The 2008 financial crash may been the biggest in world history. As with many financial meltdowns, it involved a market panic, a plunge in asset prices and a wave of risk aversion that prompted a severe recession, during which countless people lost their jobs, houses and health insurance (this was pre-Obamacare, mind you).

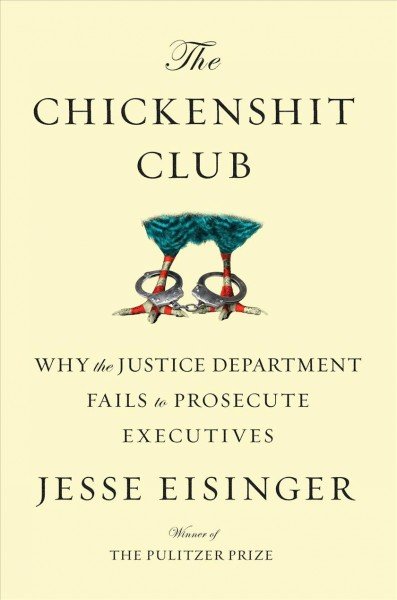

So much for the injury, now for the insult: No top banker went to jail or was in any way held accountable for the crash. As ProPublica reporter Jesse Eisinger writes in his new book, The Chickenshit Club: Why the Justice Department Fails to Prosecute Executives, that was no accident. It’s what you get when veneration of Wall Street meets a justice system that has learned to keep its head down, partly for fear of what failed prosecutions might do to elite legal careers.

The book's title refers to then-U.S. Attorney James Comey’s dismissive term for overly cautious prosecutors who’ve never lost a case. In the first decade of this century federal prosecutors were still capable of jailing key figures in the Enron, WorldCom and other scandals. So why such impunity following the subprime meltdown? Because, as Mr. Eisinger writes, the Department of Justice “has lost the will and indeed the ability to go after highest-ranking corporate wrongdoers.”

What Chickenshit describes is a colossal moral failure that comprises at least two strands: The revolving-door relationships between the DOJ and the private law firms that defend corporations, and the rise of negotiated settlements (known by the legal euphemism “deferred prosecution”) as a painless means of making amends. In the decade before 2002, Mr. Eisinger notes, federal prosecutors struck 18 such agreements; between 2002 and the fall of 2016 there were 419. This does not bode well for the next meltdown.

Occupy.com spoke recently with Mr. Eisinger. The following is an edited transcript of that conversation:

Chris Gay: I was intrigued to see that you mentioned the 1971 Powell Memo as a kind of starting point for the anti-statist, pro-business movement that seemed to culminate with Ronald Reagan. To what extent is the weak response to the executives in your book the result of the orchestrated, rightward political shift that followed?

Jesse Eisinger: It’s certainly a significant factor that has affected white-collar prosecutions. I wouldn’t say it was the only factor, and I’m not even sure it was part of a conscious effort, as opposed to a welcome byproduct, of the larger movement. We know from the Powell Memo and from many accounts of the rise of the conservative movement that there was a concerted effort to influence policymaking through think tanks, academia – it was essentially the playbook that the Powell Memo outlined. The Powell Memo doesn’t say anything, as I recall, about white-collar criminality, but the rise of libertarian judges has made the courts much more sympathetic to white-collar defendants.

CG: Is there a single character who you think exemplifies the willful negligence of the institutions that over-leveraged and fueled the crisis, or a single prosecutor most responsible for the weak response?

JE: Well, I go through [AIG executive Joseph] Cassano in my book and why prosecutors thought he should be prosecuted. He’s certainly somebody I thought probably should have been prosecuted. My argument is that [prosecutors] didn’t really look, not that they were sitting on clear evidence that there were specific crimes committed by sophisticated executives.

But that wasn’t really the aim of the book. It’s not a legal brief to lay out specific guilt or to try to prosecute a case against a specific executive. In fact, I avoided that because I didn’t want to get into legal arcana about, Is this guy really guilty? I think [Countrywide CEO] Angelo Mozilo was certainly a serious candidate for investigation and possibly indictment. I think there were dozens of bankers who should have been indicted for financial activities, but I really didn’t want to get distracted by making one case.

CG: Is underfunding of regulators an obstacle to pursuing cases, and if so, is it intended to impede white-collar prosecutions?

JE: I don’t think that’s the issue. I think small groups of able prosecutors could bring a lot of cases and do a lot of good. I do think that prosecutors should be paid a lot more money, like triple their salary. I think we should pay them $400,000, $450,000 instead of $150,000, because I think it would attract a better group of people who would stay longer and be less interested in going to criminal-defense firms. But I don’t think that resources are really the issue. I think it’s the approach and the will and the revolving door here that’s really the issue.

CG: Is there any evidence of reforms in the pipeline, either legislative or regulatory, that would make white-collar prosecutions more likely?

JE: No, I don’t think so. There have been financial reforms and I think they’ve made the financial system safer, but not safe enough. But in terms of white-collar criminal reform, no there haven’t been. I don’t think the problem has been officially recognized by the Justice Department. They haven’t analyzed what the approach is, what their tools are, [the cases] they’ve lost.

As critical as I am of the Obama administration in the book, I think the Sessions DOJ is going to be an order of magnitude worse. I think the best-case scenario is that they neglect white-collar prosecutions, and the worst case is that they start to use prosecutions as a stick to attack their enemies and reward their friends. So I think that things can get a lot worse.

CG: Are attempts to repeal Dodd-Frank, though they seem to have failed for now, a threat? Is the Trump administration already doing things that will incentivize future abuses and make prosecutions less likely?

JE: I think Dodd-Frank is not that strong, but it’s certainly stronger than if it got repealed. I think [the administration] is signaling that the punch bowl is back, and they’re signaling to regulators that they’re looking the other way. And as a byproduct we’re going to have a lot of white-collar crime. The problem is that we’re not going to see it for a few years. It’s very hard to discern right now, but it’s coming.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments