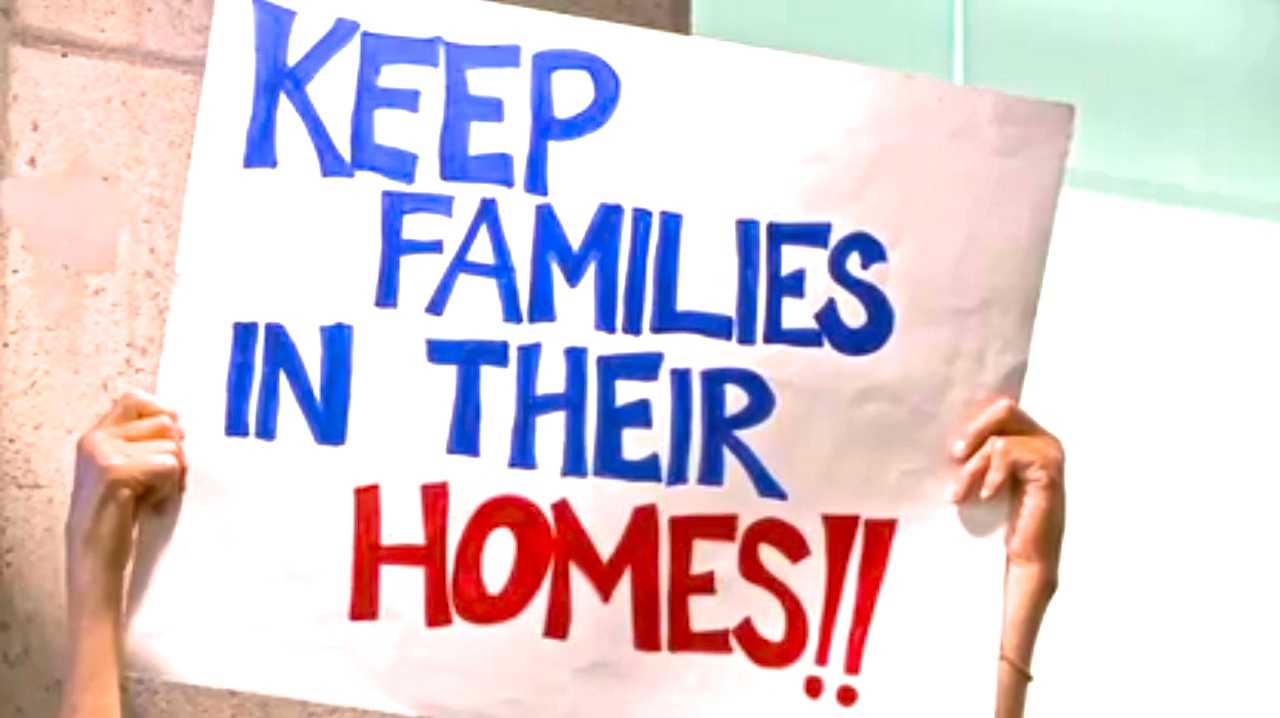

For Patti and Robert Castillo of Richmond, using eminent domain to prevent foreclosures boils down to a simple reality.

"We are living paycheck to paycheck just to pay the mortgage," Patti Castillo said. Reducing their principal through eminent domain "would help keep money in our pockets and let us stay in our house."

Their mortgage on a modest house now worth half of the $420,000 they paid for it in 2005 is among 624 home loans that the city of Richmond has threatened to seize via eminent domain in an effort to restructure them to be more affordable.

While homeowners like the Castillos welcome the idea, the banking industry loathes the idea of municipalities forcibly seizing mortgages and is vigorously fighting the effort. Last week, the American Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit against the nation's top housing regulator, seeking information on whether it's been unduly influenced by the banking industry.

The Federal Housing Finance Agency in August threatened possible legal action against localities that pursue eminent domain for mortgages, and said it might bar Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac from backing new home loans in those areas.

Now the ACLU's lawsuit seeks to uncover "the nature of (the FHFA's) relationship with the financial industry," said Linda Lye, a staff attorney at the ACLU of Northern California. "Its unusual and very aggressive stance raises potential questions of governmental integrity."

An FHFA representative declined to comment.

The eminent domain plan, in which cities would forcibly acquire mortgages at discounts, then help homeowners refinance into smaller, more affordable home loans, is at heart a form of principal reduction, Lye said.

"Principal reduction is very mainstream; there have been calls for it from entities including the secretary of the Treasury," she said. "Communities like Richmond particularly interested in principal reduction are disproportionately minority. The FHFA should be treading very carefully and looking at whether its conduct has an extra impact on communities of color. The general concern is that they would be effectively red-lined."

Banks filed lawsuits in August seeking to stop Richmond from mortgage seizures, but a federal judge dismissed them as premature. Richmond is the city furthest along in pursuing eminent domain for mortgages, but remains one City Council vote short of the supermajority needed to exert that municipal authority.

However, if Richmond or another city exercises eminent domain for mortgages, banks have signaled that they will rush to court seeking an injunction. And banks may soon have other cities to fend off.

The City Council in Newark, N.J., last week unanimously voted to study eminent domain for mortgages. That followed a November move by fellow New Jersey town Irvington to conduct a similar study.

Steven Gluckstern, founder and chairman of Mortgage Resolution Partners, the private San Francisco firm that is providing funding and advice on Richmond's eminent domain quest, said MRP does not have a formal relationship with those cities but is sharing information with them about how the plan would work.

"These efforts are bubbling up from the grass roots," he said. Several other California towns, including El Monte, Baldwin Park and Pomona (all in Los Angeles County), are considering the idea, he said.

A polarizing issue

However, both financial and political pressures continue to mount. In August, Richmond failed to find buyers when it tried to refinance some municipal bonds, an unusual snub that experts said was related to its eminent domain quest. Richmond will return to market with those bonds in January, said City Manager Bill Lindsay.

"The eminent domain program doesn't affect our credit-worthiness or ability to pay debt service, but the fact that there are headlines about it makes it more expensive for us to borrow money."

The expected cost of a higher interest rate is likely to be slightly more than $1 million over the 15-year span of the bond, he said. About a quarter of that would impact the city's general fund; the rest affects various agencies.

Richmond sold $12.1 million of annual tax revenue anticipation notes, a standard way that cities get cash flow for operating expenses, on Wall Street last week. The city's financial adviser said about $13,000 in additional interest costs might have been caused by "other factors including the headline risk associated with the mortgage risk reduction program," Lindsay said.

In moves that could presage a congressional showdown, four U.S. senators last month wrote a strongly worded letter asking the administration to oppose mortgage seizures, while 10 U.S. representatives wrote letters supporting the plan.

Eminent domain for mortgages could "scare off private capital, dry up new mortgage credit, and harm investors and taxpayers," said the opposition letter from senators Pat Toomey, R-Pa., John Boozman, R-Ark., Mark Begich, D-Alaska, and Heidi Heitkamp, D-N.D. "We are prepared to pursue a legislative solution."

The support letter raised similar points as the ACLU lawsuit, saying refusal by government agencies to insure loans changed by eminent domain would constitute discrimination.

Meanwhile, for the Castillo family, staying put carries extra urgency, as their 24-year-old son, Leon, is severely autistic. Renting was difficult, with neighbors complaining about his vocal outbursts.

They can just swing the mortgage with Robert's income as a diesel mechanic and the money Patti gets from In-Home Supportive Services for caring for Leon.

After seeing five neighbors lose their homes to foreclosure in recent years, the Castillos hope the city's plan will work for them.

"If eminent domain doesn't go through, we're not going to be able to stay here," Patti Castillo said. "We already feel the stress of raising a child with special needs. Losing our house would ruin our credit, and we'd lose our down payment. It would benefit Richmond to help keep people in their homes."

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments