Clarissa Boone, 21, stands behind a cash register at Wendy’s in New York City feeding customers for eight hours daily, six days a week, for $7.25 an hour. Because Boone can’t afford living expenses and school tuition on minimum wage, she was forced to drop out of college last semester.

Instead of sitting through lectures, she now serves up burgers and fries in a fast food restaurant without air conditioning for a paycheck that barely covers enough to pay her phone bill, rent, student loans and food.

“No one wants to spend their days making millions of dollars in profit for someone else while I get paid less than $300 every two weeks,” Boone said. “We’ve had enough of struggling to survive.”

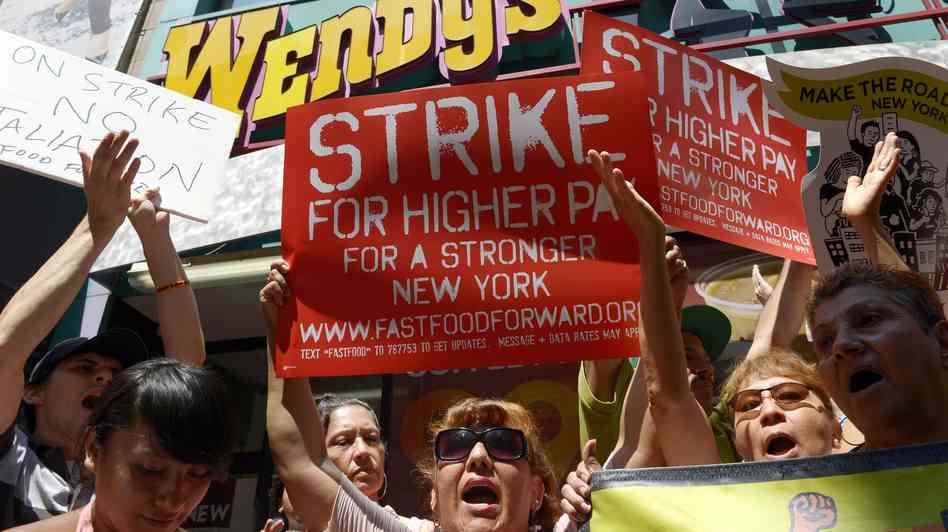

Boone and thousands of other minimum wage workers across the country on Monday began the largest fast food workers strike in the country’s history. From St. Louis to New York City, workers took to the streets to demand a $15 wage and the right to unionize.

The striking workers have organized national walkouts to shine a light on long-standing inequalities — they make a reported $170 billion annually for the industry — and their struggle to live day to day on menial wages. In New York City, fast food workers from McDonald’s, Pizza Hut and Wendy’s gathered at Union Square on Monday to rally for a living wage.

“We should be able to afford to pay for a roof over our heads and for basic living necessities,” Boone said, but “with the little pay we get, we can only afford to eat off the dollar menu.”

Chants rang out this week from the lower Manhattan square, with workers declaring, “We can’t survive on $7.25” and “No justice, no peace.” Hundreds of supporters rallied alongside striking workers and marched to a nearby McDonald’s to call out the chain’s unfair compensation to its workers.

As employees toil for an average of $11,000 annually, fast food CEOs are bringing in more than $25,000 per day, according to Fast Food Forward, the leading workers mobilization organization. While jobs are dwindling in other sectors, the fast food industry is growing rapidly each year, forcing thousands of workers into low-wage jobs. Since 2010, 300,000 new fast food jobs make up five percent of all new jobs created in the country.

Fast food employees aren’t the only ones who are supporting an increase in pay for low-wage workers. Last month, 100 economists signed a letter endorsing a $10.50 minimum wage as a form of economic stimulus and a step toward closing the economic inequality gap. The economists noted that overall business costs with the raise would only rise by 2.7 percent, equating to an increase of one nickel on the price of a Big Mac.

Along with a higher wage, workers are demanding the right to unionize in a largely non-unionized industry. Fast food workers have reported retaliation from management against their efforts to unionize co-workers, including slashing work hours and turning off air conditioning in the kitchen.

None of the country’s 200,000 fast food restaurants are unionized, leaving a vast, unorganized workforce vulnerable to exploitation and stagnant wages. Because of a high turnover rate and restaurant ownership by franchise, fast food employees are unable to unionize as easily as workers in other food service industries.

“How ridiculous is it that we have to work in a hot and humid kitchen without air conditioning during a heat wave while fast food CEOs are sitting comfortably and making millions without lifting a finger?” said James Calhoun, a cook at a McDonald’s restaurant in New York City.

Some fast food workers have expressed hope that their continued mobilization and organizing will create a sustainable, long-term movement that improves not only wages for their industry but for minimum wage workers across the country.

“I really hope raising hell about basic workers’ rights will help other workers to resist exploitation on the job,” Boone said. “Enough is enough.”

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments