The Pacific Northwest has for years been a hot spot in the battle between the coal industry and environmentalists. While the fossil fuel sector has pinned hopes on the region as an export hub for coal it is finding increasingly difficult to burn at home, green activists have fiercely fought that idea at every step.

Last week that struggle took what could be a significant turn when the state of Oregon denied a crucial permit for a proposed export terminal that activists and some politicians say would wreak environmental havoc on the western part of the state.

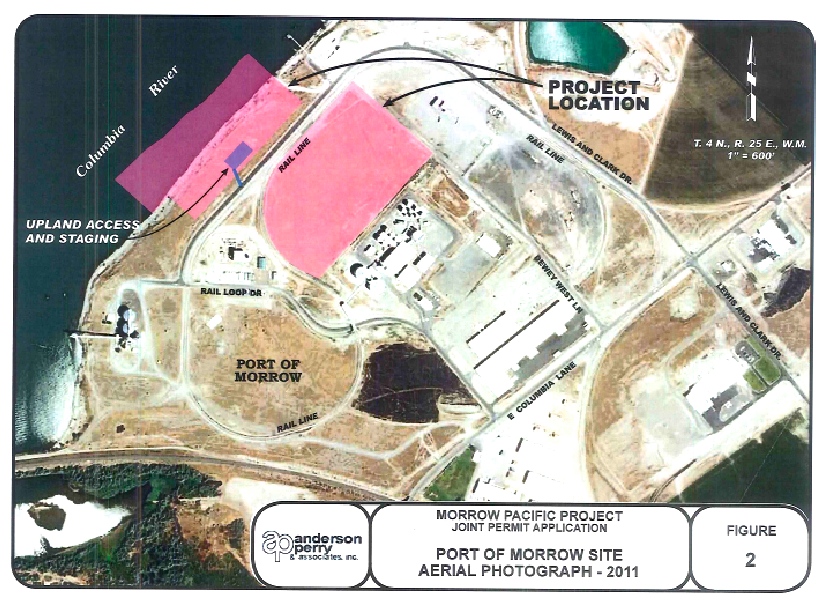

While the permit denial for the relatively small Morrow Pacific coal terminal is by no means the end of the fight in the region, it may be a sign of things to come for the coal industry.

As proposed environmental regulations for coal-fired power plants cause the coal industry to rethink its strategy in the U.S., companies have increasingly seen exports to burgeoning economies like South Korea, China and India as the answer to declining profits.

The most logical and profitable route for those exports is through terminals in California, Oregon, Washington and British Columbia. But a steady stream of activism and an unfavorable local political climate has often delayed the building of export terminals.

Environmentalists say the terminals would not only encourage CO2-emitting coal to be burned elsewhere but would pollute local waterways and increase rail and truck traffic in once restful regions. Now green activists may have the first sign that politicians in the Pacific Northwest agree.

“It’s a big push, and we’re all superthankful and hopeful, because we felt that all these tiny towns and bigger towns were powerless,” said Arlene Burns, president of the Mosier City Council. Mosier rests 90 miles downstream from where the proposed Morrow Pacific facility would be built on the Columbia River. “The fight’s not by any means over, but we’ve shown we can stand up together.”

"Not a Done Deal"

In its rejection of a key permit needed by Australian coal giant Ambre Energy to build the terminal, Oregon’s Department of State Lands (DSL) said last week that the project “would unreasonably interfere with the paramount policy of this state to preserve the use of its waters for navigation, fishing and public recreation.”

Ambre has 21 days to appeal the ruling, an action spokeswoman Liz Fuller said the company is considering. She called the decision politically motivated, saying the DSL caved in to environmentalists while ignoring those who supported the project.

“There’s been a lot of support of the project, but that doesn’t tend to be as loud as opposition,” she said.

The prospects for increased coal exports from the region have decreased in recent years. In 2012 there were at least six proposed projects in the works. That number now stands at three – two if the Morrow project is nixed.

Those two projects are much larger than Morrow, which would export about 8.8 million tons of coal annually. The Gateway Pacific project in Washington would export about 53 million tons a year, and the Millennium Bulk project, also in Washington, would export about 49 million tons annually.

The fact that the smallest of the three was denied a permit has given environmentalists hope that the larger projects will face similar opposition.

“It’s not a done deal, but it certainly poses some serious questions for those other, much larger facilities,” said Clark Williams-Derry, director of research at the Sightline Institute, an environmental think tank.

The coal industry has been struggling not only with environmental activism but also with declining reserves in the Appalachian region, fierce competition from abroad and a surging natural gas industry in the U.S.

Compounding those struggles is President Barack Obama and the Environmental Protection Agency, which issued draft regulations on carbon emissions this year that could drastically cut the viability of coal power plants in the U.S.

Because of those factors, it seemed one of the coal industry’s best options was to focus on mining from the Powder River Basin in Montana and shipping that via rail to the West Coast, where it could be exported to growing economic powerhouses in dire need of energy.

There are several other export terminals planned for California and Vancouver.

“This essentially just shifts the market,” said Williams-Derry. “The economics of it are broader than any one region.”

But even if those terminals are built, the U.S. coal industry might face an even more daunting challenge: declining demand elsewhere. In China and South Korea, two of the biggest markets for U.S. coal, the governments have been slowly shifting from their reliance on coal, as smog-covered cities make coal use less politically viable.

“There’s declining demand in China and strong activism here,” said Cesia Kearns, a campaigner with the Sierra Club in Oregon. “So it’s clear that exports are a rapidly closing window.”

*

MEANWHILE, Patrick Rucker and Nia Williams reported for Reuters that rail oil tankers which have fallen victim to U.S. safety rules are now also unwanted in Canada:

Thousands of oil train tankers soon to be deemed obsolete in the United States are unlikely to get a second life in Canada's oil sands industry, undercutting a U.S. government forecast that the costly cars will continue in use in the energy sector.

If thousands of obsolete tank cars are scrapped, it could add hundreds of millions of dollars to the cost of the proposal, industry officials said – unwelcome news for regulators trying to craft a safety plan that does not add crippling costs to industry.

Regulators on both sides of the border are contemplating rules to prevent oil train accidents like the July 2013 Lac Megantic disaster in Quebec, in which a runaway train loaded with fuel from North Dakota's Bakken oil patch derailed, killing 47 people.

Those plans would modernize the current U.S. fleet of roughly 90,000 tank cars with puncture-resistant shells and other costly upgrades that government and industry sources expect to cost more than $3 billion.

The U.S. Department of Transportation has said the transition will be eased with about 23,000 existing cars going into service to cart Canadian oil sands crude – a molasses-like fuel, bitumen, that is less flammable than ordinary crude oil.

"No cars will retire as a result of this rule," the DOT's Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) said in its oil train proposal released in July.

But industry experts said it is not feasible to simply retrofit the older cars to the specifications needed to carry oil sands, making it likely thousands of cars will be scrapped.

"We don't anticipate we will see the cars here," said Julie Puddell, investor relations manager of Keyera Corp, which operates a loading terminal in Edmonton, Alberta, with Kinder Morgan Energy Partners LP.

While the general purpose cars can be used to transport bitumen diluted with a light fuel called condensate, many oil sands shippers prefer speciality-built tank cars with internal heating coils, because heat stops the bitumen from solidifying while in transit and makes it easier to unload at refineries.

Industry sources say adding heated coils to a standard tank car - which can have a useful life of forty years or more - would have prohibitive costs.

"There are ways to retrofit, but it could make them even more expensive than a new-build," Puddell said.

A spokeswoman for Cenovus Energy Inc, Canada's No. 2 oil producer which aims to ship 30,000 barrels per day of oil by rail by year-end, said the company was focused on leasing new heated and coiled cars.

And Valero Energy Corp has ordered more than 2,900 heated tank cars for delivery in the next twelve months to take bitumen to its St. Charles, Louisiana refinery and elsewhere.

Between rail and barge deliveries, the largest U.S. independent oil refiner expects to be receiving more than 55,000 bpd of bitumen from Canada by mid-2015. A Valero spokesman said the company principally relies on heated cars to move the fuel.

A U.S. Transportation Department official said the agency's proposal was open to amendment following a public comment period that ends on Sept. 30.

"Regulators are academic when they write these rules. They always underestimate costs," said Larry Bierlein, a veteran hazardous materials lawyer and former hazmat counsel to the Department of Transportation.

"That will become clear as the industry digests this proposal and prepares for the political push-back," Bierlein said.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments