and bankers: all of whom were in bed with each other, literally and figuratively. As such, there was no reason for the ordinary American to support the military endeavors of hoity-toity folks who intermarried, conducted business amongst themselves, and financed each other.

Interestingly, nearly a century later, things have remained much the same with a (re)emerging North Atlantic ruling class as recently described in “The Global Power Project.” Perhaps that’s why our 5% are obsessed with Kate and Wills (as well as the royal baby to be), salivating all the while over Downton Abbey or other any other film involving a stately-manor as if longing for the days when Britannia ruled the seas (and the “darkies”) while the locals beamed, bowed, and curtsied.

But of course, there was that most inconvenient truth — our collective “save-the-world-complex.” You see, “Geography gave Americans our pathological concern about Christianity, Democracy in Cuba, Democracy in Europe — great abstract causes for which we will give and fight without pausing to think who is really profiting by it, or that these things cannot be imposed from without.” Hence, too, the initial fervor for our so-called “War on Terror” aka “Operation Iraqi Freedom” expressed by those who failed to see the utility (and irony) of imposing “democracy” while the exceptionally affluent likes of Bush, Cheney, Feinstein, Woolsey, and other 1%ers profited from lucrative war contracts.

At the same time, for all our collective hand-wringing, Dreiser muses, we seldom help out in any meaningful way. Take the purported sympathy for the Chinese: yes, we love them so much that “we long supplied Japan with the iron to torture the Chinese a little more, and the oil to take Japanese planes to the altitudes from which from which it can most effectively be hurled.” Instead, we Americans assuaged our consciences by sending them “plenty of missionaries to make them Christian.”

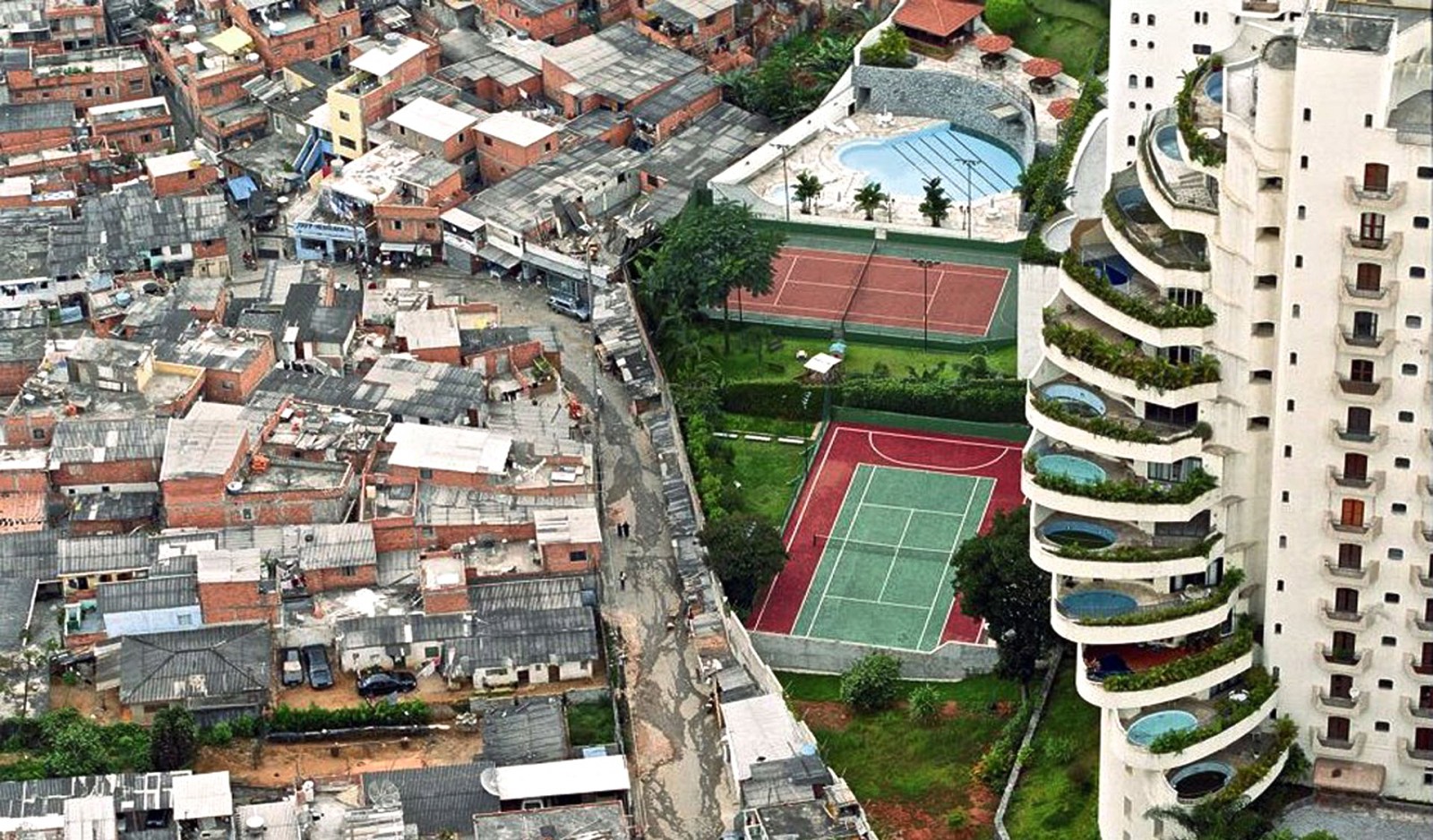

Too bad this save-the-world-complex didn’t extend to Americans themselves! Or more specifically, “the financially oppressed of our own people in America.” Now, there was progress in the “cotton gin! The spinning jenny! The sewing machine! The typewriter!” And yet, there are “millions of men and women unemployed...And no work in sight... And millions more on half-or third pay. And the dole! And suicides.” We can almost echo Dreiser word for word. We have the internet. The smartphone. The hybrid car. Viagra! But we also have “over 86 million men and women unemployed! Record number of SNAP recipients! And suicides.” The “thousands of families” evicted from their “homes,” charged with “trespassings on the public highways” and “hundreds of thousands of families are starving and disfranchised” (not unlike Steinbeck’s Joad family) are almost a dead ringer for our own foreclosures, evictions, tent cities, and makeshift homes near underpasses.Dreiser also gets it right when asserting that “in the main the majority of men and women and children in America and elsewhere weren’t any better housed, clothed, or fed than they were when I was a child.” And so it was not just for Dreiser growing up in the 1870s but for Baby Boomers and Gen Xers raised during the 1950s and 60s: a time when the working and middle classes enjoyed more generous health benefits and job security, not to mention generous grants for their sons and daughters at universities. Or a time when higher and more equitable taxes on the 1% provided better public services and schools. And not least, a time when CEOs made “only” 40 times (not 400 times) as much as their employees.

But even more provocative are his reflections on double standards for the poor and rich. Here’s some food for thought as we compare the priorities of Dreiser’s 1% and our own. For just as Depression-era elites railed against “the whole terrible wastefulness of the New Deal,” including the monies expended on the Works Progress Administration, Civilian Conservation Corps, Tennessee Valley Authority, and the Federal Theater Project, while privileging expenses for war, our own Daddy Warbucks bang on ad nauseam about “austerity” and the necessity of reducing food stamps, energy assistance, and subsidies to smaller farms while ramping up funds for the Pentagon and Homeland Security. Again, a bad case of deja-vu?

Frances A. Chiu is writing a book on Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man. A graduate of Oxford University, she teaches literature and history at The New School.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments