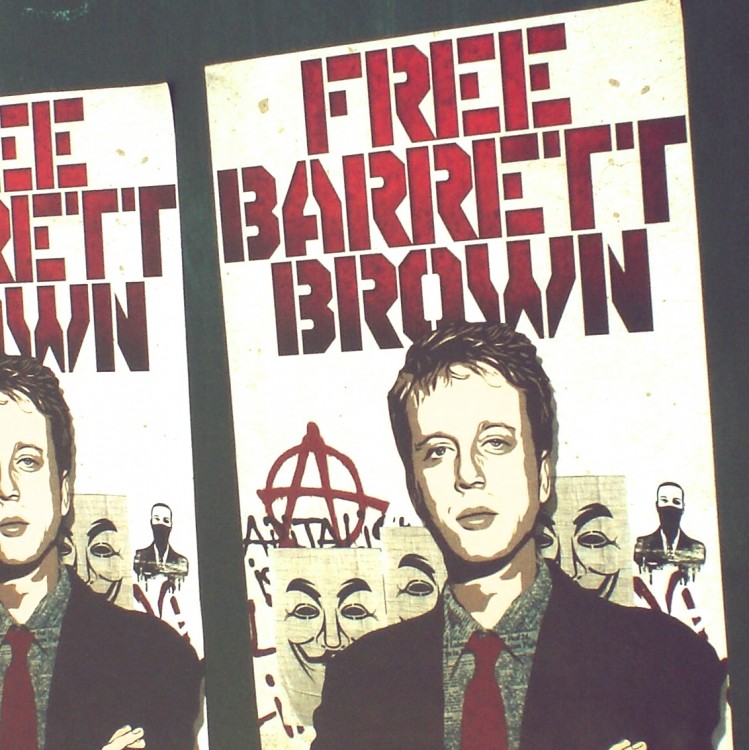

"Relevant Conduct." That's the doctrine under which journalist Barrett Brown was sentenced to 63 months in federal prison in a courtroom in Dallas, Tex., last week. Brown has already served 30 months behind bars since his 2012 arrest at the hands of federal agents. He will receive time served and is likely to spend another 30 months incarcerated.

On Thursday, Brown spoke publicly on the charges for the first time since he was arrested in a raid on his house. He had been under investigation for his alleged role in the 2011 hack of Stratfor, HB Gary and other private intelligence firms. The hack was carried out by convicted hacker Jeremy Hammond under the direction of hacker-turned-FBI informant Hector Xavier Monsegu, a.k.a. Sabu.

Brown was not a hacker but rather a journalist who hovered between the lines of journalist and hacktivist. He was reputed for his lack of hacking abilities. Instead, for most of his adult life, Barrett Brown has earned his money as a writer and journalist. Known for his biting satire pieces as well as his investigative stories, Brown's articles and blogs have been featured in publications including the Guardian, Vanity Fair and Huffington Post.

In addition to jail time, Brown was ordered to pay $890,000 in restitution fees to a number of companies involved in the hack. Critics were quick to point out the irony of Brown having to pay restitution to a company that was hacked under the direction of an FBI informant.

Judge Sam Lindsay also ruled that fifty percent of all gifts or awards will go to Stratfor and Combined Security, two of the companies involved in the hack. Upon release, Brown cannot handle credit cards, checks or bank accounts. He will be on parole for at least two years and will only be allowed to use an approved computer that will monitor all of his activity.

Throughout the hearing, the subject of what makes a journalist in the digital age was heavily discussed. In his allocution statement to the judge, Brown discussed the danger of governments defining journalism.

“The government asserts that I am not a journalist and thus unable to claim the First Amendment protections guaranteed to those engaged in information-gathering activities. Your Honor, I’ve been employed as a journalist for much of my adult life, I’ve written for dozens of magazines and newspapers, and I’m the author of two published and critically-acclaimed books of expository non-fiction. Your Honor has received letters from editors who have published my journalistic work, as well as from award-winning journalists such as Glenn Greenwald, who note that they have used that work in their own articles. If I am not a journalist, then there are many, many people out there who are also not journalists, without being aware of it, and who are thus as much at risk as I am.”

Despite Brown's having no direct proven connection to the Stratfor hack, he previously faced a century in prison for sharing a link to the leaked documents within a chat room. Hammond would later receive 10 years for that leak. The exact charges to which Brown has plead guilty include:

(1) Transmitting a threat in interstate commerce; (2) Accessory after the fact in the unauthorized access to a protected computer, and (3) Interference with the execution of a search warrant and aid and abet. Brown apologized for the threats he at one point made in a YouTube video. Judge Lindsay noted that it was this charge, however, that carried the heaviest punishment. His defense team had attempted to argue that his actions were due to stress-related withdrawal from drugs, a condition he has struggled with for much of his life.

The second charge comes from Brown offering to be a mediator for Hammond following the hack of Strafor. Brown offered the judge some background on why he made the decision to mediate for Hammond.

“With regard to the accessory after the fact charge relating to my efforts to redact sensitive emails after the Stratfor hack, I’ve explained to Your Honor that I do not want to be a hypocrite. If I criticize the government for breaking the law but then break the law myself in an effort to reveal their wrongdoing, I should expect to be punished just as I’ve called for the criminals at government-linked firms, like HBGary and Palantir, to be punished. When we start fighting crime by any means necessary, we become guilty of the same hypocrisy as law enforcement agencies throughout history that break the rules to get the villains, and so become villains themselves.”

It is this “relevant conduct” that has many journalists and advocacy groups up in arms. Judge Lindsay attempted to diffuse some of the fears when he stated, “What took place is not going to chill any First Amendment expression by journalists.” While Lindsay said “the totality of the conduct” must be considered, the way future courts interpret his ruling remains to be seen.

Barrett Brown noted the danger of the precedent. “The fact that the government has still asked you to punish me for that link is proof, if any more were needed, that those of us who advocate against secrecy are to be pursued without regard for the rule of law, or even common decency.”

Following the sentencing, Brown released the following statement filled with his usual panache:

“Good news! — The U.S. government decided today that because I did such a good job investigating the cyber-industrial complex, they’re now going to send me to investigate the prison-industrial complex. For the next 35 months, I’ll be provided with free food, clothes, and housing as I seek to expose wrondgoing by Bureau of Prisons officials and staff and otherwise report on news and culture in the world’s greatest prison system. I want to thank the Department of Justice for having put so much time and energy into advocating on my behalf; rather than holding a grudge against me for the two years of work I put into in bringing attention to a DOJ-linked campaign to harass and discredit journalists like Glenn Greenwald, the agency instead labored tirelessly to ensure that I received this very prestigious assignment. — Wish me luck!”

The chilling can already be felt. Since the verdict, journalist and security researcher Quinn Norton, the former partner of the deceased activist Aaron Swartz, announced she would “step back from security journalism” in the interest of protecting her and her family:

“I am stepping back from reporting on hacking/databreach stories, and restricting my assistance to other journalists to advice. (But please, journalists, absolutely feel free to ask me for advice!) I can’t look at the specific data another journalist has, and I can’t pass it along to a security expert, without feeling like there’s risk to the journalists I work with, the security experts, and myself," said Norton.

"I know some of my activist hacker contacts will find this cowardly of me. Many of them risk much more than this in the course of their lives, but I have two replies to this. One is that I have a family to care for including a child, and I can’t ask them to enter this murky legal territory. The other is that my causes are often not the same as the causes I write about, and I feel I best serve my causes by stepping back and highlighting this problem of law to the public.

"As the legal system drifts further out of sync with reality, the danger slowly but surely grows. When many journalists working on national and commercial cyber and security issues, and just about everyone working in security is an unindicted felon, such indictments will drift into the area of political suppression and corporate backlash. This is a process well under way in the American system.”

Norton might be on to something. Last week, the Guardian reported on a program that monitored emails to and from journalists working for media organizations in the U.S. and the U.K. In a single day, in less than 10 minutes, the British Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) collected 70,000 emails, including emails of journalists with the BBC, Reuters, the Guardian, the New York Times, the Sun, NBC, and the Washington Post. The emails were collected through GCHQ accessing the fiber-optic cables known as “the backbone of the internet.” The communications were then shared with staff on the agencies intranet.

Even more disturbing is a security assessment which listed “investigative journalists” as “a potential threat to security.” The document was shared among intelligence agencies promoting the idea that the activities of journalists were as much of a threat as foreign intelligence, hackers, and criminals. The agencies were specifically concerned with investigate journalists “who specialise in defence-related exposés either for profit or what they deem to be of the public interest.”

Security assessments released by the GCHQ also list journalists between “terrorism” and “hackers,” in some cases listing terrorists as a lower priority than investigative journalists.

This problem extends to America as well. Last summer, 38 journalists sent a letter to President Obama calling for more transparency from the White House. The groups accused the president of censorship and a “politically-driven suppression of the news.”

“Recent research has indicated the problem is getting worse throughout the nation, particularly at the federal level,” wrote David Cuillier, president of the Society of Professional Journalists, and the letter’s primary author. “Journalists are reporting that most federal agencies prohibit their employees from communicating with the press unless the bosses have public relations staffers sitting in on the conversations.”

In October 2013, the Committee to Protect Journalists released a report entitled “Leak investigations and surveillance in post-9/11 America.” The report covers the Obama Administrations attacks on the free press and implementation of surveillance measures that threaten free and independent journalism.

Most recently, USA Today's Washington bureau chief Susan Page stated that the Obama Administration was more “restrictive” and “dangerous” than any other administration in recent memory. Now, journalists around the world are watching and listening in the wake of Barrett Brown’s verdict. Although his case and the “relevant conduct” aspect is unique and only applies to the 5th circuit, it is likely the case will be used as a reference for future cases involving whistleblowers, journalists and leaked documents.

Once again, Brown offered some timely advice: “We need to restore a very rigorous tradition of civil disobedience until reasonable well-informed people are confident that the powerful are not above the law,” he said.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments