Two red dresses hang in a tree at Swan Creek Park on May 11, 2018, in Tacoma, Wash. The red dresses symbolize missing and murdered Indigenous women. - Photo: Jovelle Tamayo for The Intercept

Women on the Yakama Indian Reservation in Washington state didn’t have any particular term for the way the violent deaths and sudden disappearances of their sisters, mothers, friends, and neighbors had become woven into everyday life.

“I didn’t know, like many, that there was a title, that there was a word for it,” said Roxanne White, who is Yakama and Nez Perce and grew up on the reservation. White has become a leader in the movement to address the disproportionate rates of homicide and missing persons cases among American Indian women, but the first time she heard the term “missing and murdered Indigenous women” was less than two years ago, at a Dakota Access pipeline resistance camp at Standing Rock. There, she met women who had traveled from Canada to speak about disappearances in First Nations to the north, where Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s administration launched a historic national inquiry into the issue in 2016.

“I knew exactly what they were talking about,” White said. “I had survived all of this and witnessed all of this.” White’s aunt was murdered in 1996, and there were plenty of others in her orbit who had disappeared or died violently.

In the mid-2000s, the FBI re-examined 16 deaths in the vicinity of the Yakama reservation, mostly Native American women whose remains were found between 1980 and 1992 — so many deaths in such quick succession that many were convinced it must have been the work of a serial killer. As the mysterious deaths went unsolved, community members also became convinced of the FBI’s indifference.

In 2009, the agency released its findings; investigators had discovered no serial killer or any one culprit. Ten of the deaths were believed by the FBI to be homicides — women who had been shot, stabbed, beaten, or run over. Two of the deaths were classified as accidental drownings, one woman died of hypothermia, and in three cases, the cause of death was unknown. Media attention moved on after the anticlimactic results, although women on the reservation continued to disappear and die under suspicious circumstances.

Nearly 10 years later, a new law set to take effect in June will require the Washington State Patrol to determine just how many American Indian women have gone missing in the state. Working with tribes and the Department of Justice, the agency will use the data as part of a study to determine how to report and identify missing women.

The law’s sponsor was state Republican Rep. Gina Mosbrucker, whose district includes Yakama — Mosbrucker is a fifth-generation resident of Klickitat County, which includes the southern edge of the reservation. But Mosbrucker was compelled to act on the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women not in the wake of the murders on the reservation near her home, but after seeing the 2017 film “Wind River,” a fictional account of the murder of a young woman found frozen in the snow on a reservation in Wyoming. “The more I looked into it, and the more I spoke to tribal members living in Washington, I realized this isn’t just some Hollywood storyline,” Mosbrucker said.

“There’s a little bit of justice in the acknowledgement that there’s an injustice,” said Carolyn DeFord, whose mother, Leona LeClair Kinsey, a member of the Puyallup Tribe, disappeared 18 years ago. “It’s a slow boat to turn around, because it’s a 500-year-old problem.”

For the first time, the U.S. government is taking steps toward addressing a problem that until recently went unnamed. The Washington law is among a handful of recent legislative efforts, including proposed legislation in Minnesota and a federal bill known as Savanna’s Act, that seek to ramp up data collection around missing Indigenous persons and improve protocols for investigations of crimes on reservation land.

But if Canada provides any clues, the road ahead will be steep for organizers and families who are pushing for an end to the violence and neglect. There, many families have rescinded their support for the inquiry launched by Trudeau, arguing that it has been mismanaged and re-traumatizing for families and has followed a colonial model that excludes the grassroots.

Organizers argue that any chances of success lie in the government’s willingness to follow the lead of communities most impacted. As Annita Lucchesi, a Southern Cheyenne cartographer who is building a database of missing and murdered Indigenous women, put it, “I don’t think you can fix problems that have been created by poor legislation with more legislation rooted in the same way of knowing and in the same culture.”

Data Reveals Indifference

Lucchesi’s database includes cases in the U.S. and Canada going back to 1900, relying on news reports, law enforcement data, government missing persons databases, and information shared by Indigenous families and community members. So far, her data set includes 2,501 cases, and it’s far from complete.

Behind the vanishing women is an array of causes — domestic violence and sex trafficking, as well as police indifference, racism, lack of resources allocated to tribal governments, and complex jurisdictional issues between tribal, federal, and local law enforcement that slow down investigations in their crucial first days and make it easier for non-Indigenous people to get away with violent crime. For most criminal cases, tribal courts lack the ability to prosecute perpetrators who are not tribal members. Although the 2013 Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act allowed tribal courts to pursue domestic violence cases committed by non-Native people, not all tribes exercise that jurisdiction, and many other types of physical and sexual violence are not covered by the exception.

Lucchesi is building her database because no government entity has undertaken such an effort. As demonstrated in an investigative seriesby Reveal, data collection on missing persons is terrible in the U.S. — the central repository for information, the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, or NamUs, contains data that’s submitted only voluntarily by law enforcement and is thus incomplete. When it comes to Indigenous women, the problem is exacerbated by confusing jurisdictional issues on reservation land, where it’s often unclear which agencies have responsibility to look for a missing person or submit their information to the database.

Data about those who have been murdered is also sparse — it’s been less than a priority for U.S. police to track homicide rates of Indigenous women, if the convoluted responses to Lucchesi’s requests for historical data are any indication.

But the data that does exist provides a window into the scope of the violence and its impact on Indigenous women’s lives. According to the results of the 2010 National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, 84 percent of Indigenous women interviewed had experienced violence in their life; 56 percent had experienced sexual violence. According to data collected between 1992 and 2001, American Indians were twice as likely as any other racial group to be raped or sexually assaulted. A study of American Indian causes of death between 1999 and 2009 found Indigenous women had a homicide rate three times that of white women. And an analysis of data collected between 1994 and 1998 showed that some counties had murder rates of American Indian women that were more than 10 times the national average. Much of this data is limited by the willingness of individuals to report violence to police and of law enforcement to designate deaths as homicide.

Improving the data is a key objective of the proposed laws. The most significant piece of legislation so far is Savanna’s Act, introduced in October 2017 by U.S. Sen. Heidi Heitkamp, a Democrat from North Dakota. The act is named for Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind, a 22-year-old member of the Spirit Lake tribe who was eight months pregnant when she disappeared from her home in Fargo in August 2017. Her body was found a week later in the Red River. She had been murdered by neighbors who kidnapped her newborn.

The law would see tribal affiliation added to federal databases, including NamUS; the National Crime Information Center (the FBI’s primary data collection system); and other databases that aggregate fingerprints and DNA. It would force the U.S. attorney general to develop a plan for making those databases more accessible to tribal governments and require the Department of Justice to develop a standard protocol for investigating cases of missing and murdered Indigenous people. The government would also be required to submit an annual report with statistics about missing and murdered Indigenous women and recommendations for improving the data. Heitkamp is currently working on building support for the bill.

Additional federal legislation would provide grants for victims services in tribal communities, collect better data on American Indian human trafficking victims, and improve access to the AMBER alert system in Indian country.

In Minnesota, legislation to create a task force on missing and murdered Indigenous women was introduced on March 1. The bill asks the task force to uncover the “underlying historical, social, economic, institutional, and cultural factors” behind the violence and provide recommendations on how to better track missing Indigenous women, prevent violence against them, and support healing from trauma.

The legislation was pushed forward by two Indigenous lawmakers. One of them, state Rep. Jamie Becker-Finn, who grew up on the Leech Lake Reservation, has described how her great-grandmother disappeared back in 1931. Although her body was later discovered, how she died has never been determined.

Everybody Knows Somebody

After her mother disappeared, Carolyn DeFord, who was raising her three young children paycheck to paycheck at the time, found a void of support and information. Her mom lived in the small town of La Grande, Oregon, and had struggled with addiction for a couple of years. DeFord felt that police didn’t move quickly to find her because they knew her history. DeFord recalled an officer with the La Grande Police Department reminding her that it was not illegal for an adult to disappear — it was implied that her mother might be out partying. But DeFord knew her mother would never have left her beloved dog locked in the house; something severe had happened. Nearly two decades later, DeFord’s mother has not reappeared.

As time went on, DeFord began reaching out to other women whose family members had gone missing. She manages a Facebook pagethat features photos of missing persons and the details of their cases. When she travels, she brings a stack of posters “of somebody who’s in my mind that day. I don’t necessarily pick or choose. Whoever I’m feeling, I put out there,” she said. The stories she’s heard from others are familiar: investigations delayed because of assumptions about the lifestyle of the missing person — or about Indigenous people more broadly; lack of clarity around which agency should be searching; little support for families grappling with trauma; and an overwhelming sense of erasure.

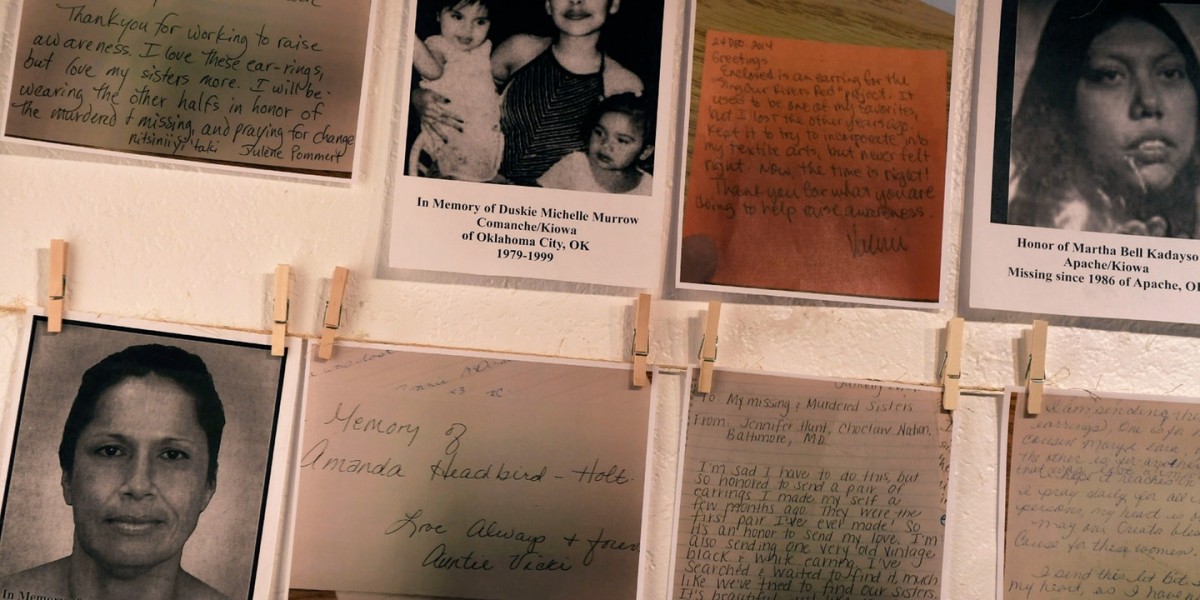

The growing movement around missing and murdered Indigenous women didn’t arise out of data — it came from the fact that so many Indigenous women know someone who has died violently or disappeared. One of the hallmarks of the movement is that it does not center around how the woman was murdered or who killed her. It identifies the generations-long elimination of thousands of women from Indigenous communities as a direct result of government attempts to eliminate Indigenous cultures.

Recent legislative efforts at addressing the complex matrix of issues behind the violence only begin to acknowledge that long history. Already, Lucchesi and other advocates say the new legislation in Washington overlooks some of the root causes of the unsolved disappearances. In particular, Lucchesi points to the fact that it is the Washington State Patrol that will conduct the state’s study.

“They’re probably not the best agency to do it,” she said. “That’s already a fraught relationship there.” The Yakama Nation Tribal Council, for example, recently passed a resolution declaring a public safety crisis on the reservation, noting that the crisis can be traced in part to the state patrol’s “refusal to actively patrol” Washington’s public rights of way that fall within reservation boundaries.

“That’s an unfortunate replication of the [Canadian] inquiry — to rely on Western legal framework,” said Lucchesi. “There’s quite a few families who don’t feel comfortable talking to law enforcement, that would feel more comfortable coming forward and sharing these stories if it was someone from their own community.”

Canada’s Inquiry Leaves Families Disillusioned

When Maggie Cywink was grappling with the 1994 murder of her sister Sonya Nadine, women were only beginning to hold marches in Canada to draw attention to their disappeared friends and relatives.

Cywink shared her story with Amnesty International, which published a groundbreaking report in 2004, titled “Stolen Sisters: A Human Rights Response to Discrimination and Violence Against Indigenous Women in Canada.” Three years later, serial killer Robert Pickton was sentenced to life imprisonment after the remains of 33 women — including a number of Indigenous women and sex workers — were found on his pig farm. An inquiry carried out between 2010 and 2012 found that because of who the women were, “police investigations into the missing and murdered women were blatant failures.” Meanwhile, organizing around the issue was intensifying — the Indigenous Idle No More movement made missing and murdered Indigenous women a central issue in its high-profile actions that began in 2012.

Momentum only continued to build. In 2014, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police released its estimate of Canada’s missing and murdered Indigenous women: 1,181 between 1980 and 2012, which some have argued is a significant undercount. Then, in 2015, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission released its findings. The commission was the result of a class-action lawsuit brought by survivors of Canada’s residential schools, which were rife with abuse and served as a key part of the country’s assimilation attempts, tearing children from their families and cultures. One of the commission’s recommendations was that a missing and murdered Indigenous women inquiry should be launched.

“Then the Liberal government made the national inquiry a campaign promise,” said Cywink. “It went from something that was personal, that was grassroots, that was family, to something that became a political thing.”

As prime minister, Trudeau has promised a “total renewal” of relations with Indigenous Canadians and announced the launch of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, which also includes transgender, two-spirit, and nonbinary people as part of its mandate.

“We all felt a sense of relief. We all felt a sense of validation, that thank god this government is actually paying attention — helping us carry this burden we’ve been carrying all these generations. Maybe a little bit of our guard was let down,” said Sheila North Wilson, grand chief of Manitoba’s Keewatinowi Okimakanak organization.

Many families and advocates quickly became disillusioned, as commissioners were chosen with little input from longtime organizers. “We are deeply concerned and confused as to why so many of the most renowned family leaders, advocates, activists, and grassroots (in short, those known and respected across the country with a deep subject matter expertise), have not been asked to help,” wrote Cywink and more than 50 other advocates and family members in a letter to Chief Commissioner Marion Buller in May 2017.

Soon afterward, a commissioner and multiple staffers quit — the inquiry seemed to be in disarray. In another letter addressed to Trudeau, more than 140 signatories called for a “hard reset” of the inquiry, including the replacement of Buller, a member of the Mistawasis First Nation and British Columbia’s first Indigenous Provincial Court judge, who was described in the letter as sidelining family members rather than including their voices as central to the process.

But the inquiry continued, with commissioners touring the nation, offering families space to publicly share their missing or murdered relatives’ stories. Cywink was disturbed by the lack of trauma care offered by the commission, and she didn’t think it was clear what the stories would even be used for. She decided not to submit the story of her sister.

When the commissioners finished their tour last month, they requested an additional two years to complete their ambitious goal: to build a foundation from which Indigenous women could reclaim their power and place and ultimately end cycles of violence rooted in Canada’s foundations as a nation. Some critics of the inquiry, such as the Native Women’s Association of Canada, have come out in support of an extension (which so far has not been granted).

But Cywink and other organizers felt that the commission’s time was up. “You’ve had testimony from over 1,000 people. That should be plenty,” Cywink explained in an interview with The Intercept. “Write your report and be done with it. Then we’ll take all the recommendations that you give us, plus the thousands that we’ve already got, and we’ll ask the government for more money, then we’ll start to implement them.”

“The national inquiry has bulldozed through our communities and with an extension will continue to exacerbate the emotional and psychological burden on the very people it is intended to solace,” Cywink, North Wilson, and around 200 families and leaders wrote in another letter on April 11. “A recurring narrative from communities has emerged: They came, they took stories, they left.”

“Caught between the inquiry’s dysfunction and government inaction, Canadians remain immobilized voyeurs and consumers of horrific stories of missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, trans and two spirit people.”

After decades, the signatories were ready to be done proving the issue exists.

“We Have to Be the Ones to Demand Justice”

Amanda Takes War Bonnet, a public education specialist for the Native Women’s Society of the Great Plains, pointed out that what happened in Canada is unlikely to happen the same way in the U.S. — at least not anytime soon. She works in South Dakota, where legislators passed a law in 2010 meant to prevent Native communities from holding the churches that ran American Indian boarding schools accountable for sexual assault.

For now, in a country where so little has been done to account for 500 years of colonization and genocide, she takes heart from legislative efforts by politicians like Heitkamp — even if they’ve missed some of the root causes of the issue. She acknowledged that Heitkamp’s support for the oil industry in some ways conflicts with her work on human trafficking and missing and murdered Indigenous women. (The Trudeau administration, too, has been blasted by leaders of Canadian First Nations for agreeing this week to purchase the highly controversial Trans Mountain Pipeline for $4.5 billion, after pipeline owner Kinder Morgan threatened to drop the project. Several First Nations have been fighting in court to stop the project and leaders have called the purchase a betrayal of the reconciliation process.)

Heitkamp played a key role in ending the crude oil export ban, opening up the Bakken oil region to new markets overseas. On Heitkamp’s press releases about Savanna’s Law, she noted her previous efforts to address violence against Indigenous women, including pushing for the opening of an FBI field office on tribal land after the oil boom brought an influx of drugs, sex trafficking, and other crime.

“She’s a politician, so you’ve got to ride the fence, and you’ve got to do both things,” said Takes War Bonnet. She feels the federal legislation is a crucial first step for the U.S. government. “It’s really important work that she’s doing, because it helps set precedent.”

On May 5, communities across the U.S. held gatherings in acknowledgement of a newly designated National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Native Women and Girls. Roxanne White led a march of tribal members dressed in red through the Yakama reservation town of Toppenish, Washington. She asked marchers for the names of women and men who were gone. “I had so many people telling me this name, this name, all at once,” White said. White estimates she called out 30 names.

“We’re the only ones that are going to speak for them. It’s not going to be the president or the governor,” White said. “We have to be the ones to come out and demand justice, demand the police, when somebody goes missing, to do their damn job, hold them accountable.”

Originally published by The Intercept