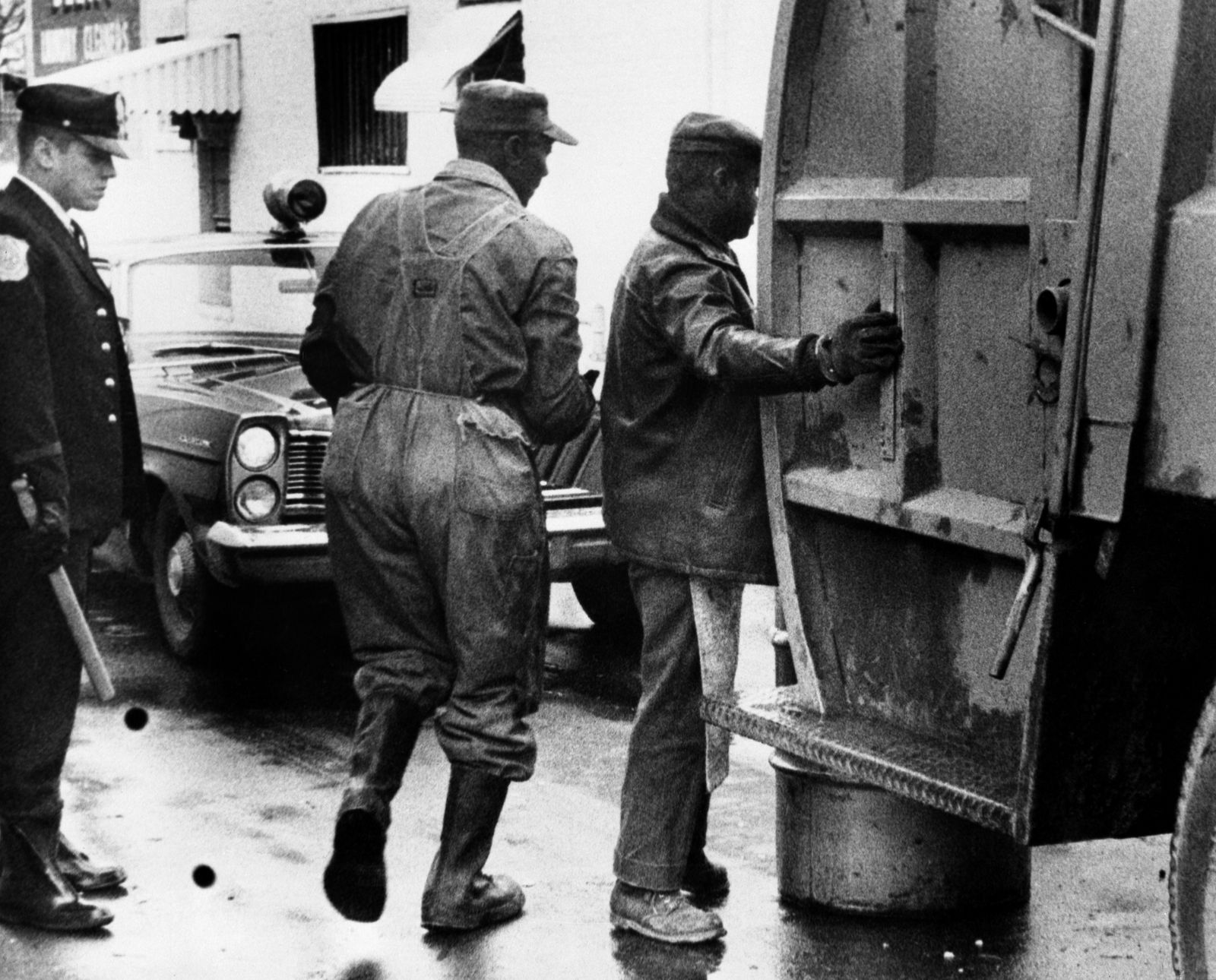

On February 1, 1968, two Memphis sanitation workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were crushed to death when the trash compression mechanism in their truck malfunctioned. Their deaths served as further evidence of the dangerous working conditions sanitation workers in the city had been dealing with for more than a decade.

Soon after, some 1,300 Memphis sanitation workers walked off the job in protest of a volatile mix of dangerous working conditions, poor benefits, inadequate pay, and an inability to form a union recognized by the city.

The strike began on February 12, 1968, and lasted until April, drawing national attention and the support of a number of civil rights figures, including Martin Luther King Jr. He saw the Memphis strike and the workers’ demand for union rights as embodying the goals and values of his fledgling Poor People’s Campaign, a movement that sought to bring a multiracial coalition of religious leaders, workers, and the poor together to fight poverty in a way that intentionally centered the voices of the marginalized.

It was the strike that would bring King to Memphis several times that spring, including on April 4, the fateful day of his assassination at the Lorraine Motel. Shortly after King’s assassination, the striking workers gained union recognition and some benefits, overcoming Memphis Mayor Henry Loeb’s longstanding resistance to reaching an agreement.

Fifty years later, a new generation of activists, religious leaders, and civil rights groups aim to carry forward the legacy of the 1968 sanitation strike. Their efforts began Monday, as fast-food workers affiliated with the Fight for $15 movement, which organizes around raising the minimum wage, gathered in Memphis and dozens of other cities, joining a new iteration of the Poor People’s Campaign to fight for racial and economic justice, union rights, and a moral revival aimed at lifting up the needs of the working poor.

The actions will culminate in a six-week period of civil disobedience and protest in a number of states this year, eventually fulfilling King’s original goal of bringing the needs of poor people directly to the nation’s capital.

“In Memphis, folks rose up and said, ‘We demand dignity, we demand the right to organize, we demand respect, and we are going to organize to get that respect,” said Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis, a co-chair of the new Poor People’s Campaign alongside North Carolina Moral Mondays organizer Rev. Dr. William Barber.

“And that compelled people like Dr. King,” Theoharis said, “to see the natural connection between low-wage workers who are fighting racism, fighting the lack of dignity, and fighting economic exploitation and others who are saying we want to be a part of something bigger and we are prepared to fight for our rights and the rights of everyone around us.”

The Memphis strike was about more than its value to the broader civil rights movement, the labor struggle, or even its connection to King’s final campaign.

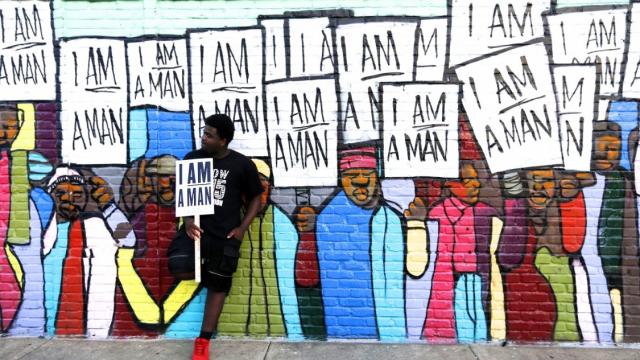

It was a chance for the city’s black sanitation workers, many of whom had been forced to work long hours in sweltering heat or intense cold with little equipment, lacking benefits, and dismal pay, to assert their rights and claim their dignity (as the strike continued, workers converged on the statement “I Am a Man” as a reflection of their rights and values).

The strike was a reminder of the power of people fighting for better conditions for themselves and their families. Fifty years later, their work has sparked a change that workers today are attempting to emulate.

In 1968 Memphis, “Sanitation Workers Existed in a Netherworld Between the Plantation and the Modern Urban Economy”

The story of the Memphis strike is often woefully abbreviated. In most tellings, it starts with the deaths of Cole and Walker in February 1968, picks up with the involvement of King and his Poor People’s Campaign in March 1968, and trails off after King’s assassination.

These accounts ignore the history of labor, particularly black labor in Memphis and other Southern cities like it. In many of these cities, blacks seeking opportunities in the South beyond sharecropping found themselves in low-wage positions reserved for black employees. Unionizing in many of these jobs was difficult, and even when unionizing did occur, racism within many unions kept blacks and whites from serving as truly collaborative partners.

Through a concerted effort that preyed upon black and white tensions, union busting, and offering low wages, in Memphis, the “income of unskilled workers, both white and black, average[d] less than half of the average in the rest of the country,” according to Michael Honey, a labor and civil rights historian at the University of Washington Tacoma, whose book, Going Down Jericho Road: The Memphis Strike, Martin Luther King’s Last Campaign, captures the history of the strike.

The result was that people of all races, but especially African Americans, found themselves doing intensive labor for little pay. And in Memphis, there was practically no job as demanding as that of a sanitation worker.

“We went through terrible ordeals, having to work in the cold; we didn’t have sufficient working equipment, didn’t have water to drink,” said Rev. Cleophus Smith, a surviving participant in the 1968 strike who still works in sanitation for the city. “No place to wash our hands. When we went to lunch, we didn’t have anywhere to sit.”

In a phone interview with Vox, Smith, who first started working for the Memphis Department of Public Works in 1967, explained just how grueling the work could be.

Sanitation workers would often need to go into people’s backyards and take trash out of a large 50-gallon drum, placing it in a washtub to more easily bring garbage to the truck. A single drum filled to the brim could require multiple trips to remove all the trash.

“To make the load lighter, we had taken some railroad spikes and punched holes in the bottom of the tub, causing water [collected in the tub, usually from rain soaking the trash] to run out,” Smith said. “We used to put the tubs on our shoulder with the juice running out down on our clothes. At the end of the day, we wasn’t able to get on a streetcar bus because of the stench.”

Workers were often forced to walk home, covered in trash, maggots, and other debris. The city did not provide uniforms, forcing them to wear their own clothes. Things were worse when it rained — not only could a sudden storm catch a man unprepared for working in the weather, but rainy days often saw black workers sent home without pay.

Despite the necessity of their work, sanitation workers were considered the bottom of the Memphis economy, earning just $1.65 an hour (roughly 5 cents more than the federal minimum wage at the time) by 1968.

If white bosses in Memphis were seen as leading the remaining vestiges of plantations in Memphis, then many black low-income workers were seen as working in the vestiges of slavery. As Honey put it in his book, “sanitation workers existed in a netherworld between the plantation and the modern urban economy.”

Those conditions had spurred previous efforts to organize sanitation workers. At the time, workers in the South were far less unionized than their Northern counterparts, and black workers were perhaps the least unionized of these groups. In the years prior to the 1968 strike, black sanitation workers in Memphis had sought to learn more about unionizing only to be fired after attending labor meetings, and a previous effort at a strike in 1966 was curtailed by strikebreakers.

The imbalance of power left men with little recourse should they be injured on the job, something seen by the widows of Cole and Walker firsthand when they received scant compensation or support from the city in the wake of their husbands’ deaths.

Frustration over these conditions, built over decades and aggravated by the truck accident, led the workers to strike, demanding better pay and benefits, as well as a union to advocate for their interests. Many white Memphians hoped the effort would fail, with city officials framing the strike as an illegal threat to public safety.

In its earlier days, union representatives, many of them from the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, sought to frame the strike in purely labor terms, arguing that the city needed to recognize its workers’ calls for a union if it ever hoped to end the strike. But local black ministers and civil rights leaders also saw the workers’ plight as a racial one; their struggle was rooted in the ongoing mistreatment of black Americans in Memphis.

For King, who in 1961 had argued that the “two most dynamic and cohesive liberal forces in the country are the labor movement and the Negro freedom movement,” the issues were deeply connected. He saw his Poor People’s Campaign as bridging the connections between race and class, creating an agenda that would focus on the poor.

It is an agenda that many poor workers say is still needed today.

50 Years Later, a New Campaign to Uplift the Poor

When workers in Memphis marched on Monday from Clayborn Temple to Memphis City Hall — the same route that the Memphis sanitation strikers walked 50 years ago — carrying signs that say “I AM a Man,” “I AM a Woman,” and “I AM Worth More,” in recognition of the rallying cry of the Memphis strike, they were seeking to honor the work done half a century ago.

“In Memphis, we consider them pioneers,” said Ashley Cathey, a Memphis-based fast-food worker and Fight for $15 organizer, of the 1968 sanitation workers. “Their starting the strike in Memphis made other workers want to stand up and speak out for themselves.”

But striking workers are also hoping to draw attention to the fact that in many ways, things have not changed.

“We’re fighting for the exact same thing sanitation workers fought for 50 years ago,” Frances Holmes, a St. Louis McDonald’s worker, said in a statement. “We can’t end poverty or stamp out racism in this country unless everyone can earn a wage they can live on and has the right to organize. And we will keep on striking, protesting, and even risking arrest until that dream becomes a reality.”

For Terrence Wise, a Fight for $15 organizer from Kansas City, Missouri, who is also working on the new Poor People’s Campaign, the 1968 strike serves as an example of the importance of people organizing and fighting for their own needs.

Wise has been working in fast food for more than 20 years, but he and his wife, a home health aide, still struggle to make ends meet and provide for their three daughters. Despite his years of experience, Wise tells me he still doesn’t make more than $10 an hour. He joined the Fight for $15 not only because he believes that workers should make a living wage, but also because he wants workers in the industry to unionize.

“When we talk about poor people, people forget to put the adjective ‘working poor’ in front of it,” Wise said. “ And I think that is something that Fight for $15 has been working to highlight and you’ll see it on the Poor People’s Campaign as well. Most of the poor people that we are talking about are workers, and that is where we have to see the common thread in both movements — that we are all working Americans; we all face this racial and economic inequality together.”

As Aaron Morrison noted Monday in a story about the Memphis strike for Mic, the economic conditions that existed in the 1960s are still uncomfortably close to those of today.

“Nearly 50 years since the late civil rights icon’s assassination, persistent gaps in livelihoods between whites and people of color means that King’s campaign remains unfinished business,” Morrison writes. He points to a Pew Research Center analysis from 1967 that found that when adjusted to 2014 dollars, the median black household income was $24,700, compared to a median white household income of $44,700.

In 2014, the median black household income was roughly $43,300, compared to a median income of about $71,300 for whites.

Theoharis, the Poor People’s Campaign co-chair, notes that income isn’t the only place where these gaps have persisted. Other issues that heavily affect communities of color, such as mass incarceration and police violence, have only become more skewed with time. “We’ve seen all of the evils that Dr. King was talking about 50 years ago [still] kind of rearing their heads,” she said.

Smith, the surviving Memphis sanitation worker, also says he is still fighting the battles waged in Memphis in 1968. When the strike ended that April with union recognition for the sanitation workers, the city offered them a choice to either use Social Security for retirement or join Memphis’s pension plan.

The workers chose Social Security, only to then discover that the funds would be far less than what they would have received from the pensions. The federal government would not allow the workers to switch back, creating a significant gap in the retirement funds available by the sanitation workers when compared to other city employees. Smith says that’s one reason why being a sanitation worker in the city is still difficult.

In the summer of 2017, the city of Memphis agreed to offer additional compensation to the surviving sanitation workers to help make up the difference, giving each of the 14 a $50,000 tax-free grant to help cover the costs of their retirements. It was welcome relief for Smith. On April 15, he’ll mark 51 years of working for the sanitation department. The next day, on April 16, will be the 50th anniversary of the end of the Memphis strike.

As April approaches, Smith says that he hopes to see more workers across industries and racial lines come together to advocate for change. “Let’s get together and work together, pull together and try to make the workforce better,“ he says. “We can’t do it if we are clawing at each other.”

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments