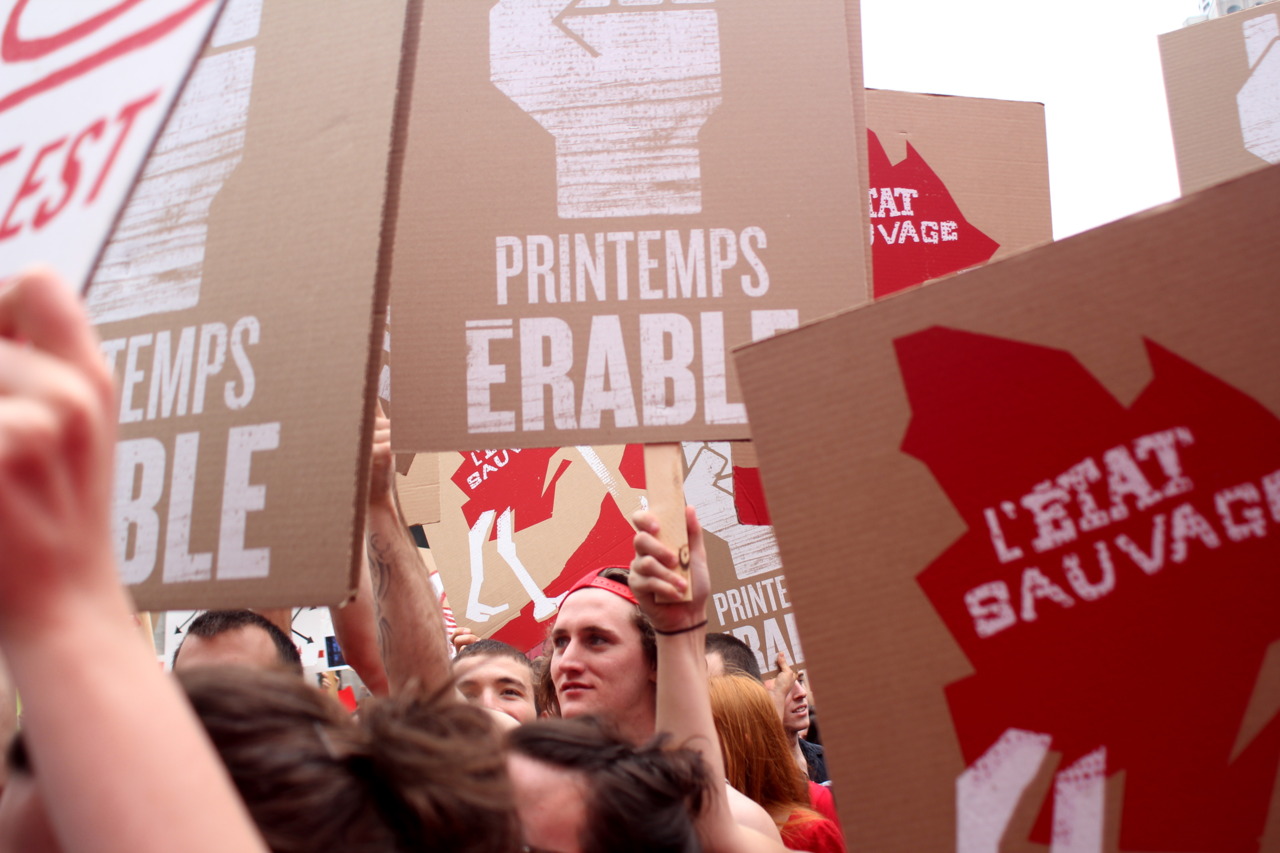

Last year, the Maple Spring raised some hopes for the mobilization and victory potential of social movements. In hindsight, one year later, one can draw some conclusions about the legacy of the uprising — and how it relates in certain ways to the Occupy movement that preceded it.

The widely admired mobilization of Quebec students lasted for about six months. About 300,000 students took part, according to Renaud Poirier St-Pierre, the former spokesperson of the coalition of student organizations. Then, due to elections and the perceived exhaustion of the movement, things returned to "normal."

The Quebec Party promised before the elections to freeze student fees to the amount of $325 Canadian dollars per year over five years, but the party subsequently changed that figure to $245 per year over seven years, making it a rather short term success. The new government headed by Pauline Marois shifted the financial burden to universities by cutting the provincial budget for higher education by $124 million. For McGill University, this implies $43 million less funding for its operations. In February 2013, the provincial government announced a student fee increase of $70 annually for an indefinite period.

The protests, by then, had demobilized. One the one hand, the strike exhausted students who needed to catch up again with a fast paced curriculum. But there were further personal consequences as well, such as fines for participating in the protests. Introduced by former government bylaws made some demonstrations illegal and in the winter 2013 this regulation was used to prevent mobilization.

In more than 700 demonstrations that took place in Quebec between February and September of 2012, 1,868 arrests took place. This past winter, some demonstrations gathered around a thousand people, and the police became more offensive. In just three demonstrations in March, they recorded some 650 arrests. The average fine for each was $634. On March 22,the anniversary of the students' uprising, police prevented a demonstration by arresting 250 people, including passers-by.

The struggle continues, but not on the streets. The activists have tried policemen for brutality, but generally the courts have ruled in favor of the police. To pool their resources, activists have turned to generating a registry of policemen on facebook and dropbox in an attempt to force a collective trial.

How it All Got Started

Mobilization of students in Quebec did not develop spontaneously, but due to the long preparations and resources that stood behind them. Renaud Poirier St-Pierre, the former spokesperson of CLASSE, a broader coalition of student unions, indicated that the preparations lasted for two years. In the beginning, there was little interest in collective action among students, which brought organizers to realize that investing in a renewal of the student movement needed to happen first.

They started with a petition. The goal was to make students aware of the fee hikes that were looming. Some symbolic actions helped assess potential for organizing more radical protests. The organizers analyzed which university campuses were more probable to be interested in strike actions, and on those campuses, voting on the strike was organized earlier to encourage other campuses.

Initial student protests were followed by further mobilization. Neighborhood assemblies (Assemblées populaires autonomes de quartier, or APAQs) were established in Montréal’s districts. The main idea was to develop direct democracy at the district level and support student protests. One of the organizers from the poor, working class district of Pointe-St-Charles (PSC) was Nicolas van Caloen, who had known and worked with people engaged in similar structures in Argentina in 2001. Van Caloen gave two pieces of advice on the organization of assemblies.

First, they should be conceived as stable and permanent structures from the very beginning. Second, they should define as their aim a larger project, instead of being only a response to current events taking place. In PSC, organizers were inspired by a libertarian and anti-authoritarian view of society. Organizers, said van Caloen, tried to avoid a concentration of power from the very beginning.

After two initial meetings, organizers introduced a rotation of tasks that included writing summaries of the meetings, organizing follow-up meetings, facilitating the assemblies, and combining people who had experience with others who had less so that the teaching could expand quickly and effectively. The aim of the organizers was not to achieve specific goals per se, but to create a space where citizens could meet, present their own views or proposals, and make decisions about them. The process itself — and the capacity to make decisions collectively — were considered an accomplishment of a libertarian goal.

Later, as people began to drop away from the movement, the originally heterogeneous group became more composed of anarchists. The fall in participation was continuous and took place all over Montréal; for example, in Rosemont-Petite-Patrie, where numbers dropped from 200 to 20 and in Plateau Mont-Royal, where they fell from 50 to 6. Recalling the experience in the PSC district, Anna Kruzynski, an anarchist and assistant professor at the Concordia University's School of Community and Public Affairs, concluded:

"This experience, in the wake of the Occupy movement, shows that this type of social awakening served as a platform for meetings and discussions amongst neighbors. Many amazing things emerged out of these assemblies. But as with any prefigurative attempt at direct democracy, tensions emerged when participants attempted to agree on a common platform. Deliberation was long, sometimes tedious, scaring certain participants away. It is always easier to agree on what we are against, than on the solutions we propose!"

Van Caloen, from the same district, voiced a belief that participants who concentrated on solving current problems — like the fee hike — were not motivated to engage in discussions about how to create broader, new visions for society. And in the case of last year's protests, he said, many people did not understand the role that the direct democratic process itself played.Thus, from the Maple Spring we can observe two kinds of mobilization and strategies: on the one hand, engaging with the state by protesting, and on the other hand developing democratic processes from below to imagine a system without the current power relations. The latter tactic was described by David Graeber as characteristic to the Occupy movement, which did not formulate concrete policy demands and has not explicitly engaged with the current system.

These two logics of action correspond to the distinction, drawn by Marina Sitrin, between social movements focused either on taking influence (power over) or creating autonomy of society through establishing relations within a group (power with). According to Richard J. F. Day, the newest generation of social movements is against any hegemonic solutions, ie. the reformist strategy to impose laws and policies of the state.

The student movement in Quebec has developed from a long tradition of anti-authoritarian mobilizations and embraced the principles of direct democracy. It is as a new type of movement stressing horizontalism and the absence of leaders. However, the demands in Quebec were very precise, namely the opposition to the student fees hikes and the demand for free education in the long run.

The tactics involved in the struggle brought limited results. The new government won thanks to the students' mobilization, but it has not kept its promises. Attempts to introduce direct democracy at the neighborhood level has ended with the exhaustion of the majority of participants, and the perseverance of small groups of activists. The advantage of these meetings is that people have become more connected for mobilizations in the future. And there are also some concrete examples that came out of the neighborhood assemblies.

Amy from Rosemont-Petite-Patrie reports that their assembly has been working on the organization of a collective kitchen in the neighborhood. Collective kitchens were started in the 1980s and constitute a part of Quebec's social welfare and culture; there are approximately 500 such kitchens in Montréal. The new kitchen in Rosemont-Petite-Patrie will collect part of its produce from dumpster diving to help achieve more financial autonomy for the activists.

Educational events have also been organized, like the education committee in Hochelaga-Maisonneuve which is considering starting a local towns-in-transition initiative, similarly to the Villeray district of Montréal. The advantage of these kinds of projects is that they address the financial autonomy of participants.

Instead of having abstract discussions on a more intellectual level, these assemblies are focused on energizing the movement and making it more accessible to people from a working class background. It is often observed that the Occupy movement consists mainly of white, middle-class people who found themselves in a similar situation as the working class. In the long run, exercising direct democracy projects on a small scale, and questioning current power relations by practicing counter-capitalist forms of production, may prepare a cultural base for a more encompassing change.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments