Photo: Der Spiegel

Most analysts and citizens of Western society suppose that we live in a democracy.

But is it really democracy - a system where the people rule and its representatives execute the popular will? Or, do we live in an oligarchy disguised as democracy? Oligarchy: in others words, a system where a small, inner circle, takes the decisions they feel necessary.

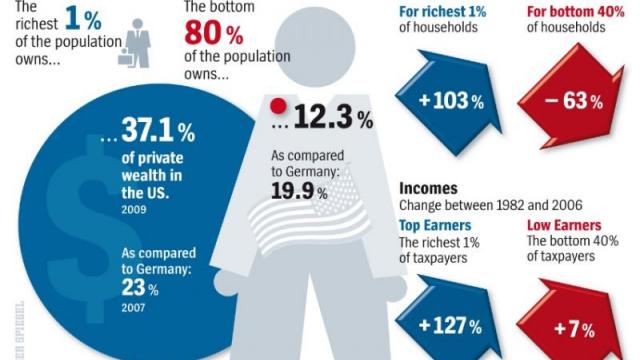

Capitalism turned a corner in 1980. Since then, inequality has not ceased to rise in all Western countries, after several decades during which income distribution remained relatively stable. At the same time, there has been a second phenomenon at the core of rising inequality: the very rich have expanded their share of revenue faster than the “merely” rich. So, at the summit of society, a very coherent group has emerged that pursues a rationale of its own, in terms of power as well as lifestyle.

The collapse of the financial system that began in 2007 revealed the new strength of the oligarchic class. Logic would seem to dictate that those responsible for the debacle should be sanctioned and the financial system reformed. Instead, they hang on to their power and communicate their decisions to the politicians concerned, who, in turn, implement these decisions without flinching because they are just the visible front of a systematic intermingling of public policy with private enterprise.

In a democracy, there is a fundamental cleavage between the public sector, concerned with the general interest, and the private sector and its concern for private interests, which remain rightful as long as these private interests do not jeopardize the common good. But in an oligarchy, the cleavage is horizontal, between those at the top of the pyramid, who provide direction in their different specific fields, and the body politic, conditioned to consider this cleavage legitimate or inevitable.

In an oligarchy, success notably means the orderly control of the State. The word “orderly” is important here: There is no question of ruining the State, as in an African dictatorship where too violent extraction of resources keeps the people down and impoverished; rather, it means “orderly” extraction of resources, without annihilating the body politic and without unleashing a rebellion that could threaten the durability of the process of extraction. An adequate level of deduction and the form that it takes attest to the savoir-faire of the oligarchy, which varies according to the country, its national culture and its history.

Actual deduction is first revealed by two movements that have oriented capitalism over the last 30 years: the weight of large financial companies, which has become huge, relative to the States, and the ideology of privatization, which facilitates the transfer of public funds into the coffers of the oligarchy.

Economic globalization has become a movement of continuous concentration. Numerous industrial sectors thus have become the private preserves of the oligopoly. Nevertheless, the global power of companies should not be exaggerated: in 2002, the 50 largest industrial and service companies represented only 4.5% of the GDP of the 50 largest countries.

But a new factor has profoundly modified the economic scene: banks, pension funds and asset management companies have seen their overall size increase and largely overtake that of large enterprises. In 2002, the top 100 companies in the world together represented $5.6 billion; midgets compared with the top 100 banks, which together managed $29.6 billion in assets. The power of the financial sector has become colossal. In 2010, the ten largest global banks each reported assets of more than 2 trillion Euros when the GDP of a medium-sized country like Greece is on the order of 200 billion Euros.

The interests of the financial community have taken over economic policy, notably by the regular transition of bankers to positions of political policy-making, with the most spectacular but certainly not isolated example being the numerous Goldman Sachs associates who have moved to public office. The second aspect of oligarchic control of the public sector is the general movement toward privatization that began in the 1980s. After having turned industrial enterprises over to private interests, oligarchic governments went after services (transportation, electricity, telecommunications, gaming), then health, education and the military.

Oligarchic regimes carefully preserve the principle of elected legislative assemblies. But to keep these assemblies from orienting their remaining prerogatives in the wrong direction, there is “lobbying,” or discreet influence on elected officials and policy-makers by trade groups or industries united by a specific common interest.

Every sector — finance, oil, computers, electricity, chemicals, transport, agri-business — makes impressive efforts to influence lawmakers in Washington, Brussels and elsewhere. The success that they obtain is remarkable. For example, the proliferation of genetically modified organisms in the United States would not have been as spectacular as it has been without the close ties between industry and successive governments. European projects to regulate the financial sector are entrusted to groups of experts essentially composed of representatives ...of the financial sector.

The political system of the United States stands out for another reason: electoral victories cost millions. Candidates cannot win elections unless they can spend more than their opponents on television ads and other publicity. Of the Representatives and Senators elected to Congress in November 2008, 93% had spent the most money during their respective campaigns. In the House and the Senate, those elected will defend the interests of their donors rather than their constituents. The wealthiest win: elections and oligarchy hand in hand.

Why don’t we rebel?

The ease with which the oligarchic regime absorbed the financial crisis that began in 2007 is disconcerting. Rescue of the financial system has revealed more clearly than ever the vital importance of public intervention, thereby clearly demonstrating the inanity of free-market dogma, along with the cynicism and incompetence of “financial champions” and other “experts” who were incapable of predicting catastrophe. People in the West nevertheless have continued to accept, without much outcry, rising unemployment, proliferating poverty and stratospheric inequality, not to mention the implacable destruction of ecology.

How to explain this popular apathy? One of the causes is mental and political conditioning by the media, specifically, television. The young are the first victims: ingesting one hundred thousand advertising messages since birth does not lead to the development of a global political consciousness. Predicting the inevitable prolongation of media conditioning is fatalistic fatalism. The “there is no alternative” of Margaret Thatcher is durably embedded in the collective mind: there is no alternative to capitalism, since communism has been overcome; growth is indispensable, otherwise employment will rise even more; the hyper-rich cannot be taxed or they will flee elsewhere; whatever we do for the environment will be wiped out by the weight of China, etc.

Such fatalism is even more intense in that it turns a deaf ear to a culture that has become massively individualistic. Since 1980, to a degree never before seen, capitalism has generalized withdrawal from the group, denial of the collective, scorn for cooperation, ostentatious competition.

But oligarchic societies are not dictatorships, looming over fearful shadows. If people do not rebel, it is also because they do want to.

Cornelius Castoriadis once observed that there is “one elementary truth that will seem very disagreeable to some: the system prevails because it has succeeded in creating popular adhesion to what exists”. Capitalist culture has placed “economic ‘needs’ at the centre of everything”, and “capitalism satisfies these needs that it has created as-well-as-it-can-most-of-the time.” In the 1960s, Herbert Marcuse too underlined the disappearance of opposition between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie as soon as “a relatively satisfied middle class replaces the poor working class”. While it has clearly and increasingly weakened the middle class in the West, the shock of 2007 and after has not yet inspired feelings of revolt or solidarity with the neediest. Life is still pretty comfortable. Fear is what dominates: loss of status threatens, while the value system of society, directed by the rivalry of ostentation, stigmatizes anything that looks like failure. Individual strategies of protection therefore dominate the behavior of the middle class.

Finally, members of this class absorb the discovery that, in spite of their difficulties, they are some of the richest on the planet. Evidence of planet-wide inequality finally strikes everybody, and members of Western society, even those duped by the oligarchy, realize that they are privileged, which creates paradoxical solidarity with the ruling class and cynically contributes to generalized vulnerability.

What does globalization really mean?

As a whole, society today is organized to attribute the largest part of production possible to the product of the collective activity of a small number of people who run the society. These people declare that economic prosperity is the key to everything, and that growth, combined with technology, will resolve problems, which is hard to deny.

This would be of secondary historic importance if it did not come up against the dominant phenomenon of our time: an ecological crisis that corresponds to a decisive moment in the history of humanity, a time when the limits of the biosphere are reached. In 30 years, the rhythm of destruction has accelerated, and that which seemed to be the opinion of unorthodox doomsayers has come to form the basis of a pessimistic collective conscience. This movement of ideas represents a radical upheaval of historical perspective: while the emancipation of the Age of Enlightenment was energized by the promise of a better future, the dawn of the third millennium only sheds an uncertain light on a world where the main objective has become to avoid its destruction.

And yet, the last 30 years have seen a number of countries in the South grow very rapidly. A group of emerging countries is acquiring enough weight to dominate the global economy. This development, has, in 20 years, reduced by one quarter the number of people living on less than a dollar a day. But a billion and a half humans are still destitute, while the average income of the countries in the Southern portion of the planet remains far below that of rich countries. And yet, aggravated by intensified growth in these countries, the ecological crisis becomes an obstacle for them to overcome. It is highly improbable that they ever will reach the level of prosperity of the inhabitants of the North. This inequality does not seem to be justifiable or lasting. What is really at stake is the end of the Western exception. The industrial revolution that began in Europe, and then spread to the United States and Japan, opened a parenthesis during which Western countries significantly separated, in terms of wealth and power, from the rest of the world. This separation reached its peak at the beginning of the 21st century, and now, we are beginning to see it shrink.

The gap cannot be closed simply by coming up from the bottom. Because of ecological limitations, not all inhabitants of the planet can live like people in the United States, Europe or Japan. Reduction of the wealth gap must come, therefore, from a significant lowering from the top. Against all prevailing current debate, biospheric policy shows the way: Westerners must reduce their material consumption and their consumption of energy, in order to leave room for their companions on this planet to consume more. The material impoverishment of Westerners is the new horizon of global policy.

This means that we must reclaim democracy in a mental context that is radically different from the one in which it has developed. In the 19th and 20th centuries, democracy grew and won converts because it promised improvement of the lot of the greatest number, and it has lived up to the promise, in association with capitalism. Today, capitalism has deserted democracy, and we must reinvigorate democracy by espousing a well-being, a “well-living”, that is fundamentally different from that which today makes advertising shine… which, first of all, would prevent the decline of society into chaos… which, then, would no longer be based on the attraction of objects, but , rather, on moderation leavened by renewed ties to society. We must invent a democracy with no growth.

The question does not only concern Western societies. What is the dividing line in the world of today? That which opposes the “North” and the “South” or rather the gap that separates the global oligarchy from the people that it subjugates? Countries in the South are much less homogeneous than the image of them provided by media mesmerized by economic performance: they are living through major conflicts having to do with the distribution of the riches of production, mostly to the benefit of an avid oligarchy, and on a development model that skirts the agricultural question and concern for the environment. There often is opposition between a governing class — which relies on urban classes that enjoy a rising standard of living — and farmers, the proletariat and slumdwellers. What’s more, oligarchies in all the world’s countries close ranks: they form a cross-border class with a shared ideology and common interests. Countries of the South should not be considered as a bloc. In so-called emerging countries, part of the middle class and the rich enjoy a standard of living with an ecological impact that is as significant as that of lifestyle in the West. Global inequality of course remains a phenomenon that must be taken into consideration when it comes to the rebalancing required between the parts of the world where ecological constraint is needed.

But it masks major inequality at the core of all societies. To be crystal clear: no little employee in Europe will accept a lower standard of living if Chinese millionaires are the ones who benefit. To meet the ecological challenge and avoid the nationalistic retreat that would result from a country-by-country or bloc-by-bloc approach to the problem, it is vital to generate international solidarity among people, in order, to impose, everywhere, the reduction of inequality. This means that the democratic stakes are planet-wide: human rights, freedom of expression, shared decision-making are not Western values but the means by which people free themselves from their oppressors.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments