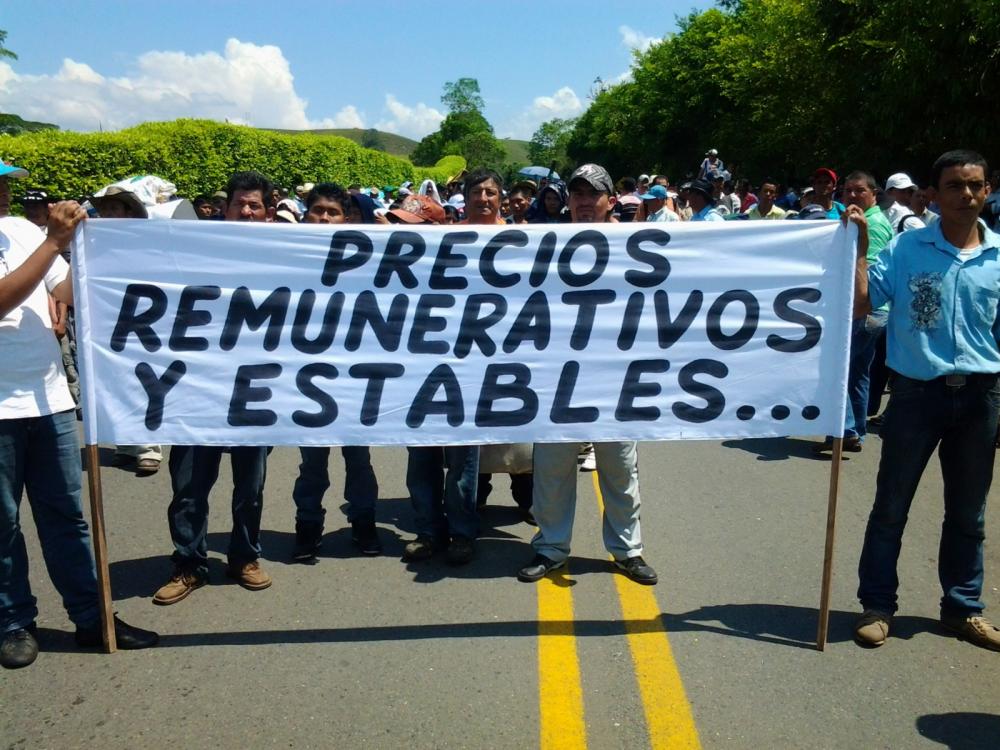

MEDELLIN, Colombia – Colombia’s agrarian workers made headlines across the world last month when they brought their country to its knees with coordinated strike actions. At times, the battle turned violent and roadblocks prevented police and ambulances from reaching their destination. But due to a lack of coverage in the United States, many are unaware that the difficulties actually stem from a controversial free trade agreement with Washington.

The reasons for the strikes are manifold. Several different groups, including coffee farmers, truckers and miners, joined up to express their grievances. It is impossible to pin down one sole cause. However, it would appear a huge part of the problem derives not only from Colombia’s relationship with the United States of America in general – but with the specific agreement entered into last year, in which the Colombian government privatized seeds pushing farmers to the brink.

At one point, authorities went so far as to seize 70 tons of rice from the country's own cultivators and dump them in a landfill. The story was exposed by a Spanish-language documentary made by university student Victoria Solano.

But Colombia does not suffer the agricultural conflict alone. Farmers from Mexico, Peru and Chile are also at risk from similar agreements with the U.S. The fact is that while the treaties benefit large corporations and the United States as a whole, local peasant populations suffer immeasurably.

In Colombia specifically, farmers argue that the lack of government subsidies and the excessive price of fertilizers make it impossible to compete with foreign products. Due to regional monopolies, these items cost 25-45 percent more here than in other countries.

Obama spoke recently of the United States’ hard-working agricultural industry, saying, “If the playing fields are level, America will always win.” But when a poorer country is forced to destroy much of its own crop in order to adhere to a nation-to-nation "deal," it would appear those playing fields are more level for the U.S. than anyone else.

During the protests, Colombia’s President Juan Manuel Santos did not help matters. He constantly popped up in the media to taunt and belittle the strikers. He tried the customary line of blaming guerrillas and rebels in the mountains. The president also made startling claims that only "10 or 15 people" were involved in the strikes and that the situation was "under control" when clearly it was not. He said: “This so-called agrarian strike does not exist.”

The instability was visible to anyone who wished to see it. Roadblocks brought the South American nation to a halt. Food prices doubled since truckers were too afraid to transport goods. And even tourists felt the effects as they were unable to move freely from city to city; the north-south freeway was completely cut off, freezing travel from Popayan and Cali to Bogota and Medellin.

According to official police reports, there were five deaths and hundreds of injuries as a direct result of the conflicts in the countryside. There could be many more unknown fatalities. Students joined the fight as well, with bombs going off in the universities across the country. Occupy.com spoke with Norwegian student Julia Bårdsen at the Universidad de Antioquia. She witnessed multiple explosions.

“Every week, they let off bombs on campus to show the government they were not happy with the farming situation. It became the norm," said Bårdsen.

“The first time was terrifying. At first, I heard explosions and saw a lot of smoke coming out of a classroom. Suddenly, police in SWAT uniforms turned up and started shooting wildly into the smoke. I got out of there pretty fast.”

Perhaps this was President Santos’ idea of "under control," though in time he too appeared ready to face up to the crisis engulfing the country. Despite claims that he would never negotiate, the government is now finally in talks with union leaders. The protests are over and center-right Santos’ approval rating has taken a dramatic fall, according to a recent Gallup poll.

Despite its huge strides in recent years, Colombia continues to suffer from a huge disparity in wealth distribution. The country has failed to invest in small-scale trade activities, and farmers occupy first place in a long list of neglected people who make the country tick – from miners to teachers to truckers. Now, with farming particularly difficult and expensive, Colombia's decision to open its doors to international competition from giant U.S. corporations only compounds the people's hardship.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments