Image by János Csongor Kerekes (Flickr Creative Commons), cropped from original

WHEN GAWKER MEDIA WAS SENTENCED to pay Hulk Hogan $140 million in damages for publishing his sex tape, it was seen as a victory over snarky New York media. Now, with the revelation that the lawsuit was secretly bankrolled by Silicon Valley Billionaire Peter Thiel in retaliation for an article that outed him as gay, the case has become a symbol of something else: a shadowy war on the press that’s being waged by wealthy individuals and companies, with a boost from social media.

Thiel’s provocation isn’t the oddity the media is treating it as. It’s merely the latest case of powerful interests trying to silence a journalist. Jane Mayer is a well-known investigative reporter who works for The New Yorker and is highly regarded for exposing wrongdoing and miscreant behavior. Her most recent target was the Koch brothers, only this time the target fought back. In a counterattack as sophisticated as their political finance operation, the Kochs hired Vigilant Resources International, a firm run by the former commissioner of the New York Police Department, to dig up dirt on Mayer.

“ ‘Dirt, dirt, dirt’ is what the source later told me they were digging for in my life. If they couldn’t find it, they’d create it,” Mayer wrote in her new book, Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Radical Right. And create it they did, in the form of plagiarism allegations that were shopped around to news outlets, but with so little evidence that even conservative publications turned them down.

They’re not only finding a willing audience, but also an effective way to recast the narrative, and in some cases silence the journalists they target.

There is also the case of a Wall Street stock promoter who tried to beat the press by joining it. After drawing scrutiny from journalists, he started calling himself one, launching a seemingly legitimate news site in order to publish vicious attacks on his critics in the media.

Targets of media have always sought to retaliate, but the means of fighting back has reached mass scale. An entire industry has been created, some of it underground, some of it wide open, all of it aimed at discrediting a journalist’s critical take. Companies and interest groups, often coached by aggressive PR firms, are investing in bare-knuckled strategies to give their media rebuttals more teeth and a wider audience. They launch negative online ad campaigns against particular journalists and master the art of ensuring their stories reach Google’s top rankings. In some cases, the goal is as explicit as ruining a journalist’s reputation, so that when someone types the writer’s name into a Google search, a page full of humiliating, defamatory content appears.

These techniques are well advanced from the print era’s more transparent, and contained means of challenging reporters in the past. Dull, poorly read advertorials or letters to the editor have turned into a tidal wave of tweets, fabricated stories, or entire “media watchdog” sites.

At a time when blue chip companies from Chevron and General Electric to Alibaba are staffing “newsrooms” with actual reporters—a phenomenon The Financial Times described as the “corporate invasion of news”—it makes sense that executives feel empowered to bypass the media altogether. They have a lot to lose from bad press, from stock-price declines to regulatory investigations, and much to gain by controlling it. They’re not only finding a willing audience, but also an effective way to recast the narrative, and in some cases silence the journalists they target.

THE FIRST ARTICLES ATTACKING journalists appeared in the winter of 2014 on TheBlot, a tabloid-style news site that promises the targets of media attacks a chance to fight back. The articles were all takedowns of journalists running under headlines like “Tabloid Writer Fraudster Roddy Boyd Implicated in Multiple Frauds,” and “Racist Bloomberg Reporter Dune Lawrence Duped by Stock Swindler Jon Carnes.” They featured farcical photos, like a reporter shaking hands with the devil, or a distortion of a reporter’s face, stamped with a single word: “Dumb!”

Boyd, an investigative journalist who used to work for The New York Post and founded the Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation, was unsettled by the attacks but not exactly surprised. He knew well the man behind TheBlot. He was a financier and stock promoter named Benjamin Wey, and Boyd had been covering him and his company, New York Global Group, for years. Long before Wey’s name surfaced in the Panama Papers this spring, Boyd had exposed deals Wey was transacting between US companies and shell companies in China. These transactions were designed to take a private company public as quickly as possible, without any of “the messy disclosures that serve as red flags for cautious investors,” as Boyd once wrote on his blog, The Financial Investigator. And they were not as financially sound as Wey was suggesting.

Wey had retaliated against Boyd in those days by sending threatening legal letters to The New York Post and writing disparaging things about Boyd on his company website, going so far as to falsely accuse him of having connections to organized crime. But with TheBlot, Boyd realized, Wey’s method of retaliation had become far more sophisticated.

What happened next is a vivid illustration of just how easy it is for anyone with a little capital to reinvent themselves as a so-called journalist with plenty of impact. Wey understands that the best way to get your version of the story out there is to make it appear as real as possible: to not only draft a news item, but to simulate a newsroom, hire reporters, build social media expertise, and mimic the look of a news site.

Behind the scenes at TheBlot, though, the journalists were growing wary of the stories Wey was pushing them to publish. There were splashy news items and pieces of entertainment coverage. But others had no news value at all, prompting some employees to question their employer’s motivation. “From the very beginning, I had been warned that Ben was interested in publishing pieces that targeted certain people,” says TheBlot’s former editor in chief, Alicia Lu. “Ben framed it like he was exposing corruption on Wall Street, like he was exposing people who were doing these bad things.”

When Wey handed Lu these stories, often on a flashdrive, she says she tried to push back. She says she questioned him line by line, inserting words like “reportedly” or “allegedly” wherever she could. Along with her colleague Yoni Weiss, TheBlot’s graphic designer, she wondered where some of the articles came from and who wrote them—Wey’s name was never on them. Most of all, she and Weiss wondered why they were being published.

“At first we thought Wey was having a partner from China write them, because it didn’t seem like English was the first language of whoever wrote them,” Weiss recalls. “After some quick research, it became clear these were individuals who had beef with Wey, people who had questioned his business practices.”

Wey’s lawyer, Justin Sher, speaking on Wey’s behalf, declined to comment.

Weiss and Lu weren’t the only ones who challenged Wey’s style of journalism. TheBlot’s original publisher, Neil St. Clair, quit shortly after the site launched in July 2013, as did Ned Hepburn, a staff reporter who says he resigned after Wey pressured him to write a negative piece for TheBlot about some former business associates. Lu eventually resigned in April 2014. She says the reason she stayed as long as she did, even though she knew what Wey was up to, was because she needed the job, and journalism jobs were hard to come by.

The site may be the work of a man possessed by revenge, but it’s also a spawn of the digital age, and bolstered by the First Amendment.

Bloomberg’s lawyers were also focusing their attention on Wey. Using Twitter, where he had amassed some 80K followers, Wey was accusing reporter Dune Lawrence, who covered China for Bloomberg, of committing “massive frauds.” The assault came after Lawrence published two stories that tangentially touched on Wey’s business activities. One was about short sellers and Chinese reverse mergers, the other was about one of Wey’s former clients, a Chinese animal feed company that was under investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission.

“[Dune Lawrence] was the first big one for us, because Alicia got a cease and desist letter from Bloomberg’s lawyers, which really freaked us out,” Weiss says. But rather than backing down, Weiss says Wey was enthusiastic. “Wey was like, ‘No, that means it’s working!”

He was right. Lawrence, in her recent piece for Bloomberg, “The Journalist and the Troll,” describes how overwhelming it was to type her name into Google and confront a page full of articles and images that called her incompetent and racist, derided her weight and appearance, and were laced, as she puts it, with “creepy sexual imagery.” TheBlot has since struck back by publishing fresh assaults against her—assaults that Wey shares on LinkedIn and Twitter. Despite being false and outrageous, the posts have had serious consequences for Lawrence. In her piece for Bloomberg, she describes how she and her husband were turned down for homeowners insurance because Lawrence was “too high-profile.” She also worries what future sources will think when they see the posts, especially if they’re native Chinese: “How many of them would return my calls or emails?”

Boyd also faced serious repercussions. In 2013, he launched the Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation, a nonprofit investigative outlet that focuses on business. TheBlot has lashed out at SIRF, accusing it of taking bribes from “illegal short sellers” and claiming its donors are criminals. The claims emerge from a conspiracy Wey often invokes, one that places him as the victim of a criminal network of corrupt journalists, bloggers, and racist financiers. Outlandish as these claims may be, Boyd finds himself having to answer to them whenever potential donors ask for an explanation.

Wey can seem unstoppable, even when he loses a round. In a sordid, headline-grabbing case in 2015, Wey was accused by his former assistant, Hanna Bouveng, in an $850 million lawsuit for using his power to coerce her into having sex with him and then firing her after discovering she had a boyfriend. He lost (she was originally awarded $18 million in damages on sexual harassment, retaliation, and defamation claims, now reduced to $5.6 million), but it didn’t stop TheBlot from publishing screeds against her, her lawyers, and the journalists who covered the trial. Even now, as Wey faces two civil suits for defamation, a criminal investigation by the SEC for fraud charges in a cross-border scheme to control and manipulate the stock prices of Chinese companies, and an unlawful termination suit, brought against him by Weiss, TheBlotcontinues to publish.

The site may be the work of a man possessed by revenge, but it’s also a spawn of the digital age, and bolstered by the First Amendment. Victims can sue. Journalists can write their exposés. Lu testified in court that Wey added comments under fake names to boost an article’s search results. And lawyers have objected that he is spoiling evidence by altering articles and inserting disclaimers that weren’t originally on the site. Yet TheBlot keeps churning out content, the monster child of an information landscape where publishing is cheap, speech is protected, the internet doesn’t forget (getting Google to remove defamatory content is largely a hopeless task, as Lawrence discovered), and anyone can be a media mogul.

And if anyone understands the First Amendment, it’s the media, which may explain why none of the defamation plaintiffs against Wey is a journalist.

“Journalists and media lawyers tend not to sue for defamation because they recognize there are very strong protections for free speech and it’s very hard to win a libel case, for good reason,” says David Schulz, a leading First Amendment lawyer and senior research scholar at Yale Law School. “If it were easy, the rich and the powerful would tie them up in libel cases as a way of silencing them.”

So journalists like Boyd and Lawrence are left to deal with Wey outside of court, in the realm of the open market, where it’s their word against TheBlot’s. Recently, Boyd found himself having to explain the site’s accusations to a potential donor to his foundation. He was up for a $50,000 grant, and Boyd says the donor seemed to love him. Yet, he says, the donor ended up pulling the plug, citing too much controversy instigated by Wey.

“Here’s the thing,” Boyd says. “If you fight and you go after them, if you hit them hard, they have money and they don’t go quietly.”

THE CASE OF THEBLOT is extreme, but it’s not exactly an outlier. A battle against journalists is being waged on other sites and platforms as well, where casting doubt and suspicion is often the primary weapon. The blog reportersexposed.com, for example, claims to be surfacing “dishonesty” and corruption” among reporters, even though the articles and the sources it quotes are attributed to journalists and journalism students who don’t appear to have public profiles and who can’t be reached on Twitter, Facebook, or Google. The site also questions the “sexualized manner” and romantic relationships of several well-respected investigative journalists from Newsday (one of whom is the partner of a CJR editor). Newsday’s investigative reporting team consistently produces high-impact stories exposing corruption among Long Island’s political and business elite, but it is not clear who specifically is behind Reporters Exposed.

Reporters Exposed did not respond to CJR’s email requests.

Sites like mattforney.com and returnofthekings.com proudly take on the liberal press and journalists they feel have wronged them. Forney, a freelance journalist and author himself, gives detailed instructions on how to “destroy” someone’s reputation with Google, using his treatment of a young, female reporter at ABC as an example. He also praises Roosh Valizadeh, author of returnofthekings.com, for doing “a wonderful job of tarring” a female reporter at Gawker with accusations of racism, and for his ruthless approach to “New York City Media Liberals,” especially up-and-coming journalists:

“…The blogger making $30,000 a year, trying to eke out a living in New York City, with hopes of climbing up the career ladder once it’s clear she’s not talented enough to be a real writer, is very vulnerable to being even slightly attacked. Anything that damages her future employment chances will cause her grief, pain, and a decrease in income. Twitter is a medium that is short and fleeting. Unless we can raise a huge rage army at short notice, which we can’t, there is little point using this medium to fight back. But there is a medium which lasts forever, and where numbers don’t matter as much. That medium is Google.”

Valizadeh’s site has been called hateful and misogynistic by the Southern Poverty Law Center. (If you are a female wishing to submit a question to Return of the Kings, the site’s “house rules” demand you submit your photograph first. This reporter chose not to do so. Forney did not respond to a request through his site to comment.)

In the video category, there are firms like CounterPoint Strategies, a New York public relations outfit that, in an animated short, portrays journalists as ravenous, predatory wolves who will literally tear your company apart, destroy its reputation, and cause its stock to plummet. The video’s thesis is blunt: Our current information landscape is a war zone, journalists are enemy combatants, and unprepared companies are at risk. The video, which is unlisted on YouTube and can therefore only be reached through a direct link, points to Toyota and Hewlett Packard as cautionary tales (the former faced public furor over its brake recall, the latter over allegations of spying on a journalist).

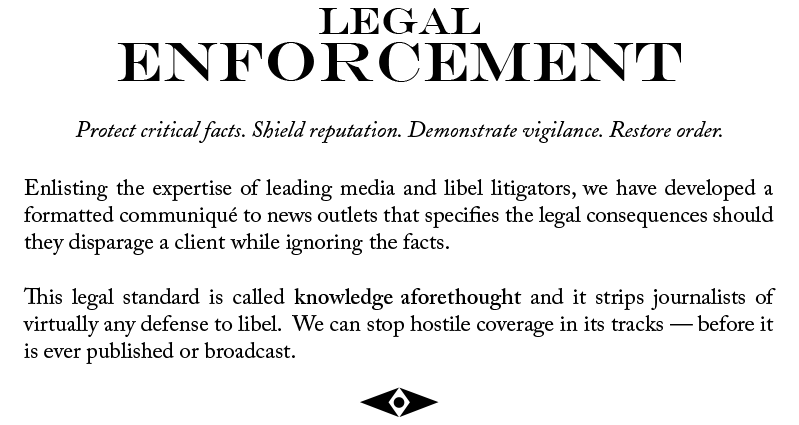

Tactics include “proprietary reconnaissance” and, as outlined in a company brochure, “counter-adversarial ads,” “search supremacy,” empowering clients to become “the primary voice about themselves,” and legal enforcement. “We can stop hostile coverage in its tracks—before it is ever published or broadcast,” the brochure reads:

The brain behind these materials is Jim McCarthy, who before founding CounterPoint gained attention while working on behalf of Augusta National Golf Club in 2001, against what he described to me as the “most vicious gender politics attacks The New York Times has ever mounted.” McCarthy helped pioneer the practice of using Google ads to target journalists and call out their supposed deceptions, usually by deftly spinning the facts surrounding their stories. Now, for better and worse, the practice has become one more tool in a marketer’s digital arsenal—one The Wall Street Journal recently called an “inexpensive amplification device” for smaller companies that can’t afford expensive PR firms.

McCarthy, in a phone interview, was emphatic that neither the video nor the brochure was used for clients or marketing purposes. He says he often speaks on crisis management at American University and uses the video as an introduction to his approach. And yet, however chilling his company’s message may be, McCarthy’s response to allegations that his tactics are aggressive will probably resonate with anyone who distrusts the media to begin with.

If all this reveals a bizarre underground battle raging against the media, it also reveals a public that is highly distrustful of journalists and ready to indulge the attacks they hear.

“We are lucky to live in a country where journalism is a protected activity. But journalists are not a protected class, and their credentials don’t confer on them any special powers to divine the truth,” says McCarthy. “So when reporters take what we do personally—coloring it as ‘bullying’ or ‘shooting the messenger’ rather than acknowledging it as a legitimate airing of the facts at issue—they are not just mistaken but revealing an arrogance that helps explain the public’s historically low regard for the press.”

This viewpoint has been embraced by corporate blogs operating under the mantle of objectivity, and even as “media watchdogs.” When the plagiarism smear against Jane Mayer came to light, the company’s blog Koch Facts had long been calling her a “liberal advocacy journalist,” guilty of “distorting the facts and misleading readers.” One of Mayer’s sources, a respected journalist in his own right who has criticized Koch Industries, was similarly disparaged on the blog of The Heartland Institute, a think tank that’s received funding from the Kochs and Exxon Mobil, among others. He was accused of being “a fake journalist,” with a photo of him shirtless above the caption: “Topless Facebook Model.”

Carey Gillam, who used to cover agriculture for Reuters and is now director of US Right to Know, an organization that receives funding from organic farmers, has received “failing grades”—an actual “F” was stamped across one of her news reports for Reuters—from Academics Review, a self-described watchdog for bad science that called for her removal from her beat. Gillam says Twitter has become an especially harsh environment for anyone who speaks out against the biotech industry.

If all this reveals a bizarre underground battle raging against the media, it also reveals a public that is highly distrustful of journalists and ready to indulge the attacks they hear. Not to mention an online environment where anyone is fair game, the loudest voice often wins, and the traditional rules of journalism don’t apply. Otherwise, the strategy wouldn’t work. For a corporate blog to assume the role of media critic is an outlandish conflict of interest. Then again, reporters don’t always get the story right, nor give companies a chance to respond. Many companies out there, whether it’s Exxon or Koch, could genuinely make a case that they’re under attack.

“Reporters have a lot of responsibility, and we don’t always use it well,” says Bethany McLean, an investigative journalist who sits on the board of SIRF. “Some of the stuff companies do, I think they view as protecting themselves against journalists who may be ill-intentioned or may simply be clueless.” For tough business journalists, company push-back is merely the cost of doing business.

What strikes McLean and others as ironic is that many of these media attack dogs engage in practices out of bounds for most professional media. Take the case of David Sassoon, publisher of InsideClimate News. After writing a critical piece about the Kochs’ involvement in Canada’s oil sands, Sassoon began to see Google and Facebook ads appearing online, calling out his “deceptions” and featuring his photo. What struck Sassoon as odd is that Koch Industries never asked for any specific corrections. It happened again this year, after ICN published a hard-hitting investigation into Exxon’s engagement with climate change. As Exxon’s blog published one rebuttal after the next, accusing Sassoon’s team of making “misstatements” and “distorting climate history,” (the company made similar accusations on Twitter, calling their claims “inaccurate” and “deliberately misleading”), the reporters awaited calls challenging the facts. But they never came.

Alan Jeffers, Exxon’s media relations manager, disputes this, saying, “We had numerous conversations both in writing and on the phone with the various reporters who have worked on the story, most of which happened prior to publication, and which did nothing to move them from their inaccurate and preconceived thesis.”

Sassoon says he’s still waiting for specific corrections. “If there was something wrong, we’d jump at correcting it. It’s our profession. It’s our integrity. So we publish 20,000 words, and they haven’t asked for a single correction.”

AS TO WHETHER THE ATTACKS WORK—that is, whether they actually cause the media to retreat—the record is mixed. In the aftermath of the Hulk Hogan suit, Gawker has filed for bankruptcy and is up for sale. There is a warning on ICN’s homepage urging readers to be “…mindful of false reports suggesting donors have sway over its editorial process, or that seek to discredit our news organization with misinformation and mischaracterization….” The warning includes a link to a recent National Review piece that suggests ICN is a mouthpiece for a public relations consultancy called Science First. It’s an accusation that has been leveled at Sassoon before, most notably when KochFacts “confronted” Reuters about publishing content by Sassoon, whom it labels an “environmental activist.” In a lengthy email exchange, published by KochFacts, Reuters defended its decision to publish Sassoon’s work.

Despite the warning on his site, Sassoon worries that prospective donors will see the National Review piece before he has a chance to meet them, that it will cast a cloud of suspicion. Given the size of his news outlet, he wonders why his critics are throwing so much weight against it. He guesses it’s because small, nonprofit news organizations such as ICN have the independence to cover tougher stories—the kinds of stories that an organization beholden to advertising dollars might be less inclined to touch.

“I mean, think about it. Our budget is a rounding error. We have 12 people. And at the time when it happened with the Kochs, we had six people. So what is it they want that they need to be so ruthless about, that they want to squash us and get rid of us?” he asks.

Investigative reporter Bethany McLean worries this dynamic is making some journalists, especially young freelancers, “pull in their horns” and go softer on companies to avoid any trouble or for fear of losing access. She recalls a time when, for reporters, having a company call you up and scream at you was considered a badge of honor.

McLean thinks the current digital landscape is ruled by a different maxim, the sense that “anything is fair game.” She has personal experience in this department. When she started reporting on Overstock.com in 2005 for Fortune magazine, she questioned, among other things, whether the company was as profitable as its CEO, Patrick Byrne, was claiming. But after McLean was attacked on the website Deep Capture, a website funded by Byrne—and accused of trading sexual favors to advance her career—she decided to stop covering him. McLean had gone up against many powerful companies in her day, most notably Enron, but as the mother of two small children, she didn’t want the risk. In that way, she says of Byrne, “he won.”

Damaris Colhoun is CJR's digital correspondent covering the media business. A reporter at large in New York, Colhoun has also written for The Believer, The New York Times, The Guardian, and Atlas Obscura. Find her on Twitter @damarisdeere.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments