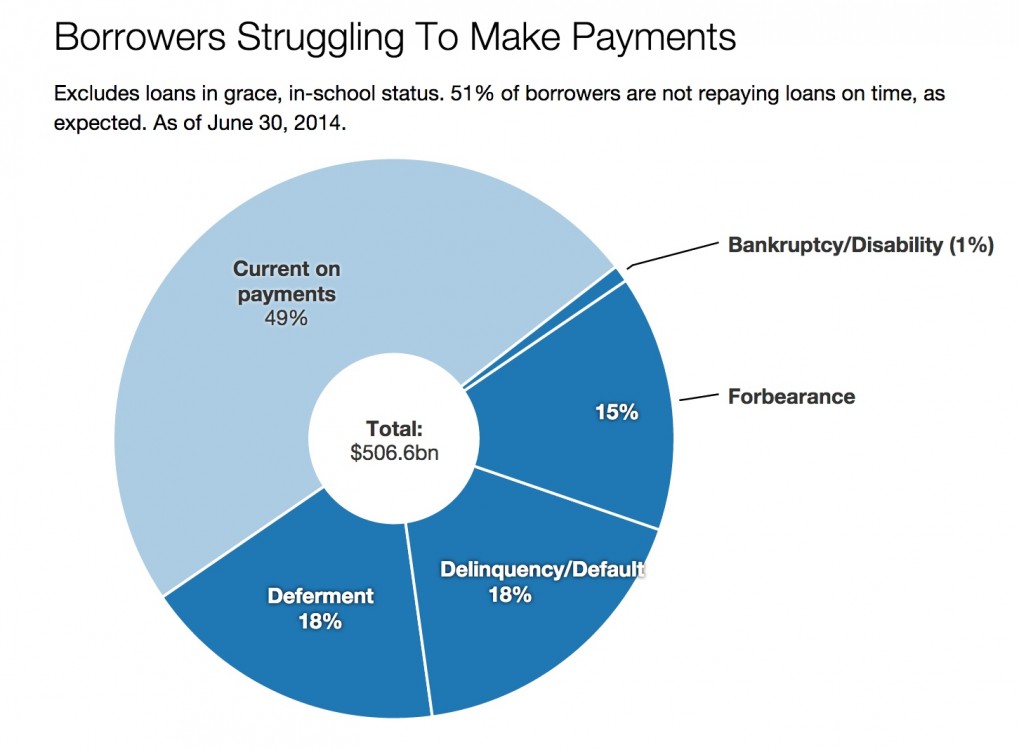

Borrowers with federal student loans, long promoted as the safest way to borrow for college, appear to be buckling under the weight of their debt, new data show.

More than half of Direct Loans, the most common type of federal student loan, aren't being repaid on time or as expected, according to figures from the U.S. Department of Education. Nearly half of the loans in repayment are in plans scheduled to take longer than 10 years. The number of loans in distress is rising.

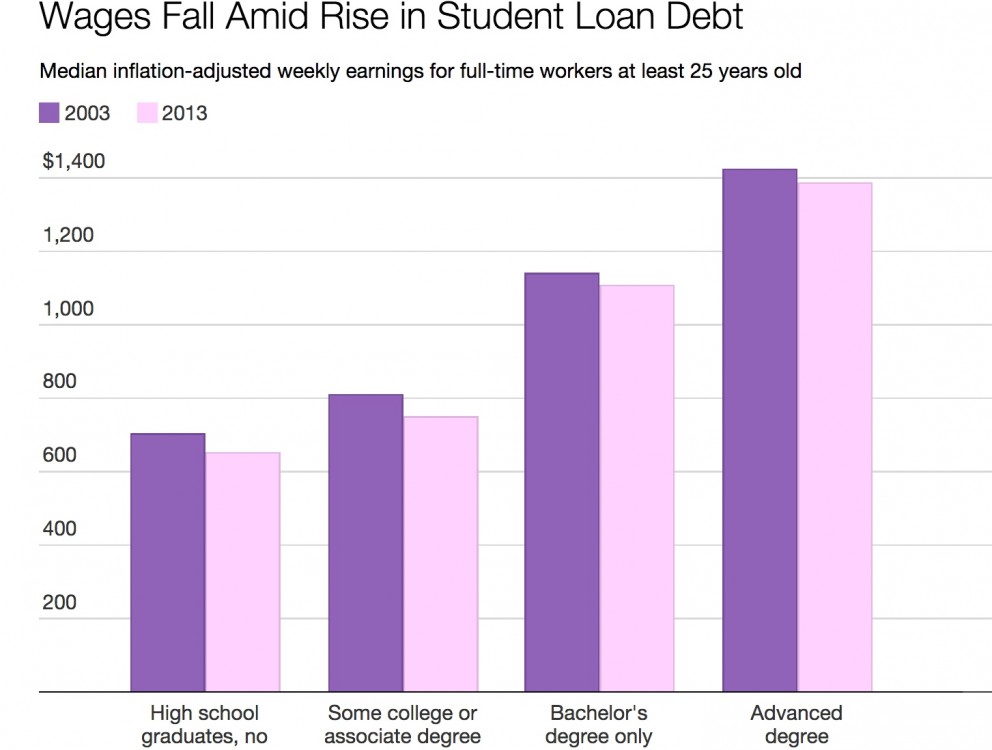

The increase in troubled loans comes as the average amount of student debt has significantly outpaced wage growth. After adjusting for inflation, the average recipient of federal student loan funds owed 28 percent more in 2013 than in 2007, according to Education Department data.

But the typical holder of a bachelor's degree working full time experienced a 0.08 percent decrease in weekly earnings during that same period. For those with advanced degrees, median wages increased just 0.02 percent, according to figures from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The Obama administration, mindful of borrowers' difficulty in repaying their federal student loans, has been promoting repayment plans that cap monthly payments relative to income. An unemployed borrower with no income, for example, could pay nothing every month, yet still be considered current on the debt.

At a December Education Department conference in Las Vegas, Brian Lanham, then an executive at student loan giant Sallie Mae, said that more than 40 percent of borrowers who enroll in so-called income-driven repayment plans have a zero monthly payment.

It's "something that's really boosted our income-driven repayment application rates," Lanham said, according to a recording of the event the department posted on YouTube. "If they're struggling," he said of borrowers, "it's an option."

The Education Department did not respond to inquiries regarding the number of borrowers enrolled in plans that require them to pay nothing to keep current on their loans. Patricia Christel, a spokeswoman for Navient, the former Sallie Mae servicing unit that has since become an independent company, did not respond to requests for comment.

Unpaid debts are typically forgiven after 20 to 25 years of repayment in income-driven plans. Some critics worry that too many borrowers are enrolling in income-linked plans, forcing taxpayers to foot the bill.

For the past few years, policymakers and regulators responsible for safeguarding the nation's economy and financial system have been warning about dangers rising student debt pose to economic growth and household balance sheets. Borrowers who devote bigger chunks of their paychecks to repaying student loans may be less likely to buy a house, stunting the housing recovery.

They also may be less likely to save for retirement, putting more strain on Social Security, or start a small business, which typically creates new jobs and boost economic activity.

The Education Department released data this month providing a much more detailed snapshot into how borrowers are coping with their federal student loans and how the government's handpicked loan companies are juggling their obligations to borrowers and taxpayers. The charts below are based on that data, as well as other sources that complement it.

A large share of borrowers are in deferment or forbearance plans, which enable borrowers to delay full monthly payments. Both are meant for borrowers experiencing some kind of financial hardship, such as unemployment, illness or a temporary inability to repay. Borrowers returning to school for advanced degrees typically receive a deferment for loans incurred as undergraduates. Deferments for up to three years also may be granted to borrowers experiencing unemployment or an inability to find full-time work.

There's little public data that details borrowers in deferment or forbearance who are postponing payments due to graduate school or military service, for example, versus financial hardship or unemployment. A 2006 Education Department study found that borrowers who used deferment or forbearance were more likely to default on their federal student loans. Deferment and forbearance also were linked to bigger loans.

"The problem is we don't know who is deferring for what reasons because the Department of Education won't release that data," said Robert Kelchen, a professor at Seton Hall University who specializes in higher education finance. "Some may be in there for what we consider good reasons -- for example, military service or the Peace Corps."

Recently, an Education Department spokeswoman said data detailing reasons for deferment weren't readily available and may take weeks to assemble, according to The Chronicle of Higher Education.

"But the Education Department should know," Kelchen said. "They should have the data. They just haven't put it together for the public to use, which is a problem."

The underlying problem, Kelchen said, is that the National Student Loan Data System, the Education Department's central database for student aid, "is by all accounts a really lousy system."

As of July 2013, the system had 28.9 billion active and historic records for 82.1 million students who combined had nearly 371 million loans and 116 million grants, according to federal procurement records.

The lack of public data has fed skepticism among borrower advocates, who claim the Education Department's loan servicers routinely place borrowers in forbearance plans rather than enrolling them in income-linked plans. Enrollment in income plans requires servicers to verify borrowers' incomes. Granting a forbearance requires little work.

In November 2012, Cynthia Battle of the Education Department told financial aid administrators that deferment and forbearance "should not be the first option," according to a copy of her presentation.

In July 2013, John Remondi, the chief executive of Navient who was then Sallie Mae's top executive, told investors that it was "very expensive work" to enroll borrowers in income-linked repayment plans.

That same month, Battle and Sue O’Flaherty of the Education Department told financial aid administrators that the department had discovered that some borrowers were on forbearance plans for extended periods, prompting the government to limit forbearances. They added that loan companies should highlight income-driven repayment plans when talking to borrowers before granting a forbearance, according to their presentation.

The message appears to have gotten through to the department's loan servicers. Among Direct Loans, which comprise nearly two-thirds of the $1.1 trillion in unpaid federal student loans, enrollment in income-linked plans has increased 68 percent over the past year.

The jump came after a June 2013 survey for the Education Department that found that 54 percent of new borrowers who were less than six months out of school didn't consider the most popular income plan -- Income-Based Repayment -- because they didn't have enough information, according to Ed Pacchetti, a department official who discussed the findings during the department's December 2013 conference in Las Vegas. A recording of his remarks is on YouTube.

Some 44 percent of surveyed borrowers who were less than six months out of school, or in "grace" status, said they had not been contacted "at all" about their loans, Pacchetti added. The previous November, Battle said most borrowers who had defaulted did not receive their full six-month grace period due to "late or inaccurate enrollment notification" by their school.

Education Department data suggest that schools and servicers have improved their outreach to borrowers.

According to Kelchen, the mere presence of income-linked repayment plans "in theory" should result in a zero delinquency and default rate. Increased enrollment in income plans should reduce the ranks of future troubled borrowers, he said.

In April, Sarah Bloom Raskin, deputy treasury secretary, questioned why some 7 million borrowers have defaulted on their federal student loans, given the availability of income-linked repayment plans.

Raskin, the Treasury Department's second-ranking official, challenged the Education Department and its loan specialists over how they handle borrowers struggling with student debt.

Education Department data suggest that while borrowers may be better informed about their options when it comes to income-linked plans, far too many aren't being properly counseled by their schools' financial aid administrators and the government's loan servicers when it comes to picking repayment plans.

The vast majority of former students entering repayment on their federal student loans in 2012 picked 10-year plans. The numbers were higher for former students from two- and four-year programs, up to 90 percent of which picked the standard 10-year plan.

Recent history indicates that many of those borrowers will be repaying their federal student loans for far longer than 10 years. With a lackluster economy, tepid wage growth and vast numbers of Americans still looking for full-time work, some federal policymakers fear current borrowers will need more time to repay their loans than previous generations.

"The concern is that money used to repay student loans are not going into building one's assets," Kelchen said. "If you're graduating at 22, it's not as much of a concern. But if you're graduating at 35, that's money that instead could be going to your retirement."

The larger fear, Kelchen said: "Will we have a generation of people who hit age 65 or 70 without any assets?"

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments