Protests against the dire state of American policing are working.

After the 2014 rise of Black Lives Matter protests over police shootings and brutality, states have passed more and more laws changing how their police departments work. In total, a new report by the policy and research group Vera Institute of Justice found that 34 states and Washington, DC, passed at least 79 laws regarding police in 2015 and 2016 — compared to fewer than 20 bills in the three-year period before.

The reforms widely varied: limiting use of force, prohibiting racial profiling, dictating the implementation of body cameras, improving accountability in cases of police misconduct, and more. Some states also passed increased protections for police, such as a “Blue Alert” system that delivers “coordinated public notifications to aid in the timely identification, location, and apprehension of an individual suspected of killing or seriously wounding a law enforcement officer,” according to Vera.

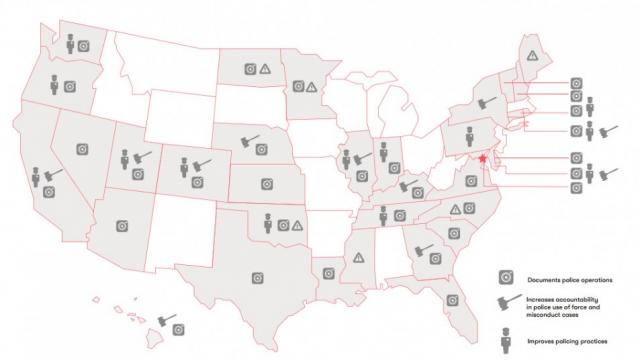

Vera broke down the reforms into four categories: documenting police operations, increasing accountability, improving policing practices, and increasing protections for police. Then they mapped out the legislation.

You can read Vera’s full report to see every single law on the map, but here is a small sampling of the kinds of things states have done, taken from Vera’s report:

• In 2015, Connecticut passed HB 7103 to, among other things, require that police training programs better cover the use of force, cultural sensitivity, and bias-free policing, and require the Division of Criminal Justice, with the help of a special or independent prosecutor, to investigate police use of force that results in death. • In 2015, Illinois passed SB 1304 to prohibit the use of chokeholds by police. • In 2015, Delaware passed HCR 46 to encourage police departments to establish body camera policies. • In 2016, Washington state passed HB 2908 to create a joint legislative task force that will review use of force practices nationwide to propose changes that will hopefully reduce the number of deadly encounters between police and civilians. • In 2016, Colorado passed HB 1263 to prohibit police officers from profiling solely based on race, ethnicity, gender, national origin, language, religion, sexual orientation, gender identity, age, or disability. • In 2016, Oklahoma passed SB 1202 to require police officers complete additional training every year that includes dealing with people with mental health conditions.

The list doesn’t account for local reform efforts, which can often account for even larger changes since city and county governments have more direct control over their police departments. But several municipalities have enacted reforms, such as in 2015 when the Chicago City Council expanded the city’s prohibition on profiling to include national origin and gender identity and in 2016 when San Francisco voters gave more power to the city’s Office of Citizen Complaints so it investigates all incidents in which a police officer fires a weapon and causes injury or death.

Many of the changes, Vera noted, focused on improving police-community relations, typically by taking steps that show police are being held accountable. This is crucial not just for weeding out harmful police practices, but also for public safety: A major cause of crime — particularly in minority neighborhoods — is widespread distrust in the police, fostered by what residents see as both overpolicing for petty crimes, like loitering and traffic violations, and underpolicing for serious offenses, like shootings and murders.

As John Jay College criminal justice expert David Kennedy previously told me, “When communities don’t trust the police and are afraid of the police, then they will not and cannot work with police and within the law around issues in their own community. Then those issues within the community become issues the community needs to deal with on their own — and that leads to violence.”

Or as journalist Jill Leovy put it in her book Ghettoside, “Take a bunch of teenage boys from the whitest, safest suburb in America and plunk them down in a place where their friends are murdered and they are constantly attacked and threatened. Signal that no one cares, and fail to solve murders. Limit their options for escape. Then see what happens.”

The state and local efforts also offer a bright spot for those nervous about the Trump administration’s opposition to criminal justice reform: Even if the federal government does nothing, cities and states are clearly moving forward on changes.

Still, the reforms passed by cities and states so far obviously haven’t addressed every problem with policing in America. And it’s unclear just how successfully the reforms will be implemented and enforced. But they’re a start, showing that American policing really is changing after protests rose up in Ferguson, Missouri; Baltimore; Chicago; and many other cities across the country.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments