This is Part Three of an exclusive Occupy.com series analyzing the 2022 midterm elections. Click the hyperlinks to read parts one and two.

The 2022 midterms were, by almost all metrics, extremely favorable for the Democratic Party. Democrats’ US Senate majority was prolonged for at least another two years with John Fetterman’s election night victory in Pennsylvania. And with Sen. Raphael Warnock (D-Georgia) winning re-election to his first full term in the US Senate in the Dec. 6 runoff election, Democrats will now have an outright Senate majority for the first time since 2014. This is notably the first time Democratic incumbents held all contested Senate seats in an election cycle since 1943. It’s also the first time since 1992 that the once deep-red state of Georgia will be represented by two Democrats in the US Senate serving full terms.

An outright Senate majority means that committees will now no longer be evenly split along partisan lines, allowing for legislation and presidential appointments to move quicker. Conservative Democrats like Joe Manchin (D-West Virginia) and Kyrsten Sinema (D-Arizona) will now have a harder time obstructing Democratic policy priorities, as they did with President Joe Biden’s most progressive legislative proposals. And now with no power-sharing agreement necessary with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky), Senate Democrats will now be able to take on broader investigations with their subpoena powers.

Republicans controlling the US House of Representatives will undoubtedly complicate any legislation that comes from the Democratic-controlled Senate, but the GOP is now bracing for a floor fight in the Jan. 3 vote for the next Speaker of the House. House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-California) not only lacks the 218 votes needed to become speaker, but already has a challenge from Rep. Andy Biggs (R-Arizona), whom far-right activist Ali Alexander named as an accomplice in conversations with the January 6 Committee. But whomever ends up as speaker next month, it’s important to keep in mind that the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) played a role in cementing GOP control of the House of Representatives through at least January of 2025.

How the Supreme Court put its finger on the scale for the GOP

In 2019, SCOTUS issued a 5-4 ruling along partisan lines that effectively took away the ability to challenge partisan gerrymandering in the federal judiciary.

“We conclude that partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts,” Chief Justice John Roberts (R) wrote on behalf of the conservative bloc. “Federal judges have no license to reallocate political power between the two major political parties, with no plausible grant of authority in the Constitution, and no legal standards to limit and direct their decisions.”

That ruling concerned redistricting maps in both Maryland and North Carolina, where Democrats and Republicans, respectively, re-drew redistricting maps that were overly favorable to their respective party. North Carolina Republicans’ map had already been rejected in 2016 for marginalizing the state’s Black voters, but voters in the Tar Heel State were nonetheless forced to vote under the illegal maps in the 2018 midterm elections as Republicans claimed they needed more time to redraw maps to the court’s specifications. However, hard drives owned by GOP redistricting expert Dr. Thomas Hofeller showed that revised maps had already been completed more than a year before the 2018 midterms. Hofeller also inspired the Trump administration’s failed attempt to add a citizenship question to the 2020 Census, claiming to his confidants that it would be “advantageous to Republican and non-Hispanic Whites.”

Justin Levitt, an election law professor at Loyola Law School, told NPR the ruling that prevented gerrymandering challenges in federal courts put America in “Mad Max territory,” adding “there are no rules.” Justice Elena Kagan (D) also didn’t mince words in her dissent written on behalf of SCOTUS’ four liberal justices.

“Of all times to abandon the Court’s duty to declare the law, this was not the one. The practices challenged in these cases imperil our system of government,” Kagan wrote. “Part of the Court’s role in that system is to defend its foundations. None is more important than free and fair elections.”

As Levitt predicted, state-level electoral victories played a major role in the redistricting process, with legislatures now having the absolute authority to redraw maps to be most beneficial to the majority party. As was reported in part 2 of this series, Georgia’s Republican-controlled legislature took advantage of the new Congressional district the state obtained after the 2020 Census to “crack” majority-Black population centers and distribute their voters into deep-red districts in order to dilute their voting power. But a new case that SCOTUS heard this week could be the final nail in the coffin for any hopes to curb partisan gerrymandering.

The Supreme Court entertains an extremist legal theory

Now that federal courts are off-limits for legal challenges to gerrymandered maps, state-level courts are now the final battleground to defeat partisan gerrymandering in the judiciary. But the Moore v. Harper case that was orally argued in SCOTUS chambers on Dec. 7 could even take that avenue away if plaintiffs are successful.

As legal scholar Chris Geidner wrote for his newsletter, Law Dork, the theory at the center of Moore v. Harper is the “independent state legislature” theory. Its adherents believe that since the Constitution vaguely states that “[t]he Times, Places, and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof,” challenges to those rules can’t be heard in state-level courts. Geidner characterized this theory as “nonsense.”

That same theory was at the center of former President Donald Trump’s arguments after his loss in the 2020 presidential election that state legislatures should be free to appoint their own electors who can vote against the will of their state’s voters if they so choose. The Supreme Court declined to hear that argument in December of 2020, meaning Moore v. Harper is the first time the Roberts court has weighed in on the independent state legislature theory. David Thompson, one of the lead petitioners in Moore, even said during oral arguments that he believed Arizona’s legal challenge of the 2020 election that helped inspire the January 6 insurrection was “correct.”

The independent state legislature theory is even scoffed at by some conservatives. J. Michael Luttig (R) – a George H.W. Bush-appointed judge who once sat on the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit – wrote in The Atlantic that the theory was “antithetical to the Framers intent, and to the text, fundamental design, and architecture of the Constitution.”

“That as many as six justices on the Supreme Court have flirted with the independent-state-legislature theory over the past 20 years is baffling. There is literally no support in the Constitution, the pre-ratification debates, or the history from the time of our nation’s founding or the Constitution’s framing for a theory of an independent state legislature that would foreclose state judicial review of state legislatures’ redistricting decisions. Indeed, there is overwhelming evidence that the Constitution contemplates and provides for such judicial review.”

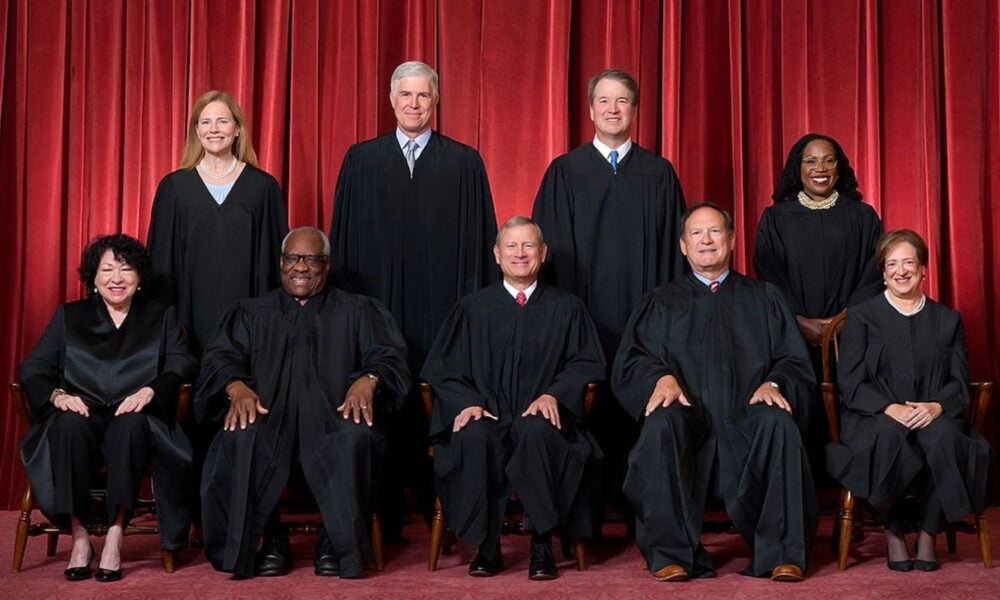

While livetweeting Moore v. Harper’s oral arguments, Geidner wrote that Justices Samuel Alito (R), Neil Gorsuch (R), and Clarence Thomas (R) all seemed friendly to the independent state legislature theory, with Gorsuch as a particularly vocal champion. But thorough questioning by Justices Amy Coney Barrett (R) and Brett Kavanaugh (R) led Geidner to conclude that there may be enough Republican SCOTUS appointees to give the three Democratic appointees a 5-4 or even a 6-1-2 decision that would crush the independent state legislature theory.

However Moore v. Harper is decided, the underlying fact remains that allowing politicians to choose their voters is antithetical to democracy. Organizing for states to have nonpartisan redistricting commissions free from the influence of elected officials is the only sure way to ensure that the redistricting process will fairly represent voters in the future.

Carl Gibson is an independent journalist whose work has been published in CNN, The Guardian, The Washington Post, Barron’s, Business Insider, The Independent, and NPR, among others.