If money amplifies the voices of wealthy Americans in politics, Seattle is trying something that aims to give low-income and middle-class voters a signal boost.

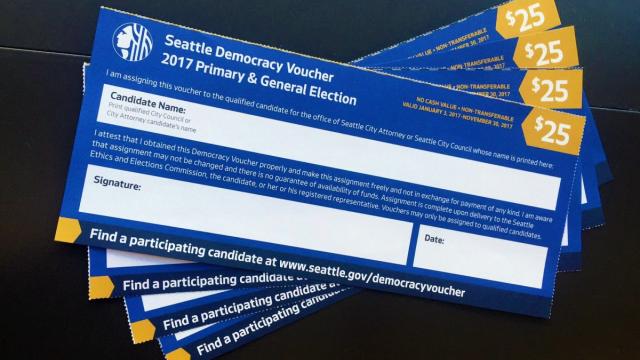

The city’s new “Democracy Voucher” program, the first of its kind in the U.S., provides every eligible Seattle resident with $100 in taxpayer-funded vouchers to donate to the candidates of their choice. The goal is to incentivize candidates to take heed of a broad range of residents – homeless people, minimum-wage workers, seniors on fixed incomes – as well as the big-dollar donors who often dictate the political conversation.

This August’s primary is the trial run for the program. But before Seattle can crow about having re-enfranchised long-overlooked voters, it must contend with conservative opposition.

The experiment comes at a time of seemingly new possibilities for campaign financing. Bernie Sanders demonstrated that small donors can float a campaign, with 99% of his donations coming from individual donors, 59% of which were considered small donations.

Last fall, South Dakota voters approved a program similar to Seattle’s, joining more than a dozen other states with some form of public financing, usually a matching fund for small campaign donations. Cities such as Portland, Oregon, and Berkeley, California, also followed the public-financing trend last year.

In Seattle, “if we had a concerted effort to register, educate, and organize renters and people who are homeless as a political force, our city politics would look rather different than they currently do,” said Alison Eisinger of the Seattle/King County Coalition on Homelessness, which works to register homeless voters, among other advocacy efforts.

The democracy voucher program was created by a voter-approved ballot measure in November 2015 and is funded by a 10-year, $30m property tax levy. Registered voters are automatically sent the vouchers. Those who are not registered and those without a permanent address – such as homeless people – can apply by mail or in person with a city commission.

Seattle candidates are not required to participate in the voucher program. But Jon Grant, a leftist city council candidate who previously led the Tenants Union of Washington, has made the vouchers a centerpiece of his campaign. He has pushed to collect vouchers from over 1,000 people, including those living in several homeless encampments.

Of the $145,933 in donations that Grant reported on the most recent campaign disclosure form, $128,800 is from vouchers.

“I took a pledge not to accept any money from corporations and developers,” Grant said. “I wanted to show that democracy vouchers can support grassroots campaigns that want to address systemic issues like homelessness.”

As part of that effort, Grant spent several months organizing in three unsanctioned homeless encampments, helping to set up a communal tent in one encampment, and registering people to vote and receive vouchers. “We wanted to work with those residents to assist them to stabilize their living situation and shine some light on how the city was handling the situation,” he said. “We started building trust and organizing there and wanted to educate people that they had access to democracy vouchers.”

Grant’s campaign received a few vouchers from them, but the city cleared the encampments before the campaign’s organizing efforts truly gained steam. Though they are gone, Grant is still working to engage homeless people around the city.

Yet at the same time that Grant’s campaign is being cited as a democracy-voucher success, lawyers are presenting it as evidence in a bid to kill the program.

Libertarian law firm Pacific Legal Foundation is representing two Seattle homeowners in their lawsuit against the city. They allege that democracy vouchers violate their first amendment rights because their taxes are funding candidates they oppose.

PLF lawyer Ethan Blevins wrote in an email that Grant’s campaign highlights “the injustice done to property owners who oppose his candidacy. … Mr Grant’s views on rental housing clash with the interests of landlords – yet these are the very people who have unwillingly fronted most of the money for his campaign.”

University of Washington constitutional law professor Hugh Spitzer told the Stranger that some of their legal reasoning “doesn’t make any sense at all” and suggests a misunderstanding of how property taxes work.

Naturally, Grant agrees. “The voucher program is very much in line with the values of most Seattle voters. This lawsuit is the death rattle of many corporate interests who were hoping to keep their hold on city hall.”

Lawsuit aside, prospects for the vouchers are murky.

Vouchers alone will not change the political status quo, said Devin Silvernail, executive director of homeless advocacy organization Be:Seattle, which recently launched an effort to help homeless people register to vote when they check into shelters.

“There are a lot of folks elected to office who, to be frank, don’t give a shit about people who are having a hard time,” he said. Still, putting vouchers in homeless peoples’ hands “ will be really useful as the start of a way for them to get their perspective known by elected officials.”

Proponents must also combat feelings concerning the futility of voting.

“Our little voucher would be so small compared to corporate America’s donations,” said Soukaynah, a woman in her late 50s who was part of a knitting circle on Wednesday at the Mary’s Place day center for homeless women in downtown Seattle.

Bobby Gene, a 75-year-old who also declined to give her last name, was homeless until she was recently placed in a low-income housing complex for seniors. She received democracy vouchers but doesn’t plan to use them.

“Maybe they would do some good, but politicians don’t want to listen to us,” she said. Candidates, she suggested, as good as vanish once they attain office.

“We only see them when it’s time to vote, when they’re kissing babies and shaking hands. Then we never hear from them.”

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments